Features

Choose your own ground

An afternoon with Venetta Fields

When it comes to the women in the world of Pink Floyd there are a few who automatically stand out as being truly influential. Venetta Fields is one of these, for the simple reason that "...we started adding backing vocals to songs that didn't have any. We added some vocals to 'Money' and to a couple of other songs. 'Echoes' was the encore, and Roger said 'why don't you guys make up some parts for 'Echoes' and come back out with us?'"

In March of this year, the Australian Gospel Music Festival had brought Venetta Fields to Toowoomba, my hometown, and Pink Floyd had brought me to Venetta Fields. So, like a suitably idiotic Floyd fan, I was overjoyed at the chance to meet not only someone who had performed with the band, but someone who had influenced their shows as well as the music industry as a whole. Being a perfectly approachable person, the interview with Venetta, going for just over half an hour, was a joy to experience. This was shortly followed by a prime backstage seat to watch and wonder at was happening, and what it must have been like all those years ago.

Between us we soon established that the festival is the biggest in the Southern Hemisphere, covering the three days of the Easter weekend, and taking over a small number of large venues across the usually sleepy country town nestled in the hills inland from the state capital, Brisbane. It soon became apparent that the conversation was also to be a funny one. As I pointed out that the festival was at least the "biggest in Toowoomba", the nervousness was gone (at least from me) and the laughter flowed. In fact the laughter flowed so much that any thought of typing in brackets such moments soon became a pointless task, and would have guaranteed the transcript would have been half as long again.

As the "Ikettes", Venetta Fields, Robbie Montgomery, and Jessie Smith backed up Ike and Tina Turner. |

The history of Pink Floyd and Venetta Fields is complicated, it turns out. So I figured I'd put that off until later. The history of gospel music and Venetta Fields is not so complicated. Having grown up in the United States, Venetta started out, as so many have, singing in church choirs and the like. Her first love, other than singing itself, was and is gospel music. Her talents soon got her noticed and found her standing on stage with the likes of Ike and Tina Turner, The Rolling Stones, and Barbara Streisand. In time, the Blackberries (her group of female backing-vocalists-for-hire) came and went, and Venetta returned to gospel singing, establishing a solo career and backing vocalist career in Australia.

Based on the Gold Coast (Queensland), Venetta soon came to the attention of Australian music legend, John Farnham, whose own career had gone from pop idol in the 60s to superstar in the 80s and since. As a support singer, she was an invaluable member of Farnham's band, but as a solo performer, singing in true gospel style, each night she became a show-stopper with her rendition of "Amazing Grace". From there it was no surprise that she ended up on the Australian Gospel Music Festival's bill, and no surprise she grabbed the invitation with both hands. "[W]hen they asked me to sing gospel, and you know, with John Farnham I did 'Amazing Grace', it was right down my alley. That's when I knew I was in the right place."

If readers are wanting confirmation of this talent, then all they need do is visit Venetta's website and follow the links. Those few downloads all come from her only solo album, At Last, and although a personal milestone and achievement for Venetta, the sales don't do justice to the talent. "I wasn't into promoting and didn't know how to get it actually promoted," Venetta said. "And now with radio stations their play lists are absolutely nailed, and I couldn't really move it anywhere and that was disappointing, but actually getting it out of me... that was a wonderful, wonderful feeling to get it done."

It was obvious that to Venetta, although a pleasure, her career was also simply a job. "Especially for the first ten years you just go to session after session after session after session doing, you know, maybe three or four sessions in a day. You don't really get a chance to get excited". With a resume that reads like a Who's Who of the music world, it is easy to be overawed by it all.

So who really were the Blackberries? To believe Venetta and her recollections of not only joining Pink Floyd for the October 1973 dates in Germany and Vienna (and we have no reason not to believe her) but also her equally clear memory of watching others (Vicki Brown, at least) singing backing vocals before the Blackberries were given the duties, throws an interesting set of questions over that period and its history.

In a nutshell:

"There were three of us first, and sure I named them that. But they really weren't the Blackberries. There was me, Clydie King, and Sherlie Matthews that were actually the Blackberries. This is before Pink Floyd. I asked Sherlie for the name and I took it with me to Humble Pie. Carlena was never a Blackberry. She was there because Clydie couldn't be there any more. So it was me, Clydie, and Billie Barnum-Crotty that went from Humble Pie to Pink Floyd. Clydie couldn't be there anymore so I got Carlena--which was a disaster--and didn't have Billie anymore, but it should have been the other way around."

Venetta states quite clearly that "we were already in London, they were about to do these two dates and they didn't want to send for their girls in America, so they asked Steve Marriott [of Humble Pie] if they could borrow us and that's how it started. Two dates, one in Vienna." She later states that "In the beginning, it was me and Clydie and Billie, in Germany and Vienna for those dates. Then we toured America."

