They Were All Left Behind: The Royal Fusiliers Company Z

A closer examination of the place where the tigers broke free

by Edward D. Paule

|

The Royal Badge of the Fusiliers -- The Tudor rose surmounted

by the crown. |

Prologue

You are about to begin a journey -- a journey through the past. It is with great pleasure and humble respect that I bring you the story of the 8th Battalion Royal Fusiliers City of London Regiment. For it is with this unit, Company "Z" to be exact, that Eric Fletcher Waters fought the fight against fascism.

This article has been compiled from numerous references. Unfortunately, one key reference was unobtainable. The British Army will only give out the service records of its soldiers to those that can prove kinship. As such, I cannot tell you the exact time at which Eric Waters joined the ranks of the Fusiliers.

Therefore, I will concentrate on the actions in Italy. For which his participation is well known.

An Ancient Regiment

The history of the Royal Fusiliers goes back to the 17th century. After the English Civil War, Charles II combined the Stuart and Cromwellian forces to create the modern British Army (1660). The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) was formed in 1685 as the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers.

But what the heck is a Fusilier? To answer that question we need a little perspective. Imagine that time long ago, that time of pikes and swords and cannons. Visualize that time when guns were very crude. In the 17th century, the most common type of gun in use by the army was the matchlock.

The matchlock used a slow burning wire to fire the gun when triggered. Like a fuse, the men carried around guns with an open flame. As such, the guys with guns were not allowed to go near the positions of the cannons. Open barrels of gunpowder and lighted matches were a deadly accident best avoided. But avoiding the cannons meant leaving them undefended against a close attack. This was a problem in search of a solution.

Then came the invention of the fusil (pronounced fusee, originally a French word). The fusil was an early flintlock weapon, which used a piece of flint to create a spark to fire the gun. As is typical with new weapons, they were initially quite expensive to make. So only small companies were formed equipped with the matchless gun. The basic function of the Fusiliers was to provide the artillery with much needed protection. But this specialty of protecting artillery didn't last long; by 1700, flintlock weapons (muskets) were available for everyone; and henceforward, the Fusiliers were no different from other infantry.

Throughout it's long history, the regiment has earned honor after honor in battle, including the War of the League of Augsburg (1689-97), the French Revolutionary Wars (1793-1802), the Crimean War (1854-5), World War I (1914-1918), World War II (1939-1945), and the Korean War (1950-3) to name but a few.

1939 - 1941 The Home Front

The Nazis had invaded Poland. A state of war now existed between Britain and Germany. The small peacetime army needed to be enlarged. And so, in September 1939, the 8th Battalion of Royal Fusiliers was raised from volunteers.

The first order of business was training. Then onto Kent, where the battalion spent all of 1940 defending the beaches from an invasion that never came.

All of 1941 was also spent at home in England. But in 1942, with the Americans joining the fray, it was time for Britain to go on the offensive. The 8th Battalion would now go overseas.

|

Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East |

1942 The Middle East

They boarded the transport Almanzora at Gourcock on the Clyde1. Along with rest of the 56th Division embarked in various transports and a navy escort, the convoy set sail. South, south, and south they steamed to the Cape of Good Hope. After rounding the southernmost tip of Africa, they continued northeast and in October reached Bombay, India.

|

British 56th Infantry Division • Organization Chart |

| 167th

Brigade 8th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers 9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers 7th Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry |

| 168th

Brigade 10th Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment 1st Battalion, London Scottish 1St Battalion, London Irish Rifles |

| 169th

Brigade 2nd/5th Battalion, Queen's Royal Regiment 2nd/6th Battalion, Queen's Royal Regiment 2nd/7th Battalion, Queen's Royal Regiment |

| Note: A typical battalion consisted of around 35 officers and 800 other ranks (enlisted men) or about 7500 men for the full division. |

After a quick switch to smaller ships, the division was on its way to Basra, Iraq on the Shat-Al-Arab, where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers flow into the Persian Gulf. Then by rail they traveled through Baghdad north to Kirkuk and camp was made amongst the oil fields.

