Features

This one's Pink

Unraveling the mysteries behind the Pink Floyd name

Ask the average music fan where the name 'Pink Floyd' came from, and you'll get a blank stare at best. And while most serious Floyd fans can correctly give the surnames of Misters Anderson and Council, most are not even remotely knowledgeable about their music. This only makes sense: Pink Anderson made very few recordings at all (and it seems unlikely that Syd Barrett ever heard any of them), and Floyd Council made even fewer--so few that even after 40 years of searching, Pink Floyd fans cannot seem to find them.

The result is that both Anderson and Council are basically remembered only as minor footnotes to rock and roll history, and that seemingly more by circumstance than by any major musical influence on the band that bore their names. In fact, those footnotes are frequently inaccurate and confusing. (For example, they are sometimes called "Georgia bluesmen" despite the fact that they hailed from the Carolinas.)

Even the details of how Barrett became acquainted with their names have become muddled over the years. As the story goes, Barrett took the names from his record collection. Some take this to mean that Barrett owned a record by Pink Anderson and another by Floyd Council, and perhaps he saw the sleeves side-by-side and had a flash of inspiration. Others suppose that both Anderson and Council appeared on a blues compilation album in Barrett's collection. A few even wishfully believe that Anderson and Council made a recording together.

Fact: There is no known recording of Floyd Council and Pink Anderson together. Fact: There is no solid evidence that the two ever played together, or even met. Fact: There is no known blues compilation album that features both of them. Fact: There are no known released recordings (let alone an entire album) under Floyd Council's name (though a few 1937 solo recordings were apparently issued under the name "Blind Boy Fuller's buddy").

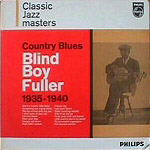

This Blind Boy Fuller compilation was likely Syd Barrett's source for the names 'Pink' and 'Floyd'.

|

These facts alone are enough to poke holes in most theories of how Syd came to know these obscure names. But allow me to pose another theory, one with at least a shred of evidence to support it. In 1962, the Philips label released a Blind Boy Fuller compilation called Country Blues 1935-1940 (BBL-7512). On the sleeve notes, blues historian Paul Oliver wrote "Curley Weaver and Fred McMullen, (...) Pink Anderson or Floyd Council--these were a few amongst the many blues singers that were to be heard in the rolling hills of the Piedmont, or meandering with the streams through the wooded valleys."

Finally! The names are side-by-side in print, years before Syd Barrett made them famous in very different circles. Is this the record that was part of Barrett's collection? Was it Paul Oliver who first put the name of Pink Anderson and Floyd Council together? Is it pure luck that Barrett didn't decide to name his band "Weaver McMullen", or "The Curley Fred Sound"? I believe that it was. And perhaps more importantly, I suspect that Barrett may have never heard the music of Pink Anderson or Floyd Council (unless one of Council's seven recordings with Fuller was included on that compilation). It may well have been the music of Blind Boy Fuller that Barrett found so inspiring.

Nonetheless, we are not fans of a band called "Blind Boy Weaver". Whatever the reason, Pink and Floyd are the names Barrett borrowed, and as such Anderson and Council are the men he immortalized. Without Barrett's influence, I'm sure both would be long forgotten to all but the most dedicated blues enthusiasts.

Floyd Council

Floyd Council (photo by Kip Lornell, from Living Blues magazine)

|

Floyd Council was born September 2, 1911 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. By the 1920s he was a street musician under the tutelage of Leo and Thomas Stroud, and in the 1930s he worked on occasion with the blind singer/guitarist Blind Boy Fuller. Fuller is remembered mainly as a blues musician, but he also played the country ragtime and folk music of the region, and was a popular pre-war recording artist. He had been recorded in New York in the mid-'30s by ARC Records scout John Baxter Long, who is credited (perhaps erroneously) with composing some of Fuller's material.

Long reportedly heard Council playing on the streets of Chapel Hill in January 1937, and invited him to join Fuller and Long on a trip to New York the following week for a recording session. This was Fuller's third trip to New York, and Council's role was clearly that of a backing musician. Council made a second trip to record with Fuller in December, in sessions that also included Sonny Terry (who would later be cited by David Gilmour as an influence) on harmonica. During one these two trips recordings were made of at least six tunes featuring Council as a solo artist, released only under the name "Blind Boy Fuller's buddy". (Fuller's reputation was strong enough that other artists took names such as "Little Boy Fuller" or "Blind Boy Fuller No. 2"--or were given such names by record executives).

Council played in the Chapel Hill area in the 1940s, '50s, and '60s, and performed live on local radio stations from time to time, both as a singer and a guitarist. He was promoted as "Dipper Boy" Council and "The Devil's Daddy-in-Law", though it has been surmised that these nicknames were dreamed up by promoters. He gradually gave up on playing due illness, and in the late '60s he suffered a debilitating stroke, though he remained mentally sharp. In 1969, he told an interviewer that he had recorded a total of 27 tracks, mainly during those 1937 sessions in New York. At least 3 songs were recorded in 1970, following his stroke, but were never released. Council died in Chapel Hill on May 9, 1976 (according to his death certificate--a copy of which can be found here, for those so inclined--though other sources say he died in June 1976 in Sanford, NC).

Pink Anderson

Substantially more is known about Pink Anderson, and while his name is still fairly obscure, his recordings are more widely available. The irony is that Syd Barrett may have never heard the music of the man whose name he immortalized.

Pink Anderson (photo by Kip Lornell, from Living Blues magazine, early 1960s)

|

Pinkney "Pink" Anderson was born in Laurens, South Carolina on February 12, 1900. He was raised in nearby Greenville and then moved to Spartanburg, where as a child he would sing and dance in the streets for tips. At age ten, he began learning open-tuning guitar from a local musician named Joe Wicks. In 1916 Anderson met a blind singer named Simeon "Simmie" Dooley, who became young Pink's mentor, broadening his range and repertoire. Anderson recalled practicing in the woods with Dooley, who sang the songs again and again until Anderson learned the chords. Dooley would cut a switch and use it to hit Anderson's hands if he made a mistake. On one occasion he recalled having to perform at a country club party after an extended rehearsal, with hands so swollen from Dooley's switch that he could hardly play.