The firmness of Venetta Fields is something, I think, that isn't new. In our interview it was clear that she was in control of her career from beginning to end. Highlighted by her reminiscences of getting the gig with Pink Floyd, Venetta took great pleasure in explaining "they wanted us to see their show before we went out with them, so we went to see them, I forget where that was. Clare Torry sang 'Great Gig in the Sky'. She was there with two more girls. And I noticed they'd sing a song, a couple of songs, then they'd go off stage. And you know, those songs are really, really long. Then they'd come back and sing another song and they'd go off. And I told my girls then and there 'You know when we get on stage, we ain't coming off.'"

What she also remembers clearly is happily confessing boredom at being on stage with the Floyd when The Blackberries first joined the group. This gives way to her brutal honesty in commenting about the Floyd's total lack of talent as musicians. However, to break that image, and get through to the band, it only took a drinking session and singing the blues to break the ice.

For this writer and music collector, a quick check of various books and recordings makes all of the above seem quite straightforward. It is clear from listening to various shows from 1973 and 1974, that 'Money' didn't have backing vocals until the French tour in 1974 (or possibly London in November 1973), and 'Echoes' didn't get backing vocals until the US tour in 1975. It is also clear, with the memories of watching three other singers perform with Pink Floyd before the Blackberries did, that Venetta Fields was not the first.

Putting Venetta's memories together with known concert dates and recorded evidence points to a simple timeline:

March 1973 to June 1973: Three backing singers, possibly Clare Torry and Vicki Brown, most notably singing on "The Great Gig in the Sky" and "Brain Damage"/"Eclipse".

Munich, October 12, 1973: Venetta Fields, Clydie King, and Billie Barnum-Crotty watched the show. Alternately, they may have watched the one of the two London shows in May of 1973, and then actually performed in Germany, though it seems too long a gap from May to October, especially with a June 1973 US tour in between.

Vienna, October 13, 1973: Venetta Fields, Clydie King, and Billie Barnum-Crotty sang.

London, November 4, 1973, and the short French tour in 1974: Venetta Fields, Clydie King, and Billie Barnum-Crotty sang. This is when Clydie King developed the backing vocals for "Money".

From November 1974 onwards: Venetta Fields and Carlena Williams were the two backing vocalists (they are both credited for the 1974 British Winter Tour program). It wasn't until April 1975 that they had impressed Roger enough to warrant an invitation to join them for the encore of "Echoes".

For the bootleg collectors out there, there is pleasure and pain in her words. A few casually put, matter-of-fact statements about what once was. "They would give us a tape at the end of the night if we wanted them but we never kept them."

Sadly, however, all good things come to an end and with the end of the 1975 tour and the recording of Wish You Were Here, the services of the Blackberries were no longer required. As a singing group, Humble Pie's Steve Marriott managed to organise a record deal, however it soon became clear that it was a front for more backroom deals, the Blackberries being the pawns. "They gave me Billy Preston as a producer. It was a shocking, shocking, disappointing experience. And it never got released. I don't think it even got finished. It was just to appease Steve at the time." From there, Venetta took her own career by the throat and has never looked back. "I learned early in my career that a backing singer should never look to go back. So many singers get so upset when they do one or two albums and go on tour but then never do it again. I never did."

Part of that scruff-taking has been to remain very cool indeed; to "cruise" as she says. And it's not hard to see how it is possible for her not only to do it, but do it well. It would seem she has been doing it all her career. "My life was so... never had an accident, never been in any danger. Of course, my Ike and Tina Turner years during the Ku Klux Klan, and our evolving with Martin Luther King, and we had a few little problems and that was something we didn't know any better, we didn't know until we were coming out of it what was happening." A 'few little problems' would have to go down as one of the great understatements of the era.

After the interview, it took a few quick questions and pleads before I found myself in the wings back stage, comfortably seated and ready for the real reason we were all there. Backstage, my first glimpse of professional backstage mayhem was an experience in itself. The afternoon's event was simply a two-hour "Songs of Praise" concert as part of the weekend's festivities. As such, there was a sizeable variety of talent on display, ranging from an 80-member choir to two interpretive dancers. Various solo performers came forward from the choir, and the MC did an admirable job between performances while backstage various versions of panic ensued. This act wasn't there, another not ready, "Where's my costume?", "No that one's mine," and so on. But the show went on, and no doubt from the sold-out audience of 1,500, it was as smooth as silk.

But the backstage panic soon stopped... about ten seconds after Venetta started to sing. She had walked into the throng of madness, completely composed. Most people didn't see her pass, nor probably cared. When she passed me, the "cruising" Venetta Fields from the interview could be seen in that smile... all would be well. So when those first notes were belted out, she yet again proved herself right, and brought to the fore all her experience from the past decades. Backstage, the people turned as one, slowly edging closer to the stage to stand and watch. The audience, who had clapped politely for the half hour before Venetta took the stage, erupted after each number, and back stage, people found themselves breaking the cardinal rule of silence time and again. Even the stage manager joined in!

