FEATURES

What it took to bring When The Wind Blows to film

by Ron Fleischer

Turning

When The Wind Blows, Raymond Briggs' famous illustrated book about

an elderly British couple dealing with the aftermath of a nuclear strike,

into an animated feature film was not going to be an easy task. Briggs' other

highly regarded children's story, The Snowman, had been very successfully

translated into an award-winning animated short, remaining true to its illustrated

style.

The classic, and conventional, Disney films, in which each animated drawing is traced and then painted onto a piece of celluloid (or cel), creates a "flat" result, more or less, even if tones, highlights and shadows are added. For The Snowman, the filmmakers wanted to retain the look of the original book's color pencil illustrations. This meant that the animators would have to forgo the cel process completely. Instead, each animated drawing (which lasted for 1/12th second) had to be fully rendered on a piece of registered illustration paper, and hand colored with different pencil shades.

Briggs wanted When The Wind Blows to have the same kind of illustrated look that The Snowman had. Unfortunately, to execute the same style for a feature film was out of the question; it would take too long and cost too much.

The filmmakers, however, did agree that When The Wind Blows deserved to have a unique look, one that would separate it from the mainstream animated features and stay true to the original book as well.

After Briggs' finalized the screenplay, the next step in making this feature would be creating a "storyboard." A storyboard displays each shot of the film as a small image, or series of images, showing all of the main action (and dialogue) in each shot. One of the next steps of a traditionally animated film would be to create the "layouts." These layouts are basically pencil drawings of each background that will eventually end up being the real thing (after the background painter does his job). Copies of each layout are put in each scene's folder, and used as a reference for the animator.

While

traditional layouts were done for all the scenes that took place outside of

the house where the old couple lived, the filmmakers did something a bit different

for the main setting of the film. Instead of creating layouts for the house's

interiors (and later painting fully rendered backgrounds), they constructed

a large model of the country dwelling, adding great detail to each room. Even

miniature props were built that interacted with the animated characters. A

phone, ironing board, radio, drain board and dishes, and blankets were perfectly

blended with the traditionally drawn animated characters.

Actually, two models of the house were constructed; one before the atomic blast, and the other after, displaying it's devastating results.

For all of the interior shots, a still photograph of one of the models was taken for each location that would represent a "layout" for a scene. In other words, instead of drawing a layout of the kitchen, where the couple would later be animated over, a photograph of the kitchen model, matching the storyboard angle, would be taken instead. These frames were then blown up and "pegged" in order to register with the animated sequence. This process was one of the many innovations that gave the film a unique look, and worked very well with the character animation.

There are a few other special shots that the filmmakers got from using the models. These shots usually appear at the beginning of a sequence, as many parts of the movie end by fading to black. In order to get a greater sense of perspective and movement "through" the house, a stop-motion technique was used for these shots. Stop-motion is the process where a physical object (like a puppet) is moved incrementally, being shot one frame at a time. Everything from Gumby to "Wallace and Gromit" are examples of stop-motion animation.

But, instead of animating a character or object, the camera itself became the animated subject. For instance, there is a great shot when Jim arrives home for the first time. He enters the house, walks through the hallway and into the kitchen where Hilda is waiting for him. The animators actually moved the rigged camera incrementally through the model, shooting a frame at a time as they went along. After the film was processed, each picture (or frame) was blown up and registered onto animation pegs. Instead of using one photo of the model for an animated sequence, the series of photos were changed for each frame along with the animated drawings. This created a really cool, yet subtle, effect that I'm sure most people don't even notice.

There

are a few brief sequences in the film that were created using the same time-consuming

process that was used for The Snowman. These special sequences ("Hilda's

Dream," "Wedding Sequence," and "Blitz Sequence") all had special animation

directors assigned to them. Each of these short sequences were created through

a series of highly rendered pencil drawings; sometimes shot traditionally

on 2's (2 frames per drawing, or 1/12th of a second), or shot through a series

of overlapping camera dissolves. The dissolves saved the animation from being

traditionally "in-betweened," which would have made these sequences much more

labor intensive. The series of dissolves between drawings still give the effect

of the piece being animated, without actually having to draw all the additional

illustrations. The effects of the nuclear blast are another beautifully rendered

sequence.