An example of the kind of remedies sold at medicine shows. This one was by the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company, a competitor of the Indian Remedy Company for which Anderson worked.

|

It was as a teenager--some sources say 1914, and others say 1917--that Anderson first went on the road as a traveling musician with the Indian Remedy Company. Such 'medicine shows' were still common at the time, especially in the rural south, with the proprietors hawking a variety of 'miracle cures', elixirs, and patent medicines--concoctions of herbs, spices, and often alcohol or opium. One of the largest and best-known of these companies was the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company, and the Indian Remedy Company probably took a similar name in order to trade on the Kickapoo company's reputation.

The medicine shows often included singers and entertainers whose performances would gather a crowd for the sales pitch. Anderson's employer was a fellow calling himself "Doctor" W. R. Kerr, though few medicine show salesmen had any sort of medical background. At first, Anderson mainly danced and told jokes, and sang a few traditional folk songs. As his guitar abilities improved, he added more of this to his medicine show performances. Simmie Dooley also worked for the medicine show on occasion, but Anderson claimed that the shows didn't like to hire blind performers because of the extra attention they required.

The medicine show business was not a full-time occupation, to say the least, and Anderson and Dooley performed at parties in the Spartanburg area on and off through the years. On April 14, 1928, the pair recorded four songs at a mobile recording unit that was set up in Atlanta, Georgia. Columbia Records issued two of the cuts ("Papa's About to Get Mad" and "Gonna Tip Out Tonight") on a 78-rpm disc under the name "Pink Anderson and Simmie Dooley" in 1928. The other two songs ("Every Day in the Week Blues" and "C.C. and O. Blues") were released later that same year. The first record sold well enough to warrant a second pressing, and Columbia offered to record Anderson again, this time without Dooley. Out of loyalty to his mentor, Anderson declined.

American Street Songs (1961), featuring the "Carolina Street Ballads" of Pink Anderson and the "Harlem Street Spirituals" of Rev. Gary Davis

|

Anderson traveled with the Indian Remedy Company until Dr. Kerr's retirement in 1945, and then worked for Big Chief Thundercloud's medicine show. On May 29, 1950, Paul Clayton recorded Anderson playing some of his medicine show material at the Virginia State Fair in Charlottesville. (Some sources suggest Anderson didn't find out that his performance was recorded until after the fact.) Seven of these songs saw release on a 1961 Riverside LP entitled American Street Songs (re-issued in 1987 as Gospel, Blues and Street Blues: Rev. Gary Davis and Pink Anderson, and eventually re-released on CD). Anderson's songs demonstrate his broad repertoire, born of necessity on the medicine show circuit, where you had to be able to draw a crowd in any location. The tracks range from minstrel show and vaudeville songs ("Greasy Greens", "I've Got Mine") and ballads ("John Henry", "The Ship Titanic", "Wreck of the Old 97") to traditional blues ("Every Day in the Week") and even country ("He's in the Jailhouse Now", by Jimmie Rodgers), for a total of nearly 26 minutes. The album's flip side contains music by Reverend Gary Davis, a guitarist/singer of both blues and traditional gospel who also hailed from Laurens County, South Carolina.

Though none of the material is original, Anderson's own touches are heard throughout, with new verses added and borrowed from other sources. In the 1987 release's liner notes, Daniel G. Hoffman wrote this: "As a result of 40 years of street singing Pink Anderson's voice is strong and rasping, and anyone within several blocks would surely hear and be drawn to it. Once having gained attention, he would sing a varied program of old ballads, blues, and minstrel vaudeville and popular songs calculated to evoke memories, share experiences, and enable his listeners to laugh at themselves and the world. His is a folk voice, and his version of traditional material have all been tempered and changed by time and personal experience. He is also a highly sophisticated entertainer, for street crowds are in many ways the most critical of audiences, with no inhibitions about letting a performer know if they dislike or are indifferent to him."

In 1957, heart trouble forced Anderson to retire from the touring with the medicine shows entirely. He continued to play in the Spartanburg area with a trio composed of himself, Charley "Chilly Willy" Williams on washboard, and Keg Shorty Bell on harmonica. After Simmie Dooley's death in 1961, Anderson made a series of recordings in Spartanburg for blues historian Samuel Charters. These were released by the Prestige/Bluesville label in the early 1960s, and all three have been re-issued on CD.

Pink Anderson, Carolina Bluesman, Volume 1

|

The first of these was entitled Carolina Bluesman, Volume 1 (1961), and showcased Pink Anderson as a blues musician for the first time on record. Much of the material is immediately familiar. "Baby Please Don't Go", for example, was originally recorded in 1935 by Big Joe Williams, and was later covered in 1965 by Van Morrison and Them (and subsequently by ACDC, Aerosmith, and others). The differences between Anderson's approach to the blues and the more widely popular Mississippi Delta blues are clear when you compare Muddy Waters' version of the same song, recorded just a year earlier. Anderson's version is stripped down to the barest essentials--melodic guitar lines, sparse rhythm strumming in the background, and a gently plaintive vocal delivery. As the liner notes put it, "A singer from the flat glare of the sun on the Mississippi Delta seems to shout his anger and his pain, while a singer from the Carolinas seems to sing with a melancholy shrug...".

But Anderson was apparently familiar with the Delta blues style as well. "Baby I'm Going Away", for example, borrows an often-recycled blues melody, and takes a verse from Muddy Waters' "Rolling Stone" (1950). "Mama Where Did You Stay Last Night" and "Thousand Woman Blues" both use another popular blues melody, variously recorded as "Key to the Highway" and "Crow Jane".