Armed with a piano player, Ian Macrae, and a mini-disc player that substituted for a band ("I wouldn't want to be with ill-tempered men. They want this or that, they want to cut rehearsals. They are getting less work, but they are lazier. And they are less cooperative as well, so no, I can't be bothered."), Venetta belted her way through a collection of songs from her album, At Last. A triumph to say the least, and a show-stopper to the last, she left the stage with the end notes of "Amazing Grace" drifting off through the audience. Unlike her entrance, when she left the stage, the crowd backstage parted like the Red Sea and clapped her with a respect only given to real talent. I just sat in awe for the whole time. A grand performance indeed!

As for the future, Venetta has no real plans. "Whatever comes along, I'm there for. I'm not trying to reinvent myself. I'm 63 now. I'm just trying to cruise." She spends time teaching singing to the next generation, and hopes that that, along with her experiences, can finally make it to book form for future generations to enjoy. As part of the current generation, I know I am thoroughly enjoying every one of her notes.

Venetta Fields: The Spare Bricks interview (March 27, 2005)

Spare Bricks: Good afternoon and thank you very much on behalf of Spare Bricks, for agreeing to do this.

Venetta Fields: Thank you.

SB: You're here in Toowoomba for the Australian Gospel Music Festival and I believe it's actually one of the biggest Christian music festivals in the world, or Southern Hemisphere?

VF: I don't think it's the biggest in the world. Could very well be Southern Hemisphere.

SB: It's the biggest in Toowoomba.

VF: Yes it is.

SB: How did you come to be involved?

VF: Someone just rang me. The story of my life, somebody just rings you. Someone just rang me and asked if I'd be interested. Then Ken [the promoter] and his wife came down to where I lived [Gold Coast] and we had a discussion about it.

SB: And they obviously know you're keen on Gospel music?

VF: Oh yes, they know my background. It isn't always an all gospel, but yeah, I do do it and it's one of my enjoyable things that I do, being able to sing gospel. Many other people can sing but not too many people can sing gospel.

SB: So would you class yourself as a gospel singer or just as a singer who is happy to be a gospel singer for days like today?

VF: Yes, not as solely a gospel singer. But basically a singer. Very versatile. Gospel is one of my fortes and one of my things I really, really love to do. Gospel is in the forefront, but I'm just a singer. I don't actually want to stereotype myself or put myself in a box.

SB: What role do you think gospel music plays in the secular world?

VF: It has been growing since I was a little girl, and had really taken a good foothold in the secular world. I guess with all the things that are happening in the world today people are really listening more. It wasn't really that promoted. It was basically cultural, gospel, and black-orientated. But now it's got a wide realm. It's very popular in America. When I started going back 10-12 years ago it was absolutely on fire, with gospel shows, as well as television programs, as well as more radio coverage. Los Angeles has got an all-gospel station that plays just gospel. You hear many choirs and groups and things which you didn't have a chance to do before. Plus there's another Christian area which is even bigger because it takes over basically the whole world, that's not so much gospel, but basically Christian music. I'd love to write one of those good old Christian songs, not gospel so much, but one of those really... they put it up on the screen in church to sing along and it's got those simple melodies. That's what I'd like to do. But it has grown a lot. Even in Australia it has really grown as well. So it's getting quite popular. I enjoy it. I don't sing as much of it as I'd like to but I was happy that Australia loved it. I had no idea what Australia was into other than it's regular pop music. So when they asked me to sing gospel, and you know, with John Farnham I did "Amazing Grace", it was right down my alley. That's when I knew I was in the right place.

SB: You've never been tempted to go back to the States, considering how big it is?

VF: No, no. Competition is too fierce over there as well. I'd like to hear more of it. Australia doesn't play it a lot. It's not exposed as much over here. I'd like to hear more of it. I used to go to those conventions and choirs and oh, it was even more amazing then than now.

SB: It's just a lot easier living in Australia.

VF: Well, after I had my career at home I said "I need to go somewhere, do something different and make it easy on myself" and Australia was it.

Venetta Fields (left) with Aretha Franklin. |

SB: Apart from artists like Aretha Franklin or Al Green, those sorts, do you feel that Gospel music has a future both as a religious expression and a commercial entity?

VF: Oh yeah, definitely. It's growing from a religious experience to a spiritual experience, and on to commerciality and that's what I really liken it to in religion, because I'm not in organised religion. It's taken on a very, very spiritualised realm which I'm glad it really does because it's individual how you feel about it. It's an individual thing. I was more into our culture in the old days because that's all we had and that's what we had to do to get ourselves adhesive. But now as you say it's spreading commercially so it's not really, in my opinion, for what I'd like it to be, I'd like it to be more spiritual than actually religious.

SB: Do you see there is a difference in the pressure between being a solo artist and a backing vocalist?

