Features 2

The Light Kings of England

In search of the fabled Fifth Floyd

From 1966 through 1967, the Pink Floyd rose from a group of unknowns on the verge of a break-up to become the darlings of the London Underground scene. They did so almost entirely on the strength of their performances at legendary venues such as UFO and the Roundhouse, and concert events such as "Games for May" and "The 14-Hour Technicolour Dream".

Reading contemporary reviews of the shows, one fact becomes clear: the band's visuals garnered as much attention as the music. International Times, an underground newspaper, wrote of an October 1966 show, "The Pink Floyd psychedelic pop group did weird things to the feel of the event with their scary feed-back sounds, slide projections playing on their skin--drops of paint run riot on the slides to produce outer space/prehistoric textures on the skin--spotlights flashing on them in time with a drum beat." A review from November 1966 in The [Kent] Herald stated, "Without [the] psychological visual effects, the act would not be the same." In January 1967, Melody Maker's Nick Jones wrote, "The Pink Floyd have a promising sound, and some very groovy picture slides which attract far more attention than the group." The Floyd's light show became so famous that Tower Records promoted their brief 1967 American tour by calling them "The Light Kings of England".

The Floyds themselves are generally quick to point out that, musically, a lot of what they were doing at the time was quite amateurish. "It's funny when you're improvising and you're not particularly technically able," Nick Mason remembered. "It's once thing if you're Charlie Parker, it's another thing if you're us. The ratio of good stuff to bad stuff is not that great.... There was a hell of a lot of rubbish being played to get a few good ideas out."

In 1967 Mason said, "We don't call ourselves a psychedelic group or say that we play psychedelic pop music. It's just that people associate us with this and we get employed all the time at the various freak-outs and happenings in London." And Waters continued, "I think the reason is that we've been employed by so many of these freak-out merchants, I sometimes think that it's only because we have lots of equipment and lighting, and it saves the promoters from having to hire lighting for the group."

All that equipment and lighting was a popular part of the London Underground (and, as we'll soon see, lighting spectacles were among the first regular events that helped the Underground movement--and The Pink Floyd--gel in a meaningful way). Promoters sometimes advertised concert events based on the lighting (and other visual elements) as much as the musical acts.

(For example, in December 1967 the Kensington Post ran an article about the upcoming "Christmas On Earth Continued" concert. Rather than discuss the artist line-up that included Jimi Hendrix, The Who, The Soft Machine, The Pink