Much of Anderson's blues material focuses on the tried-and-true blues themes of sexual conquest, infidelity, and lost love ("My Baby Left Me This Morning", "Thousand Woman Blues", "Every Day in the Week"). "Try Some of That" is purportedly about a woman who sells cookies (mentioned briefly at the beginning and end), but the lyric is really just an extended double entendre. One can't help but think that this track included on this 'blues' album by mistake, because while their are a few blues touches in the guitar work, the basic song structure is more akin to minstrel music. In fact, you get the feeling that Anderson might well have used some of these lyrics in his medicine show performances, with verses like:

It's good for mis'ry in your back

Good for corns and bunions

You can even hear the chorus being used as a sales pitch for one of Dr. Kerr's patent medicines:

You ought to try some of that

Yes, you ought to try some of that

First thing in the morning

You ought to try some of that

Pink Anderson, Volume 2: Medicine Show Man

|

The second Prestige/Bluesville album, Volume 2: Medicine Show Man (1962), has Anderson performing traditional songs from his medicine show days. Several of these ("I Got Mine", "Greasy Greens", "In the Jailhouse Now") had been recorded 11 years earlier by Paul Clayton at the Virginia State Fair. These later versions are a little more polished, with some of the gravel and harshness gone from Anderson's voice, perhaps due to the more-relaxed studio setting. (Of note, the All Music Guide claims that this album was recorded in New York, though I didn't find any mention of this elsewhere.) Anderson's voice comes across as exquisitely expressive and warm, with a slightly nasal quality and slurred articulation not unlike that of Leon Redbone.

There are several songs about gambling and crime ("Travelin' Man", "In the Jailhouse Now", "Chicken"), and "South Forest Boogie" (a reference to the street Anderson lived on, also mentioned in "Ain't Nobody Home But Me") shows how the blues bled over into the non-blues numbers in Anderson's vast repertoire. Finally, "I Got a Woman 'Way Cross Town" is a very slow and loose version of the Ray Charles tune, and there are moments where Anderson seems to get a little lost, as though he's not entirely familiar with it. While the other songs give the distinct impression that Anderson has been playing this material for ages, and the inclusion of this slightly-disappointing cut makes me wonder if on some level Anderson (or perhaps Samuel Charters) was hoping to cash in on the popularity of Ray Charles' hit by including this cover.

The Blues of Pink Anderson: Ballad And Folksinger, Volume 3

|

The third album in the Prestige/Bluesville series was 1963's The Blues of Pink Anderson: Ballad And Folksinger, Volume 3. Several more songs originally recorded in 1950 were re-recorded here ("The Titanic", "John Henry", and "The Wreck of the Old 97"), while "The Kaiser" is another example of the historical folk ballad. "In the Evening" and "Betty and Dupree" would have fit equally well on the earlier compilation of blues material, and the instrumental opening of the latter suggests that Anderson was a formidable guitarist in his heyday. It is a shame that so much of his career went undocumented and unrecorded.

Songs such as "Boweevil", "Sugar Babe", and "I Will Fly Away" reveal a healthy cross-pollination between musical styles--folk, blues, and spirituals, respectively. Pink Anderson comes across as representative of American music as a whole, with a variety of disparate forms and influences coming together to create something completely unique.

Carolina Medicine Show Hokum & Blues

|

In 1962, another compilation of these same Samuel Charters recordings was released by Folkways Records, under the title Pink Anderson: Carolina Medicine Show Hokum & Blues. Ten of the tracks were recycled from the other releases, and the sleeve bears the statement "Recorded live by Samuel Charters in Spartanburg, 1961-62", calling into question the claim of a New York recording session. An eleventh track, "The Boys of Your Uncle Sam", does not appear elsewhere, and a twelfth track "See What You Done Done" is by Charles "Baby" Tate, a Spartanburg guitarist who played with Anderson from time to time in the 1950s and '60s.

Anderson also appeared in Samuel Charters' documentary film The Blues (referred to in some sources as The Bluesmen, and variously said to have been made in 1963, 1967, or 1973), and another recording from this film, "Old Cotton Fields of Home", was released on a soundtrack album on the Folkways label.

These early-'60s recordings led to some higher-profile shows, but a stroke in 1964 spelled the end of Pink Anderson's performing career. Musician Paul Geremia opened for Anderson at some of these later shows, and painted a very sad picture of Anderson's last years. "He was living in very poor conditions in a little house that cost him $50 a month." This amounted to more than half his retirement income, and Anderson resorted to rather desperate measures to make ends meet. "He was running card games at his house, and selling booze to people, moonshine, or whatever he could get. It's too bad. The guy was a real important person, culturally speaking, and he was virtually ignored. Even his neighbors had little inkling that he was a musician."

Pink Anderson's final resting place.

|

Anderson died on October 12, 1974, and was buried at Lincoln Memorial Gardens in Spartanburg. His son, Alvin "Little Pink" Anderson, had traveled the medicine show circuit with his father, and is now a blues musician himself, having learned guitar from both his father and Simmie Dooley. (As the story goes, Dooley tried to use a switch on Little Pink's hands the way he had on the elder Anderson, but Pink wouldn't stand for it.) Little Pink has spent years raising money to help preserve his father's heritage and save his house (250 South Forest St., Spartanburg, SC), and even performed at a tribute to Pink Anderson that was part of the 2000 Chicago Blues Festival.

Pink Anderson (left), with Alvin "Little Pink" Anderson.

|

In addition to the above releases, several of Pink Anderson's 1961 recordings have been re-issued over the years as parts of blues compilations, as have his 1929 recordings with Simmie Dooley. This discography lists most (though not quite all) of Anderson's recordings. The University of North Carolina also has a nice site on a variety of Piedmont blues musicians, including Pink Anderson, Floyd Council, Blind Boy Fuller, Baby Tate, and many more.

The Pros and Cons of Eric Clapton

How Roger Waters helped Slowhand rediscover his roots

"I've never come across music like that, or had to play that way before in my life. It really was off the beaten track for me. That gig was like playing John Cage or Stockhausen--wearing headphones with click tracks going on, being ready for cues, and things like that.

"I like to have the time where I can get away from being in the lead. It's like having a little holiday in a way. It gives you a sense of reality. If you lead your own band and you do a lot of promotion work and interviews yourself, you become wrapped up in yourself too much. And my ego tends to fly off the handle too easily. I get wrapped up in believing that what I do is faultless and I walk down the street and say, 'Hey, everyone feel all right? I'm feeling great'. So when you work with someone else you really have to learn how to slot in a band and make it sound good."

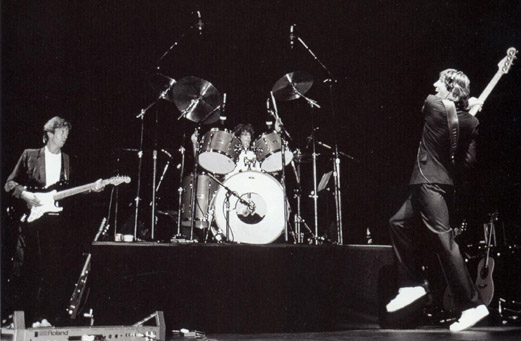

This is what Eric Clapton said about touring with Roger Waters soon after working together on The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hikingalbum and tour in 1983 and '84, in performances that provided what many of Eric's fans consider some of the most superb playing of his career.