VF: Oh, yes. Lots.

SB: And is that pressure worth it? Is it a good kind of pressure?

VF: Yes it is, that's why we'd we rather be out there singing our songs. Coming up as a singer in the church I was always in groups and choirs. When I was in a group, we shared solos and backing vocals. I am a very group-oriented person, so when my backing vocal career came I absolutely loved it. I liked to get right behind the artist so their light shines on you a little bit, and you give them the support they need. Make yourself indispensable, make yourself have a certain sound that that artist really, really needs and depends on. Basically that's where my head always was. I spent ten years doing it. Before I recorded my cd, I related the making of it to baking a cake, so it wouldn't scare me so much. I said, "Venetta, you've sung with so many people and they've made so many varieties of cakes. You've got so many recipes I bet you could make your own cake." So I did. That made it less frightening, and it seemed much less out-of-reach.

SB: And has the album gone well?

VF: No, because I wasn't into promoting and didn't know how to get it actually promoted. And now with radio stations their play lists are absolutely nailed, and I couldn't really move it anywhere and that was disappointing, but actually getting it out of me... that was a wonderful, wonderful feeling to get it done. The disappointment was the promotion of it.

SB: But it was still worth it?

VF: Oh, definitely.

SB: And it is worth listening to.

VF: Yes it is worth listening to, it still works as a record.

SB: That was a comment, not a question.

VF: Not in the early days. I didn't know who everybody really was because I wasn't a record listener. I didn't buy records or listen to them, but as I was in it more you knew who the artists were. I sang for the Rolling Stones and Aretha Franklin and Barbara Streisand, but no, not really.

SB: It was just a job? But a good job.

VF: It was a job. Especially for the first ten years you just go to session after session after session after session doing, you know, maybe three or four sessions in a day. You don't really get a chance to get excited, because you never... you might hear your song becomes number one on the radio, but you aren't into that person's career. You just hear yourself on the radio--"Oh, that was a hit"--and you're onto your next session. So not really. Not until I'd moved here did I realise what I'd done. You just don't know what you're doing. It's just happening so fast until you slow down and relax and look back behind you and say "Wow". And now when I read my resume, or when someone is reading my resume before they introduce me, when I hear my resume now I think to myself, "This person is really old or dead. The things that you've done, my God, aren't you tired?" I loved being a backing vocalist because the pressure was off, but I could see what was happening to them.

SB: You must have some great stories about the Rolling Stones and Ike and Tine Turner and all of them.

VF: Yes I do, but everybody wants to listen to the dirt. There was no dirt, I swear. My life was so... never had an accident, never been in any danger. Of course, my Ike and Tina Turner years during the Ku Klux Klan, and our evolving with Martin Luther King, and we had a few little problems and that was something we didn't know any better, we didn't know until we were coming out of it what was happening. So I was never in a place where there was anything worth talking about. A few things, but not really. When I was with one of my friends, my colleague out here with Neil Diamond, and we were together and she was saying she went with one band and all the things that were happening. And I said "What? Really? That never happened to me".

SB: Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

VF: That was a very good thing. After the night was over I didn't go into the bars and stuff. I went to my room to unwind and come down. I was never one to drink heavy and stay out and, you know, party after the party. I didn't like people to hang around after that was over so I was always in my room. I was just telling my keyboard player about Farnham and the grand piano. It would take him a while to come down so he would go to the hotel most times and sing at the bar and have us all come down and drink and sing. I didn't; I was in my room and he knew I loved Moet champagne. We had it almost every night. He would bribe me with a bottle of Moet if I would come down to the bar and sing. I'd stay there about a half hour and we all sang any kind of song which is absolutely such a wonderful time. And then I'd go to bed. And another thing I didn't realise 'til later was girls... like the band went out after the gig to pick up girls, but girls didn't. Because you're in the middle of a city and you don't know anybody. You can't go off with any man or anything, you really can't. So we were always saying the boys would go out and come back with many, many tales, and ailments.

SB: In the past, specifically to do with Pink Floyd, yourself and Carlena Williams were known as the Blackberries?

VF: There were three of us first, and sure I named them that. But they really weren't the Blackberries. There was me, Clydie King, and Sherlie Matthews that were actually the Blackberries.

SB: This is before you met Pink Floyd?

VF: This is before Pink Floyd. I asked Sherlie for the name and I took it with me to Humble Pie. Carlena was never a Blackberry. She was there because Clydie couldn't be there any more. So it was me, Clydie, and Billie Barnum-Crotty that went from Humble Pie to Pink Floyd. Clydie couldn't be there anymore so I got Carlena--which was a disaster--and didn't have Billie anymore, but it should have been the other way around. "Great Gig in the Sky", when I was with Clydie and Billie was a solo, but when I only had two girls, I divided that solo between Carlena and myself.

