Spot the Player

Nick Mason and the Ballad of Mike and Carla

Nick Mason's Fictitious Sports has a reputation as being quite bad--or at the very least quite unlike the Floyd. Many fans don't even consider it a 'proper' Floyd solo project. The music was all written by jazz keyboardist and arranger Carla Bley, and was recorded at Bley's New York studio by Bley's big band (with Mason sitting in on drums). As is typical of Bley's music, the songs are brash, quirky, and humorous... and not at all what anyone was expecting from a member of Pink Floyd.

A portion of the Gorey-inspired cover art for The Hapless Child.

|

Nick Mason's association with Carla Bley and her bandmates goes well beyond this album. He first worked with them in early 1976 doing a little engineering on some sessions at Britannia Row Studios for an album called The Hapless Child. Avant garde jazz composer and trumpeter Michael Mantler had put a number of poems by Edward Gorey to music, and although he does not perform on the album, he was intimately involved with the recordings, which were produced by his wife, Carla Bley. The musicians included Bley on piano and synthesizer, as well as bassist Steve Swallow and notable jazz drummer (and sometime Bley collaborator) Jack DeJohnette.

Providing vocals on the album was Robert Wyatt, formerly of Soft Machine. Mason, of course, had met Wyatt during the Floyd's early days, when the two bands had shared bills. In 1973, Wyatt was crippled after falling out of a window, ending his career as a drummer. (Pink Floyd even played two benefit concerts--along with Soft Machine--to help raise money for Wyatt's medical bills.) Wyatt then embarked upon a career as a keyboardist and singer, recording Rock Bottom in 1974 and Ruth is Stranger Than Richard in 1975, both of which saw Mason in the studio as a producer. Mason had also played drums in Wyatt's band at a comeback concert at London's Theatre Royal in September 1974, and appeared on Top of the Pops with Wyatt a week later, miming to Wyatt's "I'm a Believer" single (which Mason had produced).

Mason and Robert Wyatt mime their way through "I'm a Believer" on Top of the Pops in 1974.

|

The songs on The Hapless Child sound like many other Michael Mantler compositions: somber, meandering melodies that slowly unfold over long, drawn-out chords. Mantler is a trumpet player, and often writes music for trumpet or flugelhorn, but The Hapless Child has no horns at all. The bulk of the recording was done at Mantler and Bley's Grog Kill Studio in Willow, New York, while Wyatt's vocals and other work had been done with a mobile studio at Wyatt's home. Finally, in January 1976 Mason was brought in to do some remixing at Britannia Row, which was still a fairly new enterprise for the Floyds. As Mason recalls, "I think Mike wanted some help to try and smooth the record out. I guess the original multi-tracks were done at Grog Kill, and it was very jazzy sounding (i.e. rather too 'live' for what he wanted), so I did some remixes as far as I remember to try and tidy up some of the sounds. I remember Jack DeJohnette was the drummer, who was sensational, but he had a particularly live sound to the bass drum that needed reduction (in my opinion) and I suspect we played with the vocals a little." In fact, Mason himself can be heard as one of the incidental voices on the album.

Mason hit it off quite well with both Mantler and Bley. After Mason wrapped up his work on The Wall with Pink Floyd, he began to consider doing some kind of solo project. "I had a deal to do an album, and it had to be recorded out of the U.K.," Mason remembers. "I had already worked with Carla and Mike, and talked to them about doing something together. Carla had some songs [already written], and added more specifically for this joint effort."

Nick Mason's Fictitious Sports

|

Fictitious Sports was recorded at Grog Kill in November and December 1979, and since Bley had scored her compositions for a jazz-rock ensemble with horns, the band was made up almost entirely of players from the Carla Bley Band. The group was going through a bit of a transitional phase, with Gary Windo (tenor sax), Howard Johnson (tuba), and Terry Adams (piano) on their way out. Gary Valente was new to the group, replacing Roswell Rudd on trombone, and was to become one of Bley's favorite soloists. (One listen to his explosive playing on "I'm a Mineralist" and you can easily hear why.) Carlos Ward, Vincent Chancey, and Earl McIntyre, who provide 'additional voices' on the album, appeared on Bley Band recordings and tours both before and after Fictitious Sports. Another of these 'additional voices' was that of D. Sharpe, Bley's regular drummer. Bassist Steve Swallow had joined the group in 1978 (replacing Hugh Hopper of Soft Machine fame, who had toured with the Bley Band in 1977), and had been played with Mantler and Bley as early as 1975 on The Hapless Child.