Several forces have shaped Clapton's long, illustrious career. There is an ever-present desire to be faithful to (and respectful of) his traditional blues roots. At the same time, there is a certain restlessness that keeps him seeking for a new way to express himself. Finally, there is a certain tension between the 'guitar hero' status thrust upon him and his own desire to fade into the background as a member of a band, rather than stepping forward as the leader.

Clapton has always found his own stardom to be a source of great conflict, and it was not until the 1990s that Clapton would fully come to terms with his fame. To fully appreciate the role that Pros and Cons played in getting him to that point, we must examine his past.

The first choice in Clapton's musical path was his commitment to playing guitar, an instrument he noticed daily in a shop's window on his way to school. He taught himself to play, painstakingly reproducing the riffs he would hear on blues records. "I had to copy to learn," Clapton told biographer Ray Coleman, "and I'm still copying sometimes. I never had a teacher. I just heard a good song on the radio or on a record, and thought the chord changes sounded nice, so I picked up the guitar and copied them. So when I was learning, I had no technique whatsoever, and I never learned a thing properly. I made my business to copy, to mimic, as much as I could."

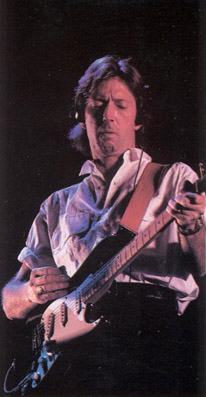

Eric Clapton on tour in 1984 with Roger Waters.

|

From then on, the foundation of Clapton's musical identity has been the blues, even as he has grown and developed in other directions. The blues have been a constant model both for the necessary emotion and structure of his guitar playing. The blues also provided a 'social' and moral model for Clapton--the model of a man standing alone with his music against life's adversities. Clapton has often used that image when describing himself in interviews, and recalls the image in his recent projects, such as his Me and Mr. Johnson and Sessions for Robert J, which detail his inspirational debt to the legacy of legendary bluesman Robert Johnson.

After cutting his teeth with a couple of London blues bands (first the Roosters, and later Casey Jones and the Engineers), Clapton joined the Yardbirds, a band that was to become a breeding ground for other giant figures in rock such as Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page. The Yardbirds gave Clapton his first taste of fame, but he eventually quit the group--whose main goal had been to have a hit record--because they had chosen a 'too commercial' pop song to release as a single.

John Mayall then asked him to join his Bluesbreakers, a band firmly committed to playing Chicago-style blues. The album Bluesbreakers helped put the electric guitar at the forefront of popular music. Eric took rock guitar from being merely an instrument of excitement and used it as a means of serious expression, and it was during his Bluesbreakers days that the 'Clapton is God' catchphrase first took off. Though Clapton's blues technique was exemplary, it was still fairly academic. He could faithfully reproduce the sounds of Otis Rush, Albert King, and the like, but he brought very little of his own identity to his playing. He was so concerned about authentically recreating the blues sound that there was very little room for his own interpretation.

At the same time, the restless Clapton longed to explore new territory, and quickly grew tired of Mayall's formulaic approach. "I wanted to go somewhere else, you know... put my kind of guitar playing in a new kind of pop music context." With Cream, he found a vehicle to do just this. As Coleman writes, "While the blues would always be the core of his playing, he could see himself planting that seed within a wider style. A new kind of rock 'n' roll, with a strong blues bias, its potential audience far wider than the club world, perhaps with a nod towards high fashion, and certainly with fresh lyricism, was needed to absorb Eric's energy."

Cream helped define an era of British blues-rock. The ten-minute solo, the drum solo, the bluesy vocals, everything that would be taken for granted in the next decade was here in its formative setting. Eric's improvisations "were lessons in inspirational creativity. He formulated a unique style, a feel for the blues in a modern-day framework," according to Coleman. "In a surprisingly short spurt of less than three years, Cream had given some of the most stunning performances, through the exceptional chemistry of three musicians who came together at the right time."

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ray Coleman, Survivor - The authorized biography of Eric Clapton, Futura Publications, 1986.

Mark Roberty, Eric Clapton - The New Visual Documentary, Omnibus Press, 1990.

Mark Roberty, Clapton - The Complete Chronicle, Pyramid Books, 1991.

Harry Shapiro, Eric Clapton - Lost In The Blues, Guinness Publishing, 1992.

Fred Weiler, Eric Clapton, Magna Books, 1992.

Mark Roberty, In his own words - Eric Clapton, Omnibus Press, 1993.

Mark Roberty, Slowhand - The Life and Music of Eric Clapton, Crown Trade Paperbacks, 1993.

Michael Schumacher, Crossroads - The life and music of Eric Clapton, Hyperion, 1995.

Mark Roberty, Eric Clapton - The New Visual Documentary, Omnibus Press, 1990.

Mark Roberty, Clapton - The Complete Chronicle, Pyramid Books, 1991.

Harry Shapiro, Eric Clapton - Lost In The Blues, Guinness Publishing, 1992.

Fred Weiler, Eric Clapton, Magna Books, 1992.

Mark Roberty, In his own words - Eric Clapton, Omnibus Press, 1993.

Mark Roberty, Slowhand - The Life and Music of Eric Clapton, Crown Trade Paperbacks, 1993.

Michael Schumacher, Crossroads - The life and music of Eric Clapton, Hyperion, 1995.

Blind Faith--Clapton's next group--failed to live up to its 'supergroup' expectations, but the group's tour of America was important to Clapton's musical development. During that tour "he met Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett. Delaney and Bonnie's brand of funky rhythm-and-blues was attractive to musicians because it was loose and enjoyable to play. There were fewer strictures than in the more conventional bands; the formula allowed players to stretch out without getting in each other's way. (...) When Blind Faith collapsed, he purposely ambled into a less organized lifestyle, he says. His direction through Delaney and Bonnie and Derek and the Dominos was not particularly fruitful for his career. But it was an essential diversion for his life. As a musician, he wanted to merge with others rather than command the limelight." This kind of thinking eventually helped set the stage for Clapton's playing backup to a dominating ego like Roger Waters'.