SB: So, from memory, in late 1972 David Gilmour invited you along to shows. [Editor's Note: Here and elsewhere during the interview, both Venetta and Christopher seem to have struggled with pinning down the actual dates. For a reconstruction of the proper timeline, please see the article above.]

VF: We were already in London, they were about to do these two dates and they didn't want to send for their girls in America, so they asked Steve Marriott if they could borrow us and that's how it started. Two dates, one in Vienna.

SB: The three of you?

VF: The three of us. Me and Billie and Clydie were with Humble Pie. When we got to the Floyd, Clydie wasn't with us at all.

SB: So you and Billie sang in Vienna?

VF: No, no.

SB: In Germany?

VF: In the beginning, it was me and Clydie and Billie, in Germany and Vienna for those dates. Then we toured America. Clydie made up the backing vocals for "Money" because there weren't any vocals for "Money". Me, Billie, and Clydie. Towards the end of Humble Pie, Clydie got sick and then when Pink Floyd called us again, I got Carlena to go out. They only wanted two girls.

SB: And that was in mid '73.

VF: Yeah, '73 and '74. We recorded Wish You Were Here.

SB: What sort of input did yourself and Billie and Carlena and Clydie have into what you sang?

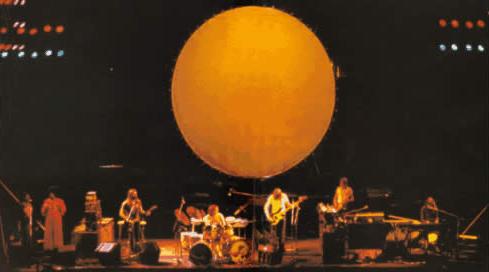

Venetta Williams (far left) and Carlena Williams accompany Pink Floyd in 1974 or '75. |

VF: When Steve Mariott reluctantly agreed to lend us out to Pink Floyd for two dates, David Gilmour brought the cassette of Dark Side of the Moon over to our motel. We were playing cards in a little motel and we laughed. I had never heard of them or their music. We laughed. A bunch of little "oooh's", and minor keys, and really strange. We thought 'what is this?'. We cracked up. Then we saw them. They wanted us to see their show before we went out with them, so we went to see them, I forget where that was. Clare Torry sang "Great Gig in the Sky". She was there with two more girls. And I noticed they'd sing a song, a couple of songs, then they'd go off stage. And you know, those songs are really, really long. Then they'd come back and sing another song and they'd go off. And I told my girls then and there "you know when we get on stage, we ain't coming off." And again, that night, maybe the first night too we did it, it was absolutely boring, because I'd never slowed down like that. But I was mesmerised by the type of show that they had. All the state-of-the-art equipment, and the screen and the airplane and all that. But the music itself was absolutely shocking, the musicians were absolutely terrible. But the spirit told me "you are out there for a reason" and I didn't even know that Dark Side of the Moon had been in the charts. I'm in the business, but I didn't know a thing. So then we started adding backing vocals to songs that didn't have any. We added some vocals to "Money" and to a couple of other songs. "Echoes" was the encore, and Roger said "why don't you guys make up some parts for 'Echoes' and come back out with us?" So they loved it; they really, really did.

SB: I was going to ask if they said "do this, this, and this" but obviously there was a mutual respect.

VF: It started out that way. Roger was very stand-offish, and the other two as well. Dave was the only one that was friendly. We spent a lot of time with Dave; even before we started singing with them, we used to go to his farm. David Gilmour and Steven [Marriott] and Jerry [Shirley] and Dave [Clempson] were all friends, so we use to spend weekends out at Dave's place. He was the one that actually brought us in.

The first night, in Vienna, doing our very first gig, we were very stiff sounding. We didn't put in any extra vocal parts at that point in time. They put us up in a place that was like a beautiful castle, with rooms that were huge with eighty- or ninety-foot ceilings. The restaurant must have been left open for us because we were very late coming in, but we had a big entourage. Everybody was there, I think part of the crew as well, and we were drinking and talking. And the next thing we knew we were all under the tables with bottles of wine singing "Summertime". That broke the ice. Roger was down, Nick was down, and Rick, we were all very merry. From that time on we never really had a problem anymore. Not that we had one before, but it sort of settled it down because they were a bit stiff.

SB: Obviously you were very impressed with the stage?

VF: Oh, yeah. It was amazing. And the quadraphonic sound was amazing too. They had all the state-of-the-art equipment way before it came on the market commercially. Dave's guitar pad had about thirty-six little things you'd step on to do thirty-six little different sounds.

SB: Once you got used to Dark Side of the Moon could you appreciate it? Do you listen to it now?

VF: I love it. I'm thankful I got it in my head to appreciate it. I loved the experience of it as well.

SB: Do you have recordings of your performances with them?

VF: No, nothing live. We did have them. They would give us a tape at the end of the night if we wanted them but we never kept them, or through the years they just got lost.