Bley's band did not typically feature a guitarist, so she brought in Chris Spedding, who had played on Mantler's 1977 Silence album, along with Bley and Wyatt. (Spedding had also recorded with Cream's Jack Bruce, who will enter the story a little later.) Wyatt contributed vocals, as did a young R&B singer named Karen Kraft, who had been brought to Bley's attention by Spedding. "Nick and Carla informed me that they didn't want me to sing in my natural voice, but wanted me to sing like I looked," Kraft told Floyd fan Craig Bailey. "I was then and still am a very petite, blueish-eyed blonde with a very big, deep, booming, quasi-black singing voice. Nick and Carla were into the dichotomy of it all."

Fictitious Sports is not what you would expect from a member of Pink Floyd, but it isn't exactly what you would expect from Carla Bley, either. Her music is often dramatic and adventurous, and while her band often used humor to great effect (especially on stage), the playful quirkiness of songs like "Boo to You Too", "Wervin'", or "I Was Wrong" would have been somewhat out-of-place on other Bley records. The majority of Bley's compositions are instrumentals, which makes the inclusion of a lyric on every Fictitious Sports track quite unusual. The jocular interplay between the lead singer and the rest of the group on "Can't Get My Motor to Start" recalls later Bley compositions such as "The Lone Arranger" or "Very Very Simple".

"Hot River" was reportedly conceived as a sort of homage to Mason's Floydian background, complete with a soaring, guitar-hero solo at the end (though we would never expect Roger Waters to rip into a lovely bass solo the way Steve Swallow does). "Do Ya?" is musically more similar to a Michael Mantler composition than to Bley's style, and with Wyatt's vocal it might be mistaken for an outtake from The Hapless Child. And Mason admits that "I'm a Mineralist", with its minimalist arrangement and lyrical jabs at composers such as Philip Glass and Erik Satie, was influenced by Mantler's own minimalist leanings as a composer and arranger.

"[The album cover] is a great idea and produced some wonderful ephemera, such as a square tennis ball and round dice, which I still have." -- Nick Mason

|

Mason recalls: "It was 'my ' album in terms of ownership; i.e. it was under my EMI deal, and I think everyone understood and was happy with this. For Carla it was another exercise in her endless appetite for producing music, but I certainly had control of the sleeve, etc." As such, Storm Thorgerson and Hipgnosis were brought in to do the cover, which is supposed to show an aerial view of a playing field for an imaginary athletic event--a fictitious sport. (And from the looks of the playing field, it would probably be a rather complex sport at that.) The inner sleeve featured a photo of two Hipgnosis-designed items along the same line: a square tennis ball and a pair of round dice.

Nonetheless, most fans seem to recognize that this was a Carla Bley project, rather than a 'proper' Nick Mason project. But what would you expect from a 'solo artist' who neither writes songs nor sings them? "Of course it's not a solo album, per se--it's me solo from the Floyd," Mason says. "I loved the process of making it, and it had the additional benefit of reaching a wider audience for Carla rather than ECM, who I think were her label at the time. Didn't really work, but it was a little un-Floyd-like!"

Though recorded in 1979 and mixed in 1980, Fictitious Sports was not released until May 1981, and reached number 170 on the charts. "I'm sure its it's far too weird to appeal to Floyd fans, really, but I had the opportunity to do something, and I really enjoyed doing it. I never expected or wanted a solo career. My view is that if people like it, it's my solo album. If they don't, it's Carla and Mike's."

Michael Mantler - Something There (1983)

|

The relative failure of Fictitious Sports did not put a damper on further collaborations between Mason and Bley. In 1982, Mason played drums on Michael Mantler's Something There album, with a band that included Mantler, Bley, bassist Steve Swallow, and jazz guitarist Mike Stern. Mason was only minimally involved in Alan Parker's film adaptation of The Wall, which gave him plenty of free time for the sessions. The original recording took place again at Grog Kill Studio, though members the London Symphony Orchestra were hired to provide strings for parts of the album, and these were recorded at Britannia Row Studios, with Nick Griffiths engineering.