With Derek and the Dominos, Clapton returned to lengthy guitar solos that highlighted a fabulous collection of blues classics and original material. Nowhere was this more evident that on "Layla". Clapton poured an especially emotive quality into his lyrics and playing. "Almost overnight," says Coleman, "the power and delivery of the song transformed Eric Clapton from the guitar-hero syndrome into a singer-guitarist-songwriter of world stature."

The Seventies provided a turbulent but rich harvest for Clapton the musician. He recorded a number of classic songs, but by the end of the decade he had lost touch with his blues roots. His long experimentation with 'lighter' drugs--in what had been partly a bond to his artistry--had led to heroin addiction, causing him to spend three years in seclusion. He then shifted to alcohol as his drug of choice, which proved far more dangerous to him. He collapsed onstage near death while touring USA in 1981, seemed to lose his musical inspiration, and had difficulty leading a band.

But the hiring of a new band for his new album sessions--Money and Cigarettes was released in 1983--marked something of a fresh start for Clapton's solo work. In addition to other influences, the inspiration of the blues was more evident in his playing, and his songwriting skills shone through on a few tracks.

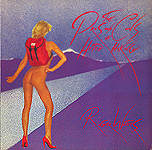

The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking

|

Eric Clapton had always been fascinated by Pink Floyd's music. In 1968, then with Cream, asked about his preferences on the groups performing on the British scene, he had immediately mentioned Pink Floyd. That band, he had said, was working differently from any group he had seen in America. This was actually a big compliment, in a moment in which Clapton was attracted by the psychedelic scene going on in the States, and his own band was among the most momentous in rock. So, in 1983, when Waters was planning his first solo album, The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking, Eric accepted his offer to play on it.

According to Clapton biographer Harry Shapiro, "Having worked so long with Dave Gilmour, Waters felt that much as he wanted to do everything himself, he still needed a strong guitarist. For his part, Eric was at a low ebb; he was not especially happy with Money And Cigarettes and generally felt he was losing direction. Despite the inspiration of Muddy Waters, rather than being lost in the blues, Eric felt he had lost touch with the blues."

Clapton's guitar and dobro sound gave a fine quality to Waters' epic, open-space music. "Roger was directing Eric back to what he did best," said composer Michael Kamen, who played keyboards on the album. "It was a horrible syrupy time for pop music at that point... And Eric, like most vital pop stars, was looking for this place in that market. What Roger succeeded in doing was getting Eric to refocus on the blues and on one particular track, 'Sexual Revolution', Eric played great blues. He was especially pleased with his playing on that track and actually said, 'You know, I think that's the best I've ever played on a record. If you take this on the road, I'll go with you'." (Of note, Clapton historians do not completely agree on whether or not he deliberately offered to join the tour rather than being asked to do it.)

The Pros and Cons sessions took place in August 1983, right after Eric's last American shows for his 'Money and Cigarettes' tour, while preparing for a couple of charity gigs, such as the Action Research into Multiple Sclerosis (ARMS) benefit and for the Prince's Trust, both taking place in September at London's Royal Albert Hall.

Some have suggested that by hiring the Eric Clapton to handle the guitar duties, Waters hoped that David Gilmour's absence would go unnoticed and that fans would buy Waters' claim that he was Pink.

|

Clapton has always been keen to do benefit gigs, and the ARMS show was one of the first all-star charity gigs in rock history. It turned out as particularly meaningful and rewarding in many respects, boasting an incredible line-up of stars playing together as a band, rather than performing individually. Everyone had such a great time that it was decided to take the whole show to America for a further nine dates, with a marvellous spirit and atmosphere binding the musicians together, both on- and offstage.

The ARMS experience and Clapton's renewed enthusiasm for live performance probably were strong reasons for him to confirm his role in what would turn out to be Waters' much stiffer, overly-organised and less 'appropriate' tour in 1984. Eric was as good as his word and indeed joined Roger Waters in England to rehearse for the Pros And Cons tour of England, Europe, and America.

Recording with Waters had been an extremely pleasant experience for Clapton. He had been again in the background, happy to let his own artistic ego fade into somebody else's work, without any pressure to act as a leader or having to make important decisions. But Clapton did make the choice to take part in the tour, and he did it against the advice of manager Roger Forrester, who felt (according to Ray Coleman) that "Clapton was far too established to play what amounted to second fiddle around the world on a project with which neither he nor his music had anything in common. But he loyally followed through, and did European and American dates, having told Waters he would."

In Forrester's view, the move didn't make any sense: why should Clapton suddenly play in someone's backing band after having been his own boss since the early Seventies? However, many people did go and see the shows on the strength of Clapton's name, and were rewarded with some magnificent playing. He had at last found the fire that had been extinguished for so long. Clapton is the first to say that art feeds on personal suffering. It is possible that the continual pain caused by his marital problems--his marriage was in those same days on the verge of collapse--along with the freedom of being out on the road, submerged in a band led by someone else and without any leadership responsibilities, gave him that extra edge.

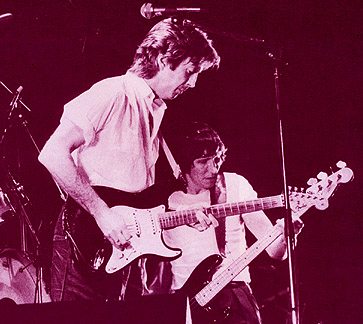

Note Clapton's headphones. Waters' rigidly-structured show required a click track to keep the musicians in sync with the films and other visual elements. This is an example of the kind of thing that made Clapton feel "stifled" during the tour.

|

The band consisted of Roger Waters on bass and lead vocals, Clapton on lead guitar, Tim Renwick on guitar, Michael Kamen on keyboards, Andy Newmark on drums, Mel Collins on sax, Doreen Chanter and Katie Kissoon on backing vocals, and Chris Stainton on keyboards. The stage set-up was quite elaborate, with three huge screens behind the band playing various film sequences and Gerald Scarfe's animations illustrating the music being performed on stage. The show was divided into two parts. The first half consisted of well-known Pink Floyd songs with Eric particularly shining on "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun" and "Money". In the second half, the band performed the entire Pros And Cons album, with Clapton delivering a breathtaking solo on "Sexual Revolution". It was hard to imagination that the man ripping out these notes from his guitar was the same that had been churning out so many pleasant but uninspired solos over the previous few years.