SB: How much did you see the band change? In '73 they were the quiet English progressive rock band. By '75 they were "Pink Floyd, The Greatest Band in the World". Dark Side of the Moon had wiped the board. They often talked about how the success of Dark Side of the Moon ruined them in that respect as they had finally achieved the money and fame and success. Did you see those changes in them?

VF: Yes. I was in two rock 'n' roll bands, Humble Pie and Pink Floyd, and they were total opposites. I saw the managers hype Humble Pie up so much to let them get famous, and then the American managers stole everything. Pink Floyd told their manager what to do. They were very well-educated, very intellectual. They kept all their money. They were very, very smart. It takes a lot to keep control. They kept it under very strict control and I really admire them for that.

SB: When you got to the studio for Wish You Were Here in 1975, and you'd obviously been singing a lot of the album already so you knew it quite well.

VF: We just went in for one song.

SB: Oh yes, you were only there for a day or two. Did you notice, were they different from what they were on tour? Were they strained?

VF: When we got in for our singing, we were with Roger only. Other parts had already been done so I was never there for the making of that. It was just me, and the girls and Roger and the backing track. Syd Barrett did come in and there was a very weird vibe there for a while because they hadn't seen him in years. It took about and hour-and-a-half and then it was over.

SB: And that was all very normal?

VF: Yeah, there was no problem.

SB: From the recording sessions can you remember things like Roger saying "we want you to do this, this, and this?" Or did Roger say "you know how we developed it on tour?" Or did you just have to make it up?

VF: Make it up like we always do. It was no big deal.

SB: He had full faith in your talent?

VF: Most producer--because they knew we were coming in--would say "come in and save my ass". They knew what we did, they just let us do it.

SB: Among fans, it's been thought that Rick and David were the musical ones and Nick and Roger were the conceptual ones.

VF: Roger was the conceptual one... terrible musician. I thought Rick and Nick were absolutely shocking musicians. David Gilmour was a brilliant musician.

SB: Were you invited to sing on Animals and The Wall?

VF: No, not The Wall, that was afterwards. I was invited to the premier of the movie of The Wall and David was in Los Angeles. He gave me an album, but you know what, I left it at his house. But we went to the premiere of the movie.

SB: In touring '74 and '75, you were singing songs that ended up on Animals.

VF: I didn't know that. I didn't keep up with the music.

SB: Does it bother you, because they had backing vocals on The Wall?

VF: I learned early in my career that a backing singer should never look to go back. So many singers get so upset when they do one or two albums and go on tour but then never do it again. I never did. Your sound changes. I have such a strong sound, and the act might want to try something different. So I was never worried about them not calling me back.

SB: So you weren't worried when they toured in '87 or '94?

VF: Never.

SB: Have you heard Dark Side of the Moon from the 1994 tour video?

VF: Yes, I've seen it.

SB: And could you say "I did that, I did that"?

VF: Absolutely. Plus, they were singing parts that we made up.

SB: And you're obviously proud of that.

VF: Absolutely.

SB: Do you have any comment about Roger's assessment that he was the main creative force behind the Floyd?

VF: I think they were both equal. Roger is very smart and very intelligent, but he needed Dave to bring it home, with his creative talent. He's just a really, really talented musician. It took both of them to bring it to the fore. They were thinking together. They were on the same page. Each of them had their own jobs to do.

SB: Do you have any contact with Carlena Williams anymore?

VF: No. I haven't seen her since, I think I went home about '84, something like that. She came to a barbecue that my friends gave me, but I haven't seen or heard from her since.

SB: Is there a story that goes with the end of the Blackberries?

VF: During the Blackberries time, Steve Marriott got us a contract with A&M. By this time, Dee Anthony was Humble Pie's manager and they just did it to appease him. So when it actually came to do it the record company wasn't much interested in it. The Pie were, but by that time they were in London having their own problems. They gave me Billy Preston as a producer. It was a shocking, shocking, disappointing experience. And it never got released. I don't think it even got finished. It was just to appease Steve at the time. We weren't strong enough to make it happen. We just broke up. I went on with my session work. Back to my Steely Dans and my Boz Skaggs. I went on from there as a backing vocalist.

Venetta Fields, in her stage costume for the Australian Gospel Music Festival. |

SB: What have you got planned for today?

VF: I've got a few gospel songs on my CD. Just inspirational gospel songs for a nice, light afternoon.

SB: Are you going to do a rendition of "Amazing Grace"?

VF: Yes, it's on my CD. I can't get away from it. Sometimes I do corporate work and I can't get away from it.

SB: Did you choose that one?

VF: I chose it. Because again, Australia has heard me sing it throughout my career here with Farnham so I figured they'd want me to at least put it on CD. So I did. They can use it for whatever reason, somebody's funeral, somebody's wedding, whatever.

SB: Have you a band here with you today?