The music is something of a departure from the lighthearted jazz-rock of Fictitious Sports, and is often reminiscent of the orchestral arrangements found on many of Mantler's projects. Mason's drumming seems very straightforward--he does little more than keep time. Yet with changing meters and a very loose sense of time, the drums parts were not as simple as they might seem. Mason describes the session as "great fun and very challenging. He [Mantler] had scored a lot of it, and it was actually easier to learn to read the parts than learn the sometimes very complicated, ever-changing bar lengths. Mike produced this, and I tried to play what he wanted. I do remember Steve Swallow, the bassist, was incredibly kind and helpful towards me. He would happily rehearse for as long as I needed to get the part. Most of the others could read well enough to get the while thing down in a tenth of the time it took me." Quite a difference from his latter-day work with Pink Floyd, in which Mason was regularly replaced by a session drummer on songs with meters that didn't come to him easily (such as "Mother" or "Two Suns in the Sunset").

Though Mason had little drumming experience outside of Pink Floyd, Mantler never considered replacing him. "I just liked the way he played, and he was someone open to and interested in playing something other than rock."

On May 11, 1984, Mason made his only live performance appearance with Carla Bley, on West German Radio (Westdeutscher Rundfunk). The band was an variation of the Something There group, with Mantler, Bley, Mason, and Swallow being joined by guitarist Bill Frisell, as well as Something There arranger Michael Gibbs conducting the Westdeutscher Rundfunk Orchestra. They performed excerpts from the album, plus a new composition entitled "Twenty-Five" (Mantler had been in the habit of using numbers for titles on and off since the '60s, and in fact five of the six tracks on Something There were named "Seventeen" through "Twenty-One", though, interestingly, they were not sequenced in numerical order.)

Mason then went on to record film scores and the Profiles album with Rick Fenn in 1985 and 1986, and as David Gilmour quietly began working on the first Pink Floyd album following Roger Waters' departure, Mason got involved with that as well.

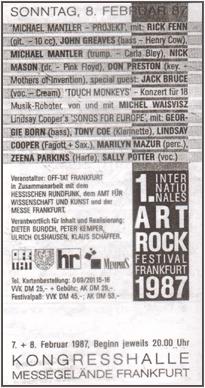

An advertisement for Michael Mantler's performance at the First International Art-Rock Festival in 1987.

|

In February 1987, Michael Mantler was invited to perform at the First International Art-Rock Festival in Frankfurt, Germany. The festival's producers suggested that Mantler be accompanied by an all-star band of sorts, and Mantler asked Mason to play drums Mason then introduced him to Rick Fenn, who was brought in as the guitarist. Rounding out the group was John Greaves (bass), Don Preston of the Mothers of Invention (synthesizer), and Jack Bruce of Cream (vocals). (Rick Fenn has since worked with Mantler on a number of recordings and the occasional live performance, as have Greaves, Preston, and Bruce.)

The concert included a number of compositions spanning Mantler's career, from 1973's No Answer and 1976's The Hapless Child right through Something There and Alien, a 1986 orchestral suite recorded by Mantler with Don Preston playing all of the orchestral parts on synthesizer. Mason remembers: "It seemed like a really fun exercise to work together and an honour to work with Jack. He was much easier than I expected. It was probably good practice [for the upcoming Floyd tour] as well. I do remember we were very loud." A portion of this concert was released in 1987 on a Michael Mantler live album.

Mason spent the better part of the next two years touring with Pink Floyd, and has not recorded or performed with Mantler, Bley, or the rest of the Fictitious Sports crowd since. Yet he has maintained his friendship with Mantler over the years. Mantler is not fond of performing, preferring the composer/arranger role. As Mason puts it: "I particularly enjoy Mike's love/hate (mainly hate) relationship with the trumpet. His attitude to playing an instrument has been more peculiar than my own."

Gary Wallis has supplemented the Floyd's touring band since 1987.

|

The subsequent tour exposed just how much Nick's playing had been affected by events surrounding him. On tour, the Floyd were aided and abetted by numerous extra musicians--a trend they had begun in the early 1970s, and continue to this day. The most pertinent new addition to the band for our purposes is that of Gary Wallis, a well-known (and excellent) drummer and percussionist who has played on more records and with more bands than you've probably ever heard of, let alone heard.