The 8th Battalion of Royal Fusiliers had been sent to northern Iraq to build the next line of defense against the Germans. German successes in North Africa and South Russia had made this a possibility. But with defeats at El Alamein and Stalingrad along with an Allied landing in Morocco, by the time the 8th Battalion arrived in Kirkuk, the Nazi threat had evaporated.

North Africa

Five months of training in Kirkuk ended with orders to move up to the front. After three and a half years, the Fusiliers would finally get their turn at bat. On 28 March 1943, the 56th Division began its three thousand mile trek to Tunisia.

If their long watery trip from Britain to Iraq had left them praying for dry land, then they got it. Sand, sand, and more sand, traveling by road, they crossed Transjordan and Palestine and onto Cairo. Along the coast road, they passed by the wreckage of many earlier battles: Mersa Matruh, Tobruk, Benghazi, Tripoli. Arriving in Enfidaville on April 24, the 56th Division joined the British 8th Army to deliver the final crushing blows to Field Marshall Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps.

On 9 May 1943 came the orders to attack. Casualties taken this day (41 killed, 101 wounded) were but the first. Over the coming year, many more men of the 8th Battalion would fall at the hands of the enemy. They had shown courage under fire. They had now earned a measure of respect from their peers, continuing the legacy of the proud Fusilier legacy.

On 13 May, the war in Africa was over. The remaining Germans surrendered after the latest Allied assault left them in a hopeless position. The 8th Battalion was then moved to Tripoli to train for the invasion of Europe's "soft underbelly"2.

On 10 July, Operation Husky (the invasion of Sicily) began. This was the first step to knocking Italy out of the war. Doing so, would force Germany to take up their positions or surrender southeastern Europe by default.

Italian support for the war effort eroded quickly. On 25 July, their dictator, Benito Mussolini, was sacked. Shortly after the Allies completed their conquest of Sicily, the new Italian government surrendered. A fact that was kept secret for five days until publicized on 8 September.

Back in Africa, the first batch of replacements for the 8th Battalion had arrived. This brings the first opportunity for 2nd Lieutenant Eric Fletcher Waters to have joined the 8th Battalion in the field. Mr. Waters had not made the long trip to the Middle East. Eric was a schoolteacher when the war started. As a devout Christian and pacifist he did his part for the war effort by driving an ambulance. Only after he and his wife Mary joined the communist party did Eric feel it was right to fight. 3

While the 8th Battalion spent the winter of 1942/1943 in Kirkuk, Iraq, Eric Waters was safe home in his bed. At this time, a child was conceived; George Roger Waters would be born on 6 September 1943.

Salerno

'Operation Avalanche' was next: the invasion of the Italian mainland near Salerno. The Allies needed to take advantage of the success in Sicily, and to do so quickly.

|

| Royal Fusiliers boarding transports at Tripoli -- 5 September 1943 |

The convoy sailed from Tripoli on 8 September. The announcement of Italy's surrender at this time was a psychological blunder. Troops began to think that the invasion would be an uncontested cakewalk. But in reality, Germans had replaced Italians in the defenses; thereby making the assault more difficult, not less.

The Northern Attack Force (British X Corps - 46th and 56th Infantry Divisions) landed just south of Salerno on beaches codenamed Uncle, Sugar, and Roger. The Southern Attack Force (American VI Corps - 36th and 45th Infantry Divisions) landed further south at Paestum on beaches Red, Green, Yellow and Blue.

On D-Day, the day of the landings (9 September), the Allies engaged the Germans (16th Panzer Division) in an extremely fierce contest for the beaches. The Germans held the high ground and the exits from the beaches. The eight miles separating the American and British forces prevented them from providing mutual support. Demoralized, thoughts of a cakewalk fell from their minds.