The same process can be seen in the animation that Scarfe created for The Wall. The beginning of "Empty Spaces," which features the extraordinary fornicating flowers, was done in this tediously illustrated style.

When The Wind Blows succeeded on many different levels, yet it still is quite a difficult film to watch. In my opinion, its greatest triumph was staying true to its original source, artistically and emotionally.

Ron Fleischer is an Animation Director with Startoons International, and is a staff writer for Spare Bricks.

A Floyd Fan's Intro to Cheap Trick

by Jacki Dimitroff

Circa

1977: just as utter boredom is about to strike me down dead, I get a call

from my friend Kevin. He tells me he's bought a new album and I have to get

over to his house right now to listen to it. While the CD rules today,

the medium lacks the anticipation and excitement of one sound: the crackle

of the stylus connecting to the vinyl of an album you've never heard before.

Circa

1977: just as utter boredom is about to strike me down dead, I get a call

from my friend Kevin. He tells me he's bought a new album and I have to get

over to his house right now to listen to it. While the CD rules today,

the medium lacks the anticipation and excitement of one sound: the crackle

of the stylus connecting to the vinyl of an album you've never heard before.

The album Kevin was so intent upon playing was Cheap Trick's debut album, Cheap Trick, and on that day, my musical identity cut its first tooth. Forget the big-hair styles of the rhythm and bass guitarists (styles which would later become the norm) and the quirky weirdness of the lead guitarist and the drummer. This band didn't need an image, because the music spoke for itself. It was blazing, rollicking, unabashedly pure rock and roll. It was fun.

Over 25 years later, I would discover Syd Barrett, and I found myself sharing the same laughing glee in his music (despite some pretty dour topics) that I originally found with Cheap Trick. Syd Barrett's rock and roll spirit that left him as he moved away from music found its way through the Yin and Yang to Cheap Trick's debut album.

Stylistically, Cheap Trick doesn't seem to compare to Barrett's music at all. Don't put in this first album expecting to hear acoustic ballads or electric guitar psychedelica. No, the music on Cheap Trick crashes through your speakers, bombarding you with a rumbling drumbeat and simplistic chord progressions. From the galloping beat of "Elo Kiddies" through the catchy, blues-influenced "Cry, Cry," Cheap Trick carries the sensation of motion from track to track. The music has a very heavy emphasis on the drums in almost every composition, unlike Barrett's songs. And don't look for too much innovation in the guitar work, either. While there are songs such as "The Ballad of TV Violence," and "Speak Now or Forever Hold Your Peace" that show some creative experimentation with an offbeat rhythm instead of a key-beat, standard rhythms generally prevail. This is basic garage band stuff, but it works very well. The guitar sound is rich and physical; and the melody re-mains consistent and doesn't get lost behind the hard drumbeat or sound ef-fects.

|

Cheap Trick rocks the Fillmore, 1998

|

On the other hand, the thematic content does compare to Barrett's music. For instance, in 1967 Syd Barrett's Pink Floyd sang a tune called "Arnold Layne," which was about a cross-dressing man with a panty fetish. In 1977, Cheap Trick offered up "Daddy Should Have Stayed in High School," a song about a middle-aged man with a Lolita complex. In both cases, the subject is a social outcast, and both songs also adopt a humorous approach to their subjects, as if to tell us to lighten up a bit.

The most surprising thematic similarity lies between Pink Floyd's "Jugband Blues" and Cheap Trick's "I Dig Go-Go Girls." The latter recording was not on the original release of Cheap Trick in 1977, but the marvels of modern technology have made this little-known gem available on the remaster. "Jugband Blues" displays the lost mind of Syd Barrett, who begins to understand his moving away from his band: "It's awfully considerate of you to think of me here / And I'm most obliged to you for making it clear / That I'm not here."