In 1987, the Floyd played three dates at the Atlanta Omni, with a view towards releasing the recordings as the first 'official' Floyd live video and to capitalise on the enormous success of their return. Being only a matter of weeks into the band's two-year tour, Nick was, by all accounts, still regaining his confidence and ability, with Gary playing most of the drum parts on his kit. Nick's playing--as also seen on Delicate Sound of Thunder video and the Live In Venice television broadcast--was noticeably less proficient than it once was. Being out of practice, the band quietly expanded their lineup to 'double up' each original member, but nowhere was this more visible than on the drums: flailing arms are always more noticeable than hands sliding over a keyboard or a fretboard. Nick performed the basic rhythm sans frills, leaving his trademark fills and thrills to Gary. From the distance of an American enormodrome, or duplicated on a concert CD, this would make no difference. To the viewer, though, the sight of Gary playing all of Nick's parts whilst Nick produced the skeletal outline was judged to be too much.

The Atlanta video (and planned subsequent live album) was quietly cancelled. Clips appeared on television shows and then on a bootleg DVD featuring some ten or so songs from the performance. The rest remains unseen on a shelf somewhere.

Gary Wallis (left) and Nick Mason are seen side-by-side in the crew photo from the Momentary Lapse tourbook.

|

As the tour progressed (and thus, as the setlist expanded to take into account the increasing confidence of the entire band), Nick's playing improved noticeably. He was playing more of the parts, and more often. Gary's role moved from the forefront of the band's sound to that of a side role, and while he still played a lot of the more complicated parts (especially for the Momentary Lapse of Reason material that Nick didn't really play on, full of tricky fills that overlaid the basic drum track), Nick was returning to the form which we know and love. By the time the band filmed their official record of that tour in 1988, Nick was performing as well as ever. Nothing can match the sight of seeing him play the toms on "Time" (apart from going back in time to 1974).

By the time the band returned in 1994 with The Division Bell there was no question that Nick had returned to his former glory. The album itself was recorded 'live' by the band at their studios in London with hardly an additional percussionist in sight. Gary still toured with the band live to augment Nick's playing--no matter how good a drummer you are, you need more than two arms to play some of the parts--but this time around, there were no aborted recordings and no momentary lapses of ability. Nick was unquestionably more confident and practiced, and coming back to life.

Sadly, as alluded to in Inside Out and numerous interviews, this may very well have been the last we ever see of Pink Floyd. Like many of the world's greatest drummers, Mason's style serves the song and not the ego. There are (thankfully) mercifully few drum solos in the Floyd oeuvre outside of the Sixties, and Mason's drumming always serves the needs of what makes a great song, and not a way of shoehorning in a particularly good bit of playing (unlike certain people we could mention). Like many of the best rhythm sections, a great drummer serves to complement the rest of the song, and is often--undeservedly--barely noticed.

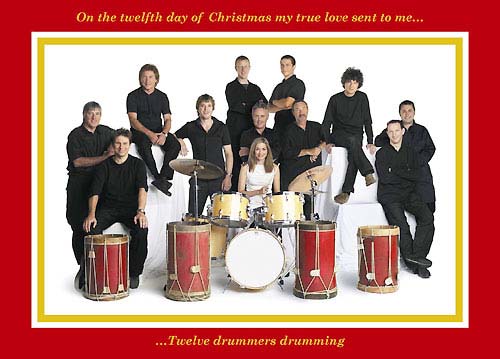

From the NSPCC's 2002 Twelve Days of Christmas campaign. From left to right: Mick Avory (Kinks), Roger Taylor (Duran Duran), Kenny Jones (Small Faces, The Who), Rob Green (Toploader), Dave Rowntree (Blur), Roger Taylor (Queen), Caroline Corr (The Corrs), Dylan Jones (Earth Sauce), Nick Mason (Pink Floyd), Eds Chester (The Bluetones), Darrin Mooney (Primal Scream), and Jon Brookes (Charlatans).