After landing, the 46th Division turned left to occupy Salerno. The 56th Division headed inland. The four companies of the 8th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, had fifteen miles paved in blood to reach their objective, the high ground northeast of Eboli. Starting at the beach, Company "Z" dispatched a German battery by means of a successful bayonet charge. On a lateral road, a half mile inland, "W" and "X" Companies ran into five German tanks of the flamethrower variety. Lacking tanks of their own, the Fusiliers suffered heavy and horrible casualties to these mechanized dragons. "Y" and "Z" Companies moved up to help, but it wasn't until a squadron of friendly tanks arrived, that the over-aggressive German tanks were knocked out.

On 10 September, the 8th Battalion moved up to St. Lucia. There, they defended against a German counterattack on the 11th. The 29th Panzer Grenadiers Division, after successfully evacuating from Sicily, had arrived in Salerno battlefield that day. The Hermann Goering Panzer Division had come down from Naples, too. Other Divisions would be arriving soon.

On 12 September, German counterattacks pushed the British out of Battipaglia, a town that was being held by the 9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers. Even stronger German counterattacks occurred the following day.

After four days of continuous fighting, the 8th Battalion was in need of relief, but the beachhead was still too small for the reserves to land. So on 14 September, the 8th Battalion was relocated to a "quiet" sector on the hills north of Salerno, a sector that had belonged to the 46th Division. It ceased to be quiet the day the Fusiliers arrived, as a German counterattack in this sector had just begun. The 8th Battalion held their positions around the village of Piegollellel.

With the crisis averted and the continued build-up from reinforcements, the Allies were ready to break out from the beachhead.

On 16 September, Field Marshall Albert Kesselring, commander of all German forces in southern Italy, gave up on his hopes of annihilating the beachhead. He would fight delaying actions at natural defensive positions, of which there were many.

|

| The 8th Battalion moves forward -- 16 October 1943 |

With the Apennines Mountains in the center, and many rivers flowing to the sea, moving up the Italian peninsula was nothing but one obstacle after another. The cold and mud of the coming winter would make advancement that much more difficult. This would give Kesselring the time to build and strengthen a line that would hold off all attacks, the Gustav Line.

On 20 September, the 8th Battalion received some reinforcements. Here was the next opportunity for Eric Fletcher Waters to join up with the Fusiliers in the field. Counting men lost from an ambushed patrol on the 22nd, the 8th Battalion had lost 206 men during Avalanche. 4

The German withdrawal did bring some gifts. With the 8th Battalion in the van, the 56th Division marched past Pompeii and Mt. Vesuvius and entered Naples on 1 October. The entire populace turned out clapping and cheering; and bestowing flowers, fruit, and wine upon their liberators.

The Gustav Line

|

| The 8th Battalion on Monte Camino -- 7 December, 1943 |

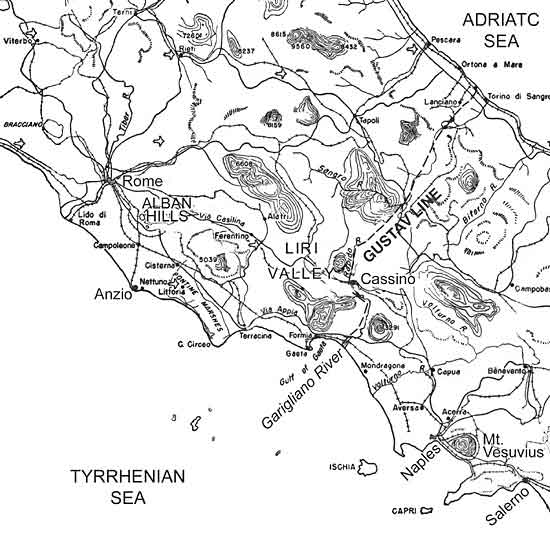

After battling the Germans to cross the Volturno River, the 8th Battalion worked to clear the area approaching the Garigliano River, including Monte Camino, a 3000-foot peak, taken after heavy fighting. This opened the way to crossing the Garigliano and Rapido Rivers, the gateway to the Liri Valley, the next stop on the drive north. But the gates to the Liri Valley were closed.