Similarly, "I Dig Go-Go Girls" depicts someone of a questionable moral character and concludes with the fol-lowing two lines: "Maybe I'm an idiot, maybe I'm crazy. Maybe I'm intelligent, maybe I'm a lunatic."

Both songs contain very powerful images of songwriters questioning themselves and their relationship with others. And Cheap Trick resurrecting the sanity theme is also a bit of irony. Even more, the musical climaxes are similar with Barrett choosing a chorus of unconventional kazoos, and Cheap Trick electing to sound like a Broadway stage production.

Five months after the release of Cheap Trick, the band released their second album In Color, and continued with the same raucous blend of standard guitar and heavy drums. When Heaven Tonight appeared in May of 1978, however, Cheap Trick finally seemed to break into the main stream with such songs as "Surrender" and the title track. And that is where my admiration for the band ended. Not because they suddenly became mainstream, but because their music suddenly sounded like it. Its hard to describe in words, but Cheap Trick seemed to lose that garage band edge that felt so right on the first two albums. Many Cheap Trick fans might disagree that the band lost its edge, but I think that very few could disagree that the sound changed at that time.

Almost 25 years between them, I consider my introductions to Cheap Trick and Syd Barrett as two of the most defining moments of my musical taste. Is it no wonder that I find similarities between the two? If you like Syd Barrett because of his ingenuity, his quirkiness and his ability to create musical im-agery, then I think you'll like Cheap Trick and In Color for their free-spirited rhythms and unabashed simplicity.

Jacki Dimitroff is a staff writer for Spare Bricks.

How Three Centuries of Colonialism Boiled Up into War in 1982

by Mike McInnis

If

you are anything at all like me, you had never heard of the Falkland Islands

before you got into Pink Floyd. And even if you had, you probably didn't realize

that the dispute behind the war that erupted between the United Kingdom and

Argentina in 1982, and which inspired Pink Floyd's The Final Cut album,

had been brewing for hundreds of years.

If

you are anything at all like me, you had never heard of the Falkland Islands

before you got into Pink Floyd. And even if you had, you probably didn't realize

that the dispute behind the war that erupted between the United Kingdom and

Argentina in 1982, and which inspired Pink Floyd's The Final Cut album,

had been brewing for hundreds of years.

If British prime minister Margaret Thatcher hadn't decided to bolster her political credentials by engaging Argentina in a 10-week war, Floydian history might have been very different. The band might have completed work on the Spare Bricks project, Roger Waters and David Gilmour might not have disagreed so famously and divisively about the direction the band was heading, and the string of hit records that started with 1973's The Dark Side of the Moon and ended with 1979's The Wall might have continued. Who knows--Waters might never have left the band at all!

• • •

Prior to 1982, it wouldn't surprise me if Roger Waters had never heard of the Falkland Islands. They were hardly an integral part of the British Empire. Slung about 400 miles off the eastern coast of Argentina, the island group known as the Falklands is made up of two large islands--creatively named East Falkland and West Falkland--and a few hundred smaller islands.

The western world discovered the Falklands in the 16th century, but the first recorded landing was not made until 1690, when the British claimed the islands and named them for Viscount Falkland, the Treasurer of the British navy.

The first permanent settlement was founded in 1764 by a French navigator, and eventually populated primarily by French settlers from St. Malo. Given their roots, they called the islands the Iles Malouines ( later corrupted to las Islas Malvinas by Spanish speakers, who still use this name).

The islands have been a source of international dispute for centuries. In the late 1760s the Spanish and English governments apparently spent a lot of time and money (though not necessarily lives) throwing one another off the islands and reclaiming them for strategic reasons. A 1771 agreement settled the dispute in favor of the British, but by 1774 the British military had formally evacuated the islands, leaving behind a plaque saying that the islands still belonged to the British Crown. And as revolution fever gripped the Americas in the half-century that followed, newly-independent Argentina claimed possession of the Falklands in 1820, and set up Argentine settlements there over the next decade.