|

I observed that it was good that someone like Nick, who was already involved with the NSPCC, helped co-ordinate this, rather than purely having a celebrity name for an isolated occasion. I then asked him to tell me more about the Full Stop Campaign and how he came to notice that at first. "There's something very rewarding about working on a project, rather than just appearing for a one-off event. I think I was probably trying to be too clever at a dinner somewhere and someone who was already involved in the campaign said 'Oh that's a good idea' and I said 'Oh gosh, thanks very much' and next thing I knew I was on some committee, working on it, and I haven't been able to get off now for two years (laughs). Once you get involved you tend to learn more about what they're doing and what they're trying to achieve, and I've been to a couple of projects that the NSPCC are involved in and it's just such a worthy cause--worthy sounds a terrible word, doesn't it?--but I think anyone, particularly anyone with kids... it's an important cause, that's what it is.

"What the NSPCC are trying to do is raise a vast amount of money, which is £250,000,000 because they think with that sort of money and that sort of funding, they could really go along way to actually stamping out child abuse."

All the photos in the set were taken by Lord Litchfield. "He's just great to work with. He's so fast; I mean if he takes more than three shots, I think he feels he's let everyone down! He was really well prepared. When you're assembling twelve drummers, you might think that might be a rather tricky thing to do, but he knew exactly where everyone should be and put them in the right place and it just went so smoothly."

Into the Red: 21 Cars That Shaped a Century of Motorsport by Nick Mason and Mark Hales.

|

At the time I spoke to Nick, his book Into the Red had just been reprinted. "Ah, yes, it's one of those books that I don't feel anyone should be without!" ...a vintage car enthusiast's dream journal... "What I'd particularly recommend about this is the fact that with every book, inside the front cover is a CD of all those car sounds for those very, very sad people (laughs) who've stopped listening to music! Since [the original publication of the book] I've heard stories, which sound terrific... people who actually have CD players in their cars and put on the sound of some racing car leaving the start line at the traffic lights and wind the windows down!" (laughs)

For the disc, Nick assembled a pantheon of great vehicles from 1901 onwards and ran them to the best of their ability. I suggested that, as he owns these things, this must've been slightly scary to run them up to full speed. "Well, absolutely, which is why I didn't drive all of them myself! It was really interesting... I mean, first of all it's always nice to get the cars going--and going properly. The main reason for doing that was to try and make some comparisons, because what you very quickly learn is that people have been building very fast cars since, really, the dawn of motoring and it's actually things like brakes and suspension that have got a lot better. There's a lot of cars built in 1930 that can give fairly modern racing cars a run for their money in terms of straight-line speed."

After this, I took up the subject of Pink Floyd's first album. Nick said he didn't have a lot of time that day, but he could do ten minutes then and I could call him again for more. After about half an hour, he said he really needed to be somewhere else by 3pm--and it was already 2:55! After that, I had a few further points to clarify, which we did by e-mail while he was abroad. I found Nick Mason to be most helpful, very warm and I'd say he is a fine champion for the NSPCC... but I won't say "worthy", as I don't care for that word either and I think he's much more than that!

Gary Windo

|

Windo made quite a splash on the London music scene, playing jazz with the likes of Chick Corea and playing rock and R&B with names like Arthur Brown, Jack Bruce, and Graham Bond. (Ever the jokester, Windo often played up his American musical resume by presenting himself as an American expatriate, complete with a phony American accent.) He played with experimental jazz orchestras like Brotherhood of Breath and Centipede, where he met Robert Wyatt. Wyatt and Windo (along with Centipede bandmates Nick Evans, Mongezi Feza, and Roy Babbington) formed a band called Symbiosis in 1970.

It was by way of Wyatt that Windo eventually met Nick Mason. Wyatt and Mason had known each other since the heady days of the London Underground, when Mason's Pink Floyd and Wyatt's Soft Machine would often share billing--and fans. Mason produced Wyatt's Rock Bottom album in early 1974, and Gary Windo played saxophone on a few tracks. (Likewise, Mason produced Wyatt's 1975 Ruth is Stranger Than Richard, on which Windo also appeared.) Mason and Windo both shared the stage with Wyatt on September 8, 1974 at Theatre Royal on London's Drury Lane in Wyatt's 'comeback' concert a year after the accident that broke his spine and left him crippled.