From the Gulf of Gaeta, on the Tyrrhenian side, to Ortona on the Adriatic coast; along the Garigliano and Rapido rivers; dug in on mountain slopes--this was the Gustav Line. This was Kesselring's fortified position designed to halt, not just delay, the advancing Allies.

It took three months to move from Naples up to the Garigliano. On 21 December, the 8th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, took their place on the banks of that river, starring at the Germans on the other side.

It was stalemate at the Gustav Line. The rugged terrain, the narrow isthmus, the winter weather, the diversion of reinforcements to England for the upcoming main event (the invasion of Normandy), the tenacious defense of a dug-in foe; all worked together to halt General Sir Bernard Montgomery's Eighth Army on the right and General Mark Clark's Fifth Army on the left.

A flanking maneuver was needed to dislodge the enemy. With British Prime Minister Winston Churchill playing general, the high command chose to land troops by amphibious assault at Anzio. It was hoped that the appearance of Allied troops behind the enemy's right combined with a new offensive toward the Liri Valley would compel the Germans to retreat. Even if the outflanking proved unsuccessful, at a minimum it would force the Nazi's to weaken the Gustav Line by diverting units from there to Anzio.

The plan was for the British 46th and 56th Divisions to assault across the Garigliano and establish a bridgehead on the left-hand side of the Liri Valley entrance. This was to be a diversion, to get the Germans to commit their reserves to this sector. Then, the American II Corps would provide the main thrust by assaulting across the Rapido River and establish an exploiting bridgehead at Cassino on the right-hand side of the Liri Valley entrance.

And so it came to be for the 8th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, crossed the Garigliano on the night of 17 January, 1944. After crossing the water and then a minefield, they began to attack their objective, a hill known as Monte Damiano. "X" and "Y" Companies took the lead, with "Z" Company exploiting through them. The 8th Battalion took many casualties in clearing the enemy from that hillside.

They patrolled and expanded their bridgehead on the 18th and 19th. The British success across the Garigliano had achieved its goal. Without hesitation Kesselring committed his reserves then and there. 5

The counterattack came on the 20 January. All day the 8th Battalion was pounded and were eventually relieved by the 1st Battalion, London Scottish of the 168th Brigade.

It was time again for the depleted battalion to head to another "quiet" sector. Unfortunately, the town of Lorenzo was still in German hands. The Fusiliers spent their quiet time fighting house-to-house and street-to-street to evict the Nazi tenants.

The plan called for the Garigliano bridgehead to be just a diversion. But, its success had left General Mark Clark wishing his plans were different. If only the II Corps was positioned to exploit the British advancement, instead of making its own futile assault on Cassino.

The 8th Battalion of Royal Fusiliers got a much-needed period of rest starting on the 23rd. A letter of congratulations came from the Corps Commander for their role in capturing and holding Monte Damiano against the 29th and 90th Panzer Grenadier Divisions and part of the Hermann Goering Division. 6 8th Battalion casualties amounted to 144 and another batch of replacements arrived on 26 January. For certain, Eric Fletcher Waters was now standing on Italian soil amongst his fellow Fusiliers.

Anzio (Operation Shingle)

|

| Anzio -- An army reconnaissance photograph taken just before the assault |

Anzio, 37 miles south of Rome, was a seaside resort for the ancient Roman Emperors. Now it would be the seen of the longest beachhead struggle of the war.