Of course, Clapton's incendiary playing on the tour was positively affected by his increasing recovery from alcohol addiction, and consequently by his new confidence in himself as a man. It's difficult not to notice a close link between the stunning work performed live with Waters and the ripping guitar playing included in some numbers from Clapton's own Behind the Sun. These had already been 'tested' live earlier in 1984 during a short solo tour in which Eric had been the sole guitarist for the first time since the Derek and the Dominos days--a testimony to his maturing self-assuredness as a musician and band leader as he approached his 40th birthday.

Ironically, the man who had left the Yardbirds because he thought they were too commercial found himself in much the same position at this time. His record label (Warner Brothers) turned down much of the Behind the Sun material (while Clapton was on tour with Waters) on the grounds that there were 'not enough singles' included. As Clapton told Q Magazine in 1987, "I suddenly realised that the Peter Pan thing was over. Because just before that Van Morrison had been dropped--mightily dropped--and it rang throughout the industry. I thought if they can drop him they can drop me. There was my mortality staring me in the face."

These events help to better define the context of Clapton's identity and professional path at the time of his association with Roger Waters, as well as the meaning of Pros and Cons to Clapton's later career. According to some, the Pros and Cons tour was probably the weakest career move Clapton ever made. Apart from the lack of responsibilities, the live experience was not too satisfactory, as Forrester had predicted. He hadn't worked as a sideman for fifteen years and he found the live performance with Waters quite demanding both on a musical and personal level, having to fit into the band and to put his ego back into perspective. Clapton didn't like the 'star-system atmosphere' of the show, which he considered bleak and pretentious, and soon got bored of it.

Harry Shapiro writes: "It was more like a travelling five-star hotel, with a mental distance between the players, a sharp contrast with the camaraderie he enjoyed in his own band. Tensions developed. Eric felt lonely, exposed. (...) Musically, as well as socially, Clapton was utterly unsuited to the Waters show. By far the finest musician on the stage, he had no natural place in the theatricality and posturing of it all. For many thousands of genuine music enthusiasts, the show came to life only when Eric played. But he looked uncomfortable, bored, and smoked endlessly to relieve what he saw as the dreariness of the stage show. Fed up from the start, he could hardly wait for the tour to end. The icy coldness of the music and the bad vibes of the touring entourage depressed him."

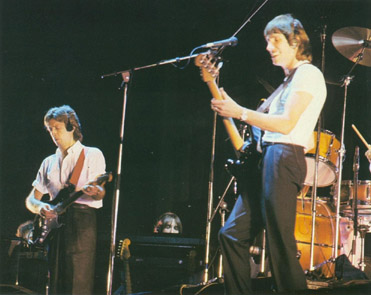

By the end of the 1984 tour, Clapton and Waters found themselves somewhat at odds.

|

Socially, Eric never fit in at all--upscale restaurants had never been his style--and he was glad to leave the tour at the end of July to prepare for his own trip to Australia. Ray Coleman writes: "Once, in Stockholm, at an after-the-show dinner hosted by Waters' record company at a luxury restaurant, a hungry Clapton grew tired of waiting ages for food from obsequious waiters. He said to Nigel Carrol, 'I could do with a Big Mac and French fries'. Carroll left and returned with the fast food fifteen minutes later. Eric enjoyed watching the expressions on the faces of the dinner guests as he tucked into his burger at the table while they still waited for their culinary delights."

Clapton made an impromptu appearance with Bob Dylan and others at Wembley Arena between the European and American legs of Waters' tour. Dylan's show, with its spontaneous jamming and immediate roughness, was especially close to what Clapton had been used to until then, and it clashed, in his experience, to Waters' technological approach on stage. (Dylan even started one number, and then showed Clapton the chords as they went along.) And shortly after completing the 1984 Pros and Cons tour, he also jammed alongside Phil Collins, Peter Gabriel, and Robert Plant at Collins' wedding reception, again seeming to enjoy performing live without any previous rehearsal. These must have been among the main reasons for Clapton not to re-join the band when Waters added more shows to his tour in 1985.

Clapton did take a few notes from his time with Waters. Compared to the slick, conceptual Pros and Cons album, Clapton's latest release (1983's Money and Cigarettes) sounded decidedly accessible and commercial. And Clapton may have adopted some of Waters' careful, methodical production style for Behind the Sun, which shows an increased aesthetic tension in trying to provide a different feeling and a smoother kind of sound.

Waters' obsession for technical perfection and multimedia showmanship might have helped Clapton deal with some of the new directions imposed by the record company, including the shooting of a video. The other significant change was in Clapton's stage show, which soon incorporated a professional lighting system to enhance Clapton's live music; this was done to great effect during "Badge" and "Let It Rain", when hundreds of circular, laser-thin beams of light hit the stage and the audience at varying speeds depending on the tempo of the song.

Clapton's collaboration with Waters also led to some fruitful collaborations with other Pros and Cons bandmates. Tim Renwick joined Clapton's band in February 1985 to play rhythm guitar for the successful Behind The Sun tour. Katie Kissoon was featured regularly as one of Clapton's backing vocalists for another 10 years. Above all, Michael Kamen would become a close friend of Clapton's. He collaborated with Clapton on several motion picture soundtracks. Kamen recalled "Eric got a call from the BBC to do music for Edge of Darkness and he was eager to do it, but needed some help. He didn't know the mechanics of film writing or what to do, realised it was just a guitar-playing score and asked me if I'd be interested. Of course I said I was, because he's my hero--and now my friend, but my hero above everything else"

Coleman tells an anecdote that sums up with importance of Clapton's presence in Waters' band. In late 1984, after seeing Eric "change the colour of the atmosphere" by his playing at one of Waters' shows, Pete Townshend told Eric and said, "Well, it's true, after all these years, Clapton is God". Pete felt stunned at the fact that he'd said it, but he stands by it. "This was Eric making communication from heart to heart. It was divine".

Make your choice, find your voice

After years of delays, Waters finally delivered his opera. Or did he?