VF: No, I've just got my keyboard player and my music in a box; a mini disc. I usually travel with that now because they don't want to have to pay for a band, to pay a lot of money for really good musicians.

SB: Does that limit you?

VF: Yes, in some ways, but you sort of get used to it after a while, but all your music is still there. It's just in a box. It took me a while to get used to. But now I wouldn't have it any other way. I wouldn't want to be with ill-tempered musicians. They want this or that, they want to cut rehearsals. They are getting less work, but they are lazier. And they are less cooperative as well, so no, I can't be bothered. I can get away with it at this late stage of my career. If I was still 30, 40, 50, I'd think about it, but at this time, I don't care! I'm glad I got through it with you, but now I don't have to have you.

SB: And today's a one-off? Or are you currently planning some shows in South East Queensland?

VF: No, this is just a one-off.

SB: So what is coming up in your immediate future?

VF: I don't know, actually. I have been in the process of writing a book for about two years. It comes and goes. That's been a struggle, getting a publisher and all of that. No, I don't have any immediate plans. Whatever comes along I'm there for. I'm not trying to reinvent myself. I'm 63 now. I'm just trying to cruise. The Crown Casino... I'll do some gospel things there every now and then, but no, I don't really want to hear it like that because it takes a lot to reinvent yourself. I teach and that's what I really enjoy, teaching. I teach, giving this information out. I'm teaching my legacies, so that's what I really enjoy doing.

SB: Well therefore you must have some sort of advice for people who are only in their teens or their twenties.

VF: It takes dedication, hard work, and commitment. And responsibility really. And the first thing you need is talent. That's the first thing.

SB: Which is why I'm asking the questions instead of answering them.

VF: You need talent. A good ear. Learn an instrument if you can. If you are just a singer, learn an instrument so you can learn your chords and notes. Dedicated. You have to be dedicated. You have to be on time. You have to create your certain style and know the sound of your voice. Find that early... a lot of singers even if they have got a song out today, they haven't found that identity so you won't hear from them any more. They don't have an identity with their sound or their compositions. Those are the things. But you know what? I don't know what you are going to need now because music is so watered down from what we had. My suggestions don't really apply to the next generation.

SB: Anything else you'd like to tell us on life, the universe, and everything?

VF: No, I think I've said about enough. I hope I haven't discouraged anybody.

SB: No, it's been wonderful. I do have one final question.

VF: What's that?

SB: One of our writers would like to know what's your favourite colour.

VF: Red. Red, I love no-bullshit red! Red means you are definitely ready and let's go and do it.

Atom Heart Mother (1970) |

It was Wright who most famously explored his feelings about groupie relationships in "Summer '68" from Atom Heart Mother. The lyrics show Wright's remorse over such infidelity (he was married to Juliette Gale Wright from 1964 to 1984, a period that obviously included the titular 1968 as well as 1970, when the song was recorded and released).

The first verse impresses upon the listener just how brief and transitory these relationships were--he had only just met the woman "six hours ago", and acknowledges that their parting comes quickly on the heels of their introduction ("We say goodbye before we said hello"). But what is most striking is the speaker's desperation to make some kind of emotional connection with this groupie. The opening lines form a polite invitation: "Would you like to say something before you leave? Perhaps you'd care to state exactly how you feel." The repetitive chorus is even more blunt, and all the more plaintive: "I would like to know... how do you feel?"

Was Wright remorseful for using these women for sex, or did he feel used himself? Was he feeling guilty about seeking solace in the arms of nameless woman after nameless woman, when what he really longed for was emotional contact rather than mere physical companionship? The lack of meaningful communication and connection between the speaker and the woman is quite clear. "Not a single word was said", either as they were meeting, in a room too loud to allow for conversation, or as they parted ways, slinking off after an illicit rendezvous. He shows no real affection for her ("I hardly even like you, I shouldn't even care at all"), and their 'lovemaking' seemed empty, meaningless, rote ("Occasionally you showed a smile, but what was the need?"). He admits that this encounter is just one in a string of similar experiences for both himself ("Tomorrow brings another town, another girl like you") and for her.

Worst of all, the experience leaves the speaker feeling emptier and more alone than he felt before he met the woman. He feels as though he has "lost a bloody year" of his life, feels symbolically cold (isolated, alone) despite the room's warmth, and wishes he was elsewhere, in a happier place with his true friends. Perhaps the most telling line is the last one, in which he states "I've had enough for one day".

[I have chosen to ignore the cryptic lines "Goodbye to you/Charlotte Pringle's due" for several reasons. First, although these are the lyrics printed in the 'official' CD booklet, there is no guarantee that they were transcribed by or approved by Wright himself. (Some hear the lyric as "Charlotte Pringles too", for example, and I've seen several other transcriptions.) Second, the internet abounds with speculation as to who this mysterious Charlotte Pringle was, though the common assumption is that this is the name of a specific groupie. And finally, parsing the lyric isn't entirely straightforward: is it a possessive (i.e. that which is due to Charlotte Pringle), or perhaps a contraction (as in "Charlotte Pringle is due")? Solving this mystery will doubtless shed great light on the misunderstood songwriting genius that is Rick Wright, but until he comes forth with a statement about what he singing, I think I'll leave the guesswork to others.]