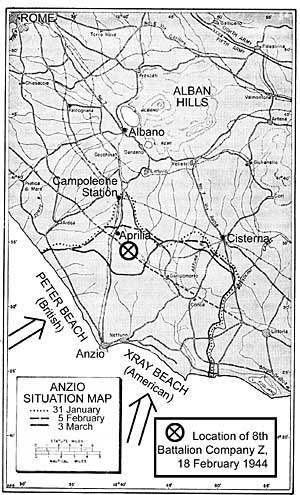

D-Day was 22 January, 1944. The Americans (3rd Infantry Division) landed south of Anzio on beach "X-ray". The British (1st Division) landed north of Anzio on beach "Peter". Twenty miles north of Anzio lay the Alban Hills. If the Allies could take control of these hills, they would dominate the landscape; severing Nazi communication between Rome and the Gustav Line. Rome itself would then be within easy reach. Such success would cause the Germans to abandon the Gustav Line or at a minimum weaken it enough for the main army (Clark's 5th and Montgomery's 8th) to break through. It was anticipated that the troops landed at Anzio would link up with the main army within 10 days. But this was not to be.

The landings were unopposed, save for a few land mines. By midnight of that first day, 36,000 men were ashore.

Troops began moving slowly to their predetermined initial objectives. The going was easy. A sense that their assault had surprised the Germans came over them. But they were mistaken; Field Marshall Kesselring had already made plans in anticipation of such a move. He only needed to give the code word "Richard" to have designated units move on Anzio. 7

|

| Anzio -- The Americans landing on beach X-ray |

Kesselring needed to move quickly. A rapid maneuver could seal the Allies within their beachhead without diverting any troops from the Tenth Army holding the Gustav Line. The Allies had mistakenly assumed a rapid deployment by the Germans was impossible. Allied Intelligence had reported that earlier Allied Air Force attacks on the roadways and railways around Anzio would prevent any rapid German response. This error would weigh heavily on the battle's outcome.

As each day passed, LSTs (Landing Ship Tanks) would bring more men and equipment up from Naples. Soon, VI Corps, as the combined American and British force was designated, held a beachhead about seven miles deep and fifteen long.

By the 28th, VI Corps had expanded beyond the range of naval gunfire support and into stiffening enemy resistance. It was on this day, that Hitler issued another of his propagandic orders, "The landing at [Anzio] is the beginning of the invasion of Europe planned for 1944. [All German forces] must be filled with the fanatical will to emerge from this fight victorious, and not rest until the last enemy has been destroyed or thrown back into the sea. The battle must be waged with holy hatred towards a foe who is fighting a merciless war of extermination against the German people." 8 Kesselring would come close to carrying out the Fuehrer's wishes.

After a week of unloading, General John Lucas, commanding the VI Corps, had 69,000 men, 500 artillery pieces, and over 200 tanks. VI Corps was now prepared to attack. The objectives were the towns of Cisterna and Campoleone Station. A two pronged attack on the vital Rome-Naples railroad and of the highways leading directly to the Alban Hills.

But a week had given the rapidly redeploying Germans sufficient time to build Cisterna into a stronghold. If attacked a day or two before, Cisterna would have been an easy victory. Why had the Allies waited so long? It seems Clark had given Lucas a case of Salerno-itis, "Don't stick you neck out Johnny. I did at Salerno and got in trouble" 9 General Lucas had no real intention of dashing over to the hills. Assuming he was successful in doing so, he felt that he could not hold the hills and a long supply line to the coast from a counterattack with what few forces he had. At the last moment, his orders were changed from "take" the Alban Hills to "advance" towards the Alban Hills.

Both the American attack on Cisterna and the British attack on Campoleone Station were failures. Lucas expected to encounter weak enemy defenses designed to slow him down. But on the night of 29 January when attack began, the German 16th Panzer Division had moved into place. The Allies struggled for two days against the mud and dug in defenders. Loses were high, 1500 killed, missing, or captured. General Lucas determined that continuing the attacks would mean useless sacrifice.10

Generals Clark and Alexander (Clark's boss) paid General Lucas a visit. They were not pleased with his performance. General Lucas wrote in his diary, "[It] is certainly bad for me. [General Clark] thinks I should have been more aggressive on D-Day... My head will probably fall in the basket, but I have done my best."