The upstart United States played a small role in re-establishing British control over the Falklands. In 1831, Argentine forces arrested three US ships for hunting seals in the area. The US, always eager to protect its commercial interests with military firepower, retaliated by destroying the Argentine settlement and, strangely, declaring the islands free of all government.

Naturally, the British took offense to this and, fearing that the US was trying to muscle in on their Royal Majesty's turf, the British Navy swooped in and planted another plaque re-affirming that the Falkland Islands were a British possession in 1833. They eventually ran the Argentine presence off the island and set up their own colony of some 1,800 settlers.

Nonetheless, the Argentine government continued to assert that the Falklands rightfully belonged to Argentina, and over the years there was a significant rise in nationalist sentiments among the few Argentinians living in the Falklands. In 1964 the two nations took their cases to the UN committee on decolonization, and entered into protracted UN-mediated discussions on the situation that were still going on in 1982.

• • •

In 1982, the population of the Falklands was still only about 2,000 people (the current population is under 3,000), most of whom spoke English and preferred to remain under English rule. But the Argentine government was planning an invasion of the Islands, presumably to direct attention away from Argentina's miserable economy, which saw 600% inflation and serious declines in manufacturing output and wages.

|

Leopoldo Galtieri, left, with Jorge Rafael Videla, another high-ranking

junta official. |

Under the leadership of President Leopoldo Galtieri, a former commander in the military junta that had seized power in 1976, the Argentine government authorized an invasion of the Falklands. Code-named Operation Rosario, the invasion took place on April 2, 1982, when thousands of Argentine naval troops landed and forced the British to evacuate to nearby Uruguay.

The ploy worked--union demonstrations in Buenos Aires (the Argentine capital) gave way to spontaneous public displays of support for the government overnight. Within days, however, the UN had passed resolutions calling for the Argentinians to pull out, and US Secretary of State Alexander Haig met separately with British and Argentine officials to help speed negotiations.

By April 17, however, talks had broken down, and a week later the British government advises British nationals in Argentina to evacuate. On April 25 a British commando force re-took one of the islands, and the war was officially on.

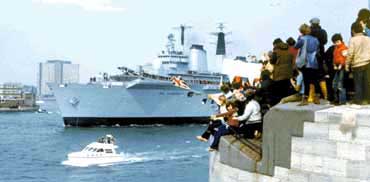

|

At Portsmouth, just miles from Southhampton, a crowd gathered to bid

farewell to the departing British task force. |

The fighting itself reads like most modern conflicts: planes are shot down, ships are bombed and sunk, amphibious invasions. Cease fire terms are discussed, and rejected. The US threw its moral support in with the British and handed down economic sanctions against Argentina, and the UN made peace proposal after peace proposal. After 72 days of extensive fighting, some 236 British and 655 Argentine casualties, and a cost of approximately $2 million, the British forced the Argentine forces to surrender (the only condition of surrender being the removal of the word 'unconditional' from the surrender terms).

|

The HMS Coventry was sunk by Argentine forces in just 15 minutes. |

Argentine president Galtieri resigned in shame shortly thereafter, but British prime minister Margaret Thatcher swept in an era of jingoistic British nationalism and won herself an election (and a lot of public support). Sure, the bad guys lost; the oppressive South American military junta was humiliated and crushed. But the 'good guys' came off like the usual bunch of Western hemisphere good-old-boy bullies throwing their weight around and having their way with the world.

Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges compared the Falklands conflict to "two bald men fighting over a comb", in that neither nation had much need for the islands, but neither was willing to back down.

|

| Margaret Thatcher |

Throughout The Final Cut Waters sprinkled direct attacks on Thatcher, Galtieri, US president Ronald Reagan, and Haig (as well as many more overbearing political leaders of the 20th century), whom he called "overgrown children". He railed against the mindless nationalism that blue-collar Britain embraced after demonstrating such authoritative military dominance over a third-rate despot. And he grieved the fact that 40 years after his own father's death young men were still being sent off to fight and die in order to settle disputes between egomaniacal world leaders.

Mike McInnis is a Spare Bricks staff member.