Mason and Windo soon discovered that they had plenty in common. "When I met Gary," Nick recalls, "I think we discovered we were neighbours. He and his wife Pam became friends over the ensuing months." Pam Windo remembers: "Gary's father had been a RAF pilot in WWII and went into engineering after the war. Because of this, Gary had a lifelong love of planes and all mechanical things. He spent hours fixing our old VW camper, and then our Citroen 2CV. When he saw Nick's cars that were kept in a garage a few minutes from where we lived, he asked Nick if he could help work on them."

"There was not a lot of work for jazz sax players," says Mason. "Gary worked part time at Morntane Engineering as a general 'go-fer' and was great company. He never was actually entrusted with the re-builds, but he was also useful for the odd other-end of the spanner and did some delivery driving. It worked well because he knew that I understood that any music work would take precedence. He did suffer a bit at the hands of the regular mechanics."

Pam Windo says: "We had become fast friends; especially as Nick's house was only a few minutes from ours. Nick and his then-wife Lindy would come to dinner, sitting around on the floor with us, without raising an eyebrow. Our kids had sleepovers, and Gary saw Nick on a daily basis at the garage. We often went to race meets with Nick, Lindy, and their two girls Holly and Chloe. They were just a few years younger than Simon and Jamie, and got on really well."

But a love of the automotive was not the only thing that drew Mason and Windo together. As Pam Windo recalls, "the relationship grew slowly--and I think it was based on their mutual sense of humor. Nick always had a smile on his face, and always saw the funny side of things. Gary's zaniness made Nick laugh a lot."

"Gary was a really nice guy," Mason says, "and I liked Pam and the boys enormously as well. We both shared a similar sense of humour, although Gary was without doubt a lot more volatile than me. Perhaps with good reason. I had led a very sheltered existence in comparison. He was also an enormously accomplished player... any take was instantly usable. Gary probably respected my ability to achieve success with minimal talent, and believed I had organisational skills."

Pam remembers that Gary had been impressed by Dark Side of the Moon, and that "Gary saw the musician as a whole, not just for technique. On his albums, he only used musicians who he appreciated. We first met Nick as the producer for Rock Bottom, and it was Nick's ability to get the best out of everyone, and to be thoroughly involved in the production, that stuck with Gary."

Throughout the '70s, Windo played on a wide variety of musicians' recordings and concerts, including Hugh Hopper, Suzie Quatro, Joan Armatrading, and Gary Glitter, and worked as a sideman and bandleader for a variety of R&B and jazz-rock groups. Names like the Gary Windo Trio, the Gary Windo Quartet, the Gary Windo Orchestra, the Gary Windo Band, and the Gary Windo All-Stars rightly suggest the kind of loose-knit musical combos that performed regularly in various settings, but were seldom recorded.

One such outing took place in November 1975, when "Gary Windo & Friends" were booked for a gig at the Maidstone College of Art in Kent. Windo recruited Mason to play drums, and brought in guitarist Richard Brunton (who had been in a band called 'I Dogou' with Windo and Mongezi Feza in 1974) and Matching Mole bassist Bill MacCormick to fill out the band. This show also marked the debut appearance of Pam Windo on piano. "It was just another in Gary's endless spontaneous collaborations," she recalls. "I had composed a couple of things that Gary liked, so he simply put me in the group!"

This was 1975, and Pink Floyd was at the top of the pop music world, with the group's two most-recent records being monster hits. As the story goes, Mason didn't want his involvement to draw attention from what was supposed to be Gary's gig, and the promoter agreed not to publicize Mason's appearance. Nevertheless, the word got out (quite possibly the same promoter's doing), and Floyd fans packed the hall. Pam Windo remembers "Nick would probably have preferred it hadn't leaked out; he wanted to be low-key and blend in with the rest of us unknowns! But he didn't get angry--I never saw him angry ever--he just enjoyed the concert. I remember at a pub after a brief soundcheck he raised his beer glass to me and said with a grin, 'Here's to your debut, dear!'"

Mason remembers the show as "great fun, though I think a friend of a friend must have booked Gary since that sort of music was not really student union fare." Pam Windo recalls that the music "was received well, although personally speaking I was obviously very nervous, which wasn't helped by having to play an out-of-tune, barely-audible piano and not being able to hear myself sing."