All fronts in Italy were now at standstill. Had it been logistically feasible, the bulk of the army could have been shifted to Anzio. Anzio could have then be the main thrust instead of just a diversion. But there were insufficient ships to carry out such a plan. So, on 3 February, General Clark gave General Lucas the order to sit tight and dig in, "Your beachhead should now be consolidated and dispositions should be made suitable for meeting an attack. ... Previous orders to take Cisterna and Campoleone Station are cancelled."11

On the other side of the line, Kesselring now had the equivalent of 5 divisions in and around the Alban Hills. The thought of rubbing out the Anzio beachhead must have elated him. He definitely had the forces to do so, and Hitler had ordered him to do just that.

On 5 February the 14th Army, as the hodge-podge group of German units from numerous divisions was now called, began its first counterattack. German artillery pounded the Allies, and the Luftwaffe (the German air force) bombed away with deadly accuracy. The Allies had yet to obtain air supremacy.

Day after day, the battle raged. The British 1st Division, especially the 24th Guards Brigade and the 168th Brigade, took on the brunt of the attack. The latter had just been brought up from the 56th Division to reinforce the 1st. In less than 3 weeks, the 1st Division had lost half its strength--heavy casualties indeed!

Combat came to a halt momentarily on 12 February. Their first counterattack having only partial success, The Germans needed to regroup before launching a second. General Lucas took the opportunity to relieve the battered 1st Division. The remaining two brigades (the 167th and the 169th) of General Gerald Templer's British 56th Division were brought up from Naples. They quickly dug in preparation for the next counterattack. The 8th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers took their position southeast of Aprilia. Eric Fletcher Waters was now on the front line.

The Allies now had 5 divisions on the ground in Anzio (two British, three American). Facing them was a bloating German force of 135,000 men (the equivalent of ten divisions). Certainly, the Allies were now on the defensive. There were non-passing thoughts of another Dunkirk.

On 16 February, the German assault on the beachhead renewed. The main attack came down the Albano-Aprilia-Anzio highway. Spearheading the first wave were the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division and the 715th Infantry Division. Exploiting behind them were the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division and 26th Panzer Division. This massed armor would take advantage of any breach in the Allied lines and advance on the city of Anzio itself.

The line at Aprilia, were so many of the British 1st Division had fought and died was now being defended by the American 45th Division on the left and the British 56th Division on the right. The fighting was extremely heavy, the heaviest combat of the campaign to date.

Company "X" of the 8th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, was overpowered. When the order came to withdraw that night, only one officer and twenty men did so. Company "Y" had it worse, with only one officer and ten men surviving. The Allies had held that day, Company "Z" was still in position, but another onslaught would come that night.

Using infiltration tactics, the Germans managed to create a small gap in the American side of the line. In the early morning of 17 February, they pressed home their advantage. Six battalions of German infantry and about 60 Tiger tanks hit the gap with Luftwaffe fighter-bomber support. Soon the Tiger's had broke free and drove a wedge two and a half miles deep into the center of VI Corps. The Germans had hoped to do better, but with the help of artillery and nightfall, the new Allied lines held.

|

| A German Tiger tank |

This was the most important day in the struggle for control of the Anzio beachhead. This was the day of Kesselring's all-or-nothing attempt to break the final Allied line of defense. This was the day that Eric Fletcher Waters would die. 12

After first beating off the German attack, 8th Battalion Company "Z" became hard pressed. In heavy fighting, the company had become surrounded. With no means of sending assistance, the Battalion Commanding Officer could do nothing as Captain Harry Witheridge and the remaining men of Company "Z" were taken prisoner. 13

At this key point, German supplies of artillery ammunition had become dangerously low. But the Allies' big guns had plenty of ammo and the German attackers were blown to bits. Their maximum point of advance did not reach closer than 7 miles from the beach.