From the opening ambient sounds of Madame Antoine's garden to the musical snippets of "The Overture", two things become clear: Ça Ira is going to have ample Waters touches throughout, and it is a full-on opera, not just some half-baked wishful thinking from an old rocker.

|

For those who have listened to it, the first aspect--that Waters' sound that was born during his days with Pink Floyd and continued into his solo career--is both obvious and good. Even folks unfamiliar with Pink Floyd or Roger Waters have commented on the way sound effects (from bird noises to guillotines) are both unexpected and effective. The second aspect--that it is an opera--has, however, produced the opposite situation, with a wide spectrum of opinions on whether or not it is an opera, and following from that, whether or not it's any good. It was this varied interpretation that somehow became stuck in my head, so I abandoned my plan to write a straightforward review and decided to present these various ideas and answer the question: "Is Ça Ira an opera?"

The simple answer to this question is "Yes". In most cases, the people I have asked have happily said "yes", and as if it is so obvious that the question need not be asked. A few others, however, have similarly stated that it is obvious that it isn't an opera. One--who didn't know what she was listening to--went so far as to comment, "I didn't know Andrew Lloyd Webber was releasing something".

It would seem I had a problem. So my first stop on this journey was to answer this seemingly simple question: "What is an opera?" I thought I knew, I must admit. I had a few 'classics' on CD; Il Trovatore, Carmen, The Magic Flute. I have seen a half dozen or so, performed by both the Queensland and Australian Opera Companies. So I'm not tremendously experienced, but probably more experienced than most Roger Waters fans. But I put aside my own convictions and headed for the people who would know: those who did this sort of thing for a living.

First off, let's be general... from Jean Peccei I received so good a summary:

If you're looking for a set of characteristics all of which a work must have to qualify as an opera, you won't find one. Likewise you won't find a set of characteristics which allow you to definitely exclude other works from the 'opera category'. It's even worse than the old philosophical problem of defining a chair. At least with chairs everyone pretty much knows if they're sitting on one. With the major operas in the canon, yes pretty much everyone in the audience agrees that they're at an opera. But go a little outside that and well... then the polemics begin.A combination of music, singing, drama meant to be performed on the stage? A drama set to music? So are musicals.The work although a combination of the above three, has the music as its driving force? I suppose this might set opera off from musicals, but I'm not sure about that. Certainly there is a convention that musicals are often 'listed' by both the composer and the librettist/lyricist (if they are two different people)--Rogers and Hammerstein, Lerner and Lowe. Operas aren't. It's Verdi's Forza del destino, not Verdi and Piave's.Through-composed? So are Evita and Phantom of the Opera.Recitatives instead of dialogue? Both Carmen and The Abduction from the Seraglio have long stretches of dialogue, and everyone agrees they're operas.Profound subject matter and themes? So then where does opera shade off into operetta? Besides I'm not sure that the themes in South Pacific are any less profound than those of Maskerade or even La Fanciulla del West.And defining 'profound themes' is another can of worms which starts getting into the realm of literary criticism as well as aesthetic judgement as does...'Is its music profound and complex?'There seems to be a school of criticism today that for contemporary opera, if the music is 'accessible' and 'melodic', it is by definition not profound. Hence the exclusion of modern musicals from the genre.Performed in opera houses? The Washington Opera is putting on Gershwin's Porgy and Bess, as has La Scala. The Royal Opera House and Chicago Lyric Opera have put on Sweeney Todd. La Scala has even put on West Side Story.Must be sung with operatically trained voices and without amplification? Leonard Bernstein called his Candide a musical for operatically trained voices. I note that the cast for the Ça Ira recording has opera and classical singers in the major roles--Bryn Terfel, Paul Groves, and Ying Huang.However, one British critic after grappling with the issue through an entire article, threw up his hands and said that if an opera house performs the work on the stage, it's an opera. Another said that when it comes right down to it, it's an opera if the composer says it's an opera and not if he/she says it's not.Wikipedia has quite a nice round-up discussion of the various kinds of operas and sub-classes of opera, as well as its history and evolution.

After a little more discussion, Peccei happily added:

"Well, a lot of people on opera groups can get awfully snotty, and I think the fact that Ça Ira was written by someone who's mainly a rock musician is probably enough for them. I think they'd have to have actually heard it before they could make a categorical judgement that it's not an opera. Mind you, when some people say 'This isn't an opera' it often simply means 'This is a bad opera'. I was in the audience for Nixon in China once (which I loved). A man near me hated it and kept saying to his wife, 'This is not an opera!'"

From beginning to end, Ça Ira has everything that is required of an opera.

Finding good comments about Ça Ira has been relatively easy. Around the world, it seems all and sundry are happy to give the positive kind of press that musicians dream about on debut, let alone it's No. 1 status on the US opera charts. So to make it easy, I'll just add some quotes here.

"As readers of these commentaries know, we here at OperaOnline.us have been critical of contemporary composers who have distanced themselves from the melodic style and, instead, opted for the avant-garde rhythms that usually end in things 'onics' as in diatonic, or some variation of it. As we have asked time and again, where are the contemporary composers who can write melody? Roger Waters may seem an unlikely candidate to fit the bill and show 'em what we mean. But then, again, nobody doubts he can write music. What may very well distinguish Waters from all the rest is that he can write melody that is 'unashamedly emotional'." (www.OperaOnline.us)

There has been plenty of positive press for Ça Ira. (MOJO, February 2005)

|

"While Ça Ira may sound like the sort of pretentious nonsense that only rock stars with too much time and money would undertake, it is actually one of the most melodic and memorable modern operas to emerge for years." (Jonathon Wingate)

"It was another eight years before he committed to an English translation of the piece, which is proudly at the accessible end of the operatic scale, with titles such as 'I Want to Be King' and 'France in Disarray'." (Paul Sexton, Sunday Times)

"A far cry from my beloved otto cento operas, but what a rare treat for a modern work. Very accessible and with a melodic and dramatically interesting flow worthy of the name Opera." (John Schweger, Opera-L)

On the negative side, finding opinions has been both hard and easy. Finding negative press has been impossible, although I'm sure it's out there. Finding private criticism has been quite easy. One such e-mail communication I received called the work "Blah Ira(tating)"; another described it as a "turgid mess". A stunning insult! Another negative review, if it could be called that, is the silence that has befallen the various Pink Floyd and Roger Waters e-mail groups that abound on the Net. As expected, most fans won't even consider listening to it, and it seems the few that have are suspiciously quiet in their opinions. I can only assume we'll never know why. In fairness, it should be noted the same goes for fan groups of the performers in Ça Ira. So I'm stumped on that one.