With such a firm friendship between them, it seems perfectly natural that Windo would ask Mason to produce his Steam Radio Tapes album. "Brit Row had just been completed," Mason recalls, "and we were able to do the recordings as test sessions to check out all the systems. I think Nick Griffiths did some of the engineering, and I did a certain amount myself."

Recording began as early as April 1976, and occurred sporadically over the next two years. "Nick would call Gary in when he had time," Pam Windo recalls. "It was a very relaxed and fun atmosphere, and as all the musicians were friends of ours, including Lindy Mason who Gary insisted play flute on one track, there was always a very 'family' feel. Nick would stop and order in food, seeming to enjoy having all the musicians in his charge.... Nick had a ball; the sessions were often long and he was very keen on getting the best takes."

While much of Gary Windo's music is characterized by wild improvisation and raucous energy, several of the Steam Radio tracks have a more refined quality to them, a certain 'smoothness'. According to Pam Windo, "Nick enjoyed the wildness, but had to face the rawness and imperfections of Gary's tracks. He said it was a challenge, as the Floyd were 'slaves to perfection'. I always felt Nick loved producing these diametrically-opposed albums; it was as if he were 'on vacation' and didn't have to take himself so seriously. I think he always yearned to be improvising more."

"I think we all thought it would be good to try and make a more polished record than the usual jam session feel that a lot of jazz-based records used to have," Mason says. "There was little point in using me and a state-of-the-art studio and trying to make a 'live' or 'home-sounding' recording. It would be nice to think I did make it sound a little more polished."

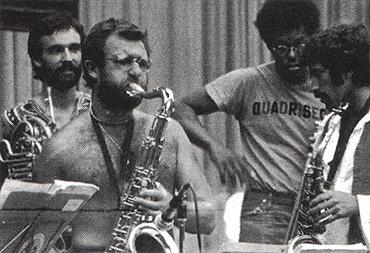

Gary Windo takes a solo with the Carla Bley Band, July 1978. (left to right: John Clark, Windo, Bob Stewart, Alan Braufman)

|

As was his wont, Gary Windo brought in a variety of musicians for the project. Some tracks featured the band from the Maidstone College of Art show: Richard Brunton, Bill MacCormick, Pam Windo, and Nick Mason. Hugh Hopper and Robert Wyatt made appearances, as did Steve Hillage and Laurie Allan from Gong. Drummer Peter Van Hooke and pianists Gary Mobeley and Mike Hugg of Manfred Mann also participated. Carla Bley played organ on one track during a brief visit to Brit Row.

Pam Windo recalls that during this period, Britannia Row became a home away from home. "It was very impressive, very organized; an office upstairs, with all kinds of musicians and management coming and going. We would often bump into Rick, Dave, and Roger there. Brit Row always had other projects being recorded there, which they fitted in between their own sessions." As the recording dates went on and on, Mason was not always involved; at least one recording session took place while Mason was on tour with Pink Floyd in 1977. "Probably one of the Floyd engineers covered for him," Pam says. "Nick Griffiths, or Brian Humphries, for example. About that time, Nick let me use Brit Row to record some of my songs, and Brian engineered them."

In a 1995 interview, Bill MacCormick said, "In April 1976 I played on the sessions for his Steam Radio Tapes. It started at his flat in Hampstead, quite a lot of it was working on songs that Pam his wife had written. We actually put a band together which played one gig, at Maidstone College of Art.... From that it evolved into the Steam Radio Tapes down at Britannia Row. Myself and Hugh Hopper played bass, often both of us on the same number, it's virtually impossible to tell who is playing what."

Gary Windo's Steam Radio Tapes |

Watch Out for the Bones |

The Steam Radio tracks ranged from quiet instrumentals and jazz-flavored funk written by Gary Windo, a couple of art-rock tunes penned by Pam Windo, and energetic R&B covers. Mason recalls: "We agreed on what to record and discussed the arrangements, but I have no sense of who had 'control' at any stage."

One aspect of the project--the title--was definitely Windo's. "The title was Gary's idea from the beginning," Pam Windo recalls. "I think it's possible Gary was alluding to his more old-fashioned way of recording versus that of Pink Floyd's ultra-modern technique." Mason concurs: "'Steam Radio' is a faintly common expression, used generally as an affectionate term [for radio] in comparison with television. Gary named it Steam Radio Tapes--old-fashioned [recordings] in a super-modern studio."