On 19 February, the Allies counterattacked causing the Germans to fall back. General Lucas' premonition of his own demise came true on 22 February, as he was relieved of his command.

The Germans made a final assault on 29 February, this time against the American sector south of Cisterna. With this last ditch effort thwarted, Kesselring gave the order to cease attacks and dig in. And so began a period of stagnation, with neither side capable of launching an attack.

On 3 March, Churchill wrote, "There could be no hope now of a break-out from the Anzio beachhead, and no prospect of an early link-up between our two separated forces until the Cassino front is broken." 14

On 9 March, the 8th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, sailed back to Naples. After eighteen days in Anzio, they had incurred a massive 443 casualties. A few hundred ordinary lives that helped to prevent the collapse of the Anzio beachhead (or bridgehead as was used interchangeably by the British).

16 May brought the start of a new, and finally successful, attempt to break the Gustav Line. Finally, on 25 May the Anzio beachhead was linked up with the main line, and on 31 May, the high ground of the Alban Hills was seized. Then on 4 June, Rome was liberated--a glorious feat that was overshadowed two days later.

|

| A disabled Tiger tank lies in an Italian ditch |

The Allied success at Normandy was insured by Anzio. For it was Anzio that forced Kesselring to commit all of his reserves. It was Anzio that convinced Hitler that the Italian campaign was a major Allied effort. It was Anzio that forced Hitler to send eight additional divisions to reinforce Kesselring's position. In so doing, the Allies stamped the word "success" on Anzio and the entire Italian campaign, for this was the goal: tie up as many divisions as possible in Italy. Eight more divisions in Italy meant eight less divisions in northern France.

Epilogue

I hope you found this article educational. I know I learned a lot in writing it. Hopefully, I'll be able to find out when Eric Fletcher Waters joined with the other ranks in the field. Then, I can do a rewrite, and answer that burning question, "Was Eric F. Waters an experienced veteran or as green as green can be on that fateful day in black '44?"

A new Royal Regiment of Fusiliers was formed in 1968 by the amalgamation of the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers, the Royal Warwickshire Fusiliers, the Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment), and the Lancashire Fusiliers. This new regiment consists of three regular and two volunteer battalions.

Today, a museum dedicated to the Regiment is located in Her Majesty's Tower of London. And rightfully so, for it was within the Tower that the royal cannon were kept and where the original Fusiliers were garrisoned in the 17th century.

Ed Paule is a guest contributor to Spare Bricks.

Notes

1 C. Northcote Parkinson, Always a Fusilier

(London, 1949) p. 102

2 "The soft underbelly" is a term first used by Winston

Churchill to describe Italy as being Germany's weak spot.

3 Vernon Fitch, Pink Floyd The Press Reports (Burlington,

2001) p. 279

4 Always a Fusilier p. 140

5 Carlos D'Este, Fatal Decision - Anzio and the Battle

for Rome (New York, 1991) p. 82

6 Always a Fusilier p. 153

7 Samuel Eliot Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio - History

of the United States Naval Operations in World War II (Boston, 1975) Volume

IX, p. 343

8 Fuehrer Directives 1942-45 pp. 121-22

9 Fatal Decision p. 133

10 Sicily-Salerno-Anzio p.358

11 Lucas Diary; Calculated Risk p. 298

12 Vernon Fitch, The Pink Floyd Encyclopedia (Burlington,

1999) p. 326

13 Always a Fusilier p. 159

14 Closing the Ring pp. 487-8

All photographs are used without permission. Sorry.

Other Reference Books:

Eyes of the War - A Photographic Report of World War

II (New York, 1945)

George Cameron Stone, A Glossary of the Construction,

Decoration and Use of Arms and Armor in All Countries and in All Times (New

York, 1934)

Internet References:

United Kingdom (British Empire & Commonwealth Land Forces)

http://regiments.org/milhist/uk/uk.htm

The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers http://www.british-forces.com/fkac/history/regiments-coprs/royalregtfusiliers.html#pred