My next port of call was Ça Ira itself. And it was my last port of call as well. If for no other reason, I wasn't about to track down a whole bunch of other "non-operas" to compare it with. So I will happily admit at this point that I'll have to take the negative examples as they come and leave them untested. They very well may be right and I know only too well that anyone's writings, including mine, will have no effect on influencing such an opinion. Folks think what they think and nothing will change it.

From beginning to end, Ça Ira has everything that is required of an opera. Firstly, it has the full orchestra being given a thorough workout for the entire 100+ minutes, with numerous musical highlights apart from the vocalists. A prime example of this is most of "The Commune de Paris", as we are left to imagine 'the plot' unfold.

Secondly, a cast, if not of thousands, at least of scores has us chopping and changing from ring centre to the circus audience and back again throughout. Cleverly constructed, the opera's choruses are the circus audience looking on as the main characters slowly but surely reveal the plot.

The third major piece of the puzzle is the libretto. Sung throughout--with the exception of a young Madame Antoine and a few soldiers' commands--the libretto goes beyond the description of the mundane (as Waters explains in the accompanying documentary) to describe and assess the 'how's and 'why's of the French Revolution. Originally written by Etienne and Nadine Roda-Gil in French, Waters had this translated, then worked into an English version at the insistence of Sony Music. Luckily for us the French version had been recorded so we now have both... but more on that a little later. In the new version, Waters openly admits to taking a few historical liberties for the benefit of artistic expression.

Waters talents as a composer, never in doubt from a fan's perspective, has always been, by popular opinion, continually outclassed by his lyrical ability. In Ça Ira we see this lyrical talent shine yet again, but for me, the music wins out. Without beating the listener over the head, he sets the stage clearly with what happened during the French Revolution, and who was at fault. Yet at the same time he manages to let the listener make up their own mind, even bringing sorrow to the demise of the villains of the piece, and that eternal question we all ask ("what if?") when it all goes wrong.

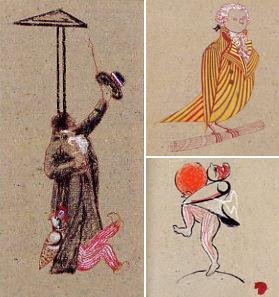

But like Pink Floyd themselves have shown over time, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts when it comes to Ça Ira. It took more than Waters' musical ability and the talents of the likes of Bryn Terfel (Jean-Luc Chaignaud in the French version), Paul Groves, and Ying Huang. Added to the melting pot are the artwork of Nadine Roda-Gil, the orchestration of Rick Wentworth, and the performances of the various musicians involved... and overall you have a perfectly delivered piece.

How complicated it was for Waters to pull off (and why it took 16 years) is best seen in the DVD released with the Deluxe edition. Even for non-opera fans, this film by Adrian Maben (of Live in Pompeii fame) is a worthy purchase in itself, as we get a fascinating insight into Waters' daily professional life as well as glimpses of his private life. Added to that, Maben draws the viewer deeper into Ça Ira itself, through the writing and recording sessions. Just as with Pompeii, this is a film in its own right, not just a "making of" exercise, and one that has you watching it over and over. One of many highlights was an audio glimpse of the demo that Waters presented to President Mitterrand back in 1989. If ever there was a demo I want to hear in full, it is this one. Played on a computer and sung entirely by Waters, in French, I can only imagine how it all must sound... especially the female parts and notes well beyond his range!

The French version, interestingly, is noticeably different, apart from the obvious language difference. First up, the cover announces that Bryn Terfel is not the main vocalist, the duties falling to Jean-Luc Chaignaud. This instantly means we need to compare them, but interestingly, despite being in the same vocal range, comparisons seem unfair. Quite simply, both are unique and each does a fantastic job. While much of the music is the same, there are notable differences in many places. Listening to the French version after hearing the English version countless times, I found myself time and again stopping short of expected words and melodies where there were now changes, some slight, others major. This alone makes owning both worthwhile.

The few people who have heard both seem to favour the version they heard first, which poses many questions. Is it coincidence, or are they both equally good and familiarity wins out in the decision making process? For me, the French version sounds even more like an opera, but that may be a simple bias on my part as I've never been a fan of English language operas, especially translations. The French version however suffers with the loss of the children's English accents, individuals and chorus alike. On the positive side, it makes Ça Ira more 'French', which--considering its content--is a good thing. If push came to shove, however, I would happily sit on the fence! The English version I can readily sing along to. The French version I understand what is happening (because of the English version) and as such, I can just lay back and wallow in the beauty of the vocals and language.

A sampling of Nadine Roda-Gil's art for Ça Ira.

|

Also worthy of note is the artwork. Both in the colours chosen and the images themselves, Nadine Roda-Gil has produced a collection of pieces that stand alone as true works of art. As soon as I saw them I was moved by their beauty and simplicity, and again found myself lamenting the rise of the compact disc (with its tiny booklet) and the insult to artwork it has brought. I already own the three available versions of Ça Ira (the third having the libretto and some artwork on CD-ROM) but will happily snap up some sort of LP version just to have a full scale print of some, if not all, of the images. With the synopsis describing the circus-ring setting, and the opera itself playing through it all, the characters in the artwork come to life, singing, dancing, and dying their way through it all.

So is it an opera? It has the music, instrumentation, and singing. It has the drama. It has, we imagine, the sets and costumes in all the over-the-top ways you expect from opera. It's easy to sing along to in places (especially if you are bilingual), rejoicing in the triumphs and crying in the defeats. It has that fullness that only opera seems to manage when you try to fill a theatre with sound. It is both frightening and delicate. Best of all, like all operas, it is moving, filling the listener with the life-blood that music is. From this humble music fan, to those who do it for a living, Roger Waters has written and recorded a magnificent opera. Better still, it's "bravissimo". Dare I say it... "Encore, Mr. Waters, Encore!"