But slick production and all-star personnel aren't enough to make a record a hit. In the case of the Steam Radio Tapes, it wasn't even enough to rouse a record company's interest. As Mason remembers, "I think I gave [the tapes] to Gary at the end because I couldn't really do any more. [He] probably never managed to get a deal. Record companies haven't changed that much: there were no lyrics, and none of the band looked like Marc Bolan."

Gary Windo - Deep Water (1988)

|

With no label to release the album, the project was eventually abandoned and the recordings all but forgotten. One track--a short, multi-tracked, bass clarinet instrumental called "Ginkie" (after Gary's beloved grandfather)--was released on Windo's Deep Water album. But the rest of the Steam Radio recordings seemed lost forever until 1991, when Gary and producer/music historian Michael King started work on a retrospective album called His Master's Bones.

Three Steam Radio tracks were included on His Master's Bones. The first is "Watch Out for the Bones", an uptempo jazz-rock number anchored by Hugh Hopper's bass groove and outstanding solos by Steve Hillage, Hopper, and Windo himself. Next is Pam Windo's ballad "Letting Go", featuring the band that performed at Maidstone College of Art and a stunning vocal by Julie Tippetts, who had been part of Centipede, and had performed with Windo and Mason as part of Wyatt's 1974 comeback concert. The third track included is Pam's "Is This the Time?", an art-rock number with a plaintive vocal by Robert Wyatt, the duelling basses of Bill MacCormick and Hugh Hopper, and Nick Mason on drums. (This track was also released under the title "Now is the Time" on Robert Wyatt's 1994 retrospective album Flotsam Jetsam, also compiled by Michael King.)

Gary Windo - His Master's Bones (1996)

|

Also included is a version of Windo's composition "Standfast", recorded in November 1976 at the Baden-Baden Free Jazz Meeting in Germany, an annual event in which musicians are invited to develop new music. A different version of "Standfast" was recorded for the Steam Radio project as well, though a very different arrangement had also been recorded by Symbiosis in 1971 for the BBC's "Top Gear". There's no telling which of these the Steam Radio Tapes version resembled. But the Baden-Baden version is notable because in addition to Windo, 1976 participants included Carla Bley and Michael Mantler, as well as Hugh Hopper. This was likely the first meeting between Bley and Windo, and in 1977 Windo, Hopper, and Soft Machine saxophonist Elton Dean all temporarily joined Bley's big band.

In 2003, Pam Windo and Michael King assembled another retrospective of Gary's music entitled Anglo American, and two more Steam Radio were included. One was a variation of "Ginkie", though retitled "Round Ginkie". It appears to be the same recording as the one released on Deep Water, but sped up slightly, and overlaid with Windo's voice telling a tongue-in-cheek anecdote about having to beat up the other members of a band in order to get a solo.

Gary Windo - Anglo American (2004).

|

A brief R&B version of the traditional folk song "Red River Valley" (listed as 'still missing' in the liner notes for His Master's Bones) is also included on Anglo American, as is a 1979 re-working of "Is This the Time?", with Pam Windo on vocals (recorded for yet another unreleased Gary Windo project called Loaded Vinyl). The original Symbiosis version of "Standfast" is also found on this album.

After Steam Radio, Gary Windo and Nick Mason remained friends, though their musical paths seldom crossed. Windo returned to the U.S. to tour with the Carla Bley Band, and in 1979 he and Pam moved into a log cabin in upstate New York, very near Carla Bley and Michael Mantler's home and studio. Later that year, Nick and Gary met again during the recording of Mason's Fictitious Sports at Bley's studio. Windo left the Bley band in 1980, but stayed in the States, recording and performing on a freelance basis. He did film soundtracks, scored incidental music for Saturday Night Live, played on TV and radio commercials, and toured constantly with NRBQ, the Psychedelic Furs, and others. Gary and Pam divorced in 1984, but remained close friends until Gary's death.

In July 1992, at the age of 50, during a west coast tour with NRBQ, Windo developed pneumonia, and later suffered a cardiac arrest. Bill MacCormick said, "He was the wild man of the sax, a great player, lots of enthusiasm. When I heard he'd died it was a great shock, he seemed to have so much life left in him."