One can only imagine what Juliette Gale Wright must have thought about "Summer '68". She had performed with early incarnations of Pink Floyd and had toured with the band, so she would have been well-acquainted the rock 'n' roll culture and the entourage of groupies that apparently followed the Floyd during the Underground days. I assume that she had some knowledge of her husband's dalliances, and perhaps "Summer '68" was Rick's way of purging his guilty conscience, or telling his wife what every jilted woman wants to hear: 'She meant nothing to me'.

Obscured by Clouds (1972) |

Now let's turn our attention to Wright's other lyrical statement on the subject of fleeting sexual encounters, "Stay" from Obscured by Clouds. The song is credited to Wright and Waters jointly, though Wright is listed first. It is not known precisely which wrote the lyrics and which wrote the music, or whether it was perhaps a collaborative effort on both counts. The fact that Wright sings the lead vocal suggests that he was the lyricist, as was the group's general M.O. in the late '60s and early '70s. ("Us and Them", however, is a ready example of a song in which Wright sings a Waters lyric set to Wright's music, with writing credit listed the same way). For the purposes of simplicity, I'm assuming that these are basically Wright's lyrics.

"Stay" is often interpreted as a statement on the fleeting nature of romantic relationships, which it certainly is. But the line "Rack my brain and to try to remember your name" tells us that the speaker is without a doubt not well-acquainted with his lady companion. The song simply cannot describe the breakup of a pair of longtime lovers; this is a one-night stand.

Whereas "Summer '68" focuses entirely on the 'morning after', and is something of a snapshot of the moment in which the man and the woman awkwardly part company, "Stay" is a more complete exercise in storytelling. (I like to think of this as being the influence of Roger Waters, who was emerging as the more sophisticated songwriter by the time Obscured by Clouds was recorded.) The first verse represents the seduction, while the second verse represents the awkward moment in which two strangers find themselves waking up together, as described in "Summer '68".

In the first verse, the speaker (presumably the man, though the lyrics are decidedly gender-neutral) opens a bottle of wine and invites his potential partner to "Stay and help [him] to end the day". He turns on the charm, telling her that he wants to get to know her ("I want to find what lies behind those eyes"). Like the speaker in "Summer '68", this man seems to be seeking companionship to ease his loneliness. Perhaps he has learned from earlier escapades that getting to know the woman will make this encounter more satisfying to him on an emotional level.

In the second verse, the man awakes the next morning and is "surprised to find [the woman] by his side". His thoughts are no longer clouded by lust and alcohol, and instead he finds himself viewing her through his "morning eyes". We might surmise that his surprise is a pleasant one--perhaps he is used to having his groupies and other temporary lovers slink off in the middle of the night, and he is glad that this one has stayed with him through the night. But just as his inability to remember the woman's name shows that this is yet another fleeting affair, so does his struggle "to find the words to tell [her] goodbye" suggest that he really just wants to be rid of her. The mood is again awkward and embarrassing, as both are faced with the stark fact that they are simply using one another.

Particularly poetic are the couplets that close each verse. During the seduction phase, the "midnight blue" of the night sky is described as "burning gold", a warm, romantic image in stark contrast to the "yellow moon" that is "growing cold" (harkening back to the 'cold' mentioned in "Summer '68, and foreshadowing the emotional chill between the lovers the next morning). On the following "new born day", that same midnight blue has "turned to grey", indicating that what was once beautiful, warm, and inviting has become dull and lifeless. The color imagery not only clearly defines that period of time in which each verse takes place, but also encapsulates the song's emotional content.

[The final couplet of the second verse also contains the somewhat mysterious phrase "morning dues", as published in the 1995 remaster CD booklet. Perhaps it is better transcribed as "morning dews", thus going along with the idea of the "new born day". But if the word was indeed "dues", that raises some questions. Taken in the context of "Summer '68" and the line about "Charlotte Pringle's due", might we surmise that Wright felt some obligation toward the groupies he slept with? Did he feel that they were 'due' some measure of respect and polite hospitality? Was there an unwritten code that groupies were 'paid' for their services with a little kindness and consideration afterwards? Was this the part of the encounter that Wright found the most uncomfortable? Again, I don't want to engage in too much speculation, but it is certainly something to think about.]

Both "Stay" and "Summer '68" are easily-overlooked songs by an easily-overlooked member of the band on easily-overlooked albums, but they stand up to close scrutiny. It took a lot of courage for Rick Wright to have put such a delicate subject on display in this way. His frankness and honesty reveals a side of the world of "sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll" that most bands would never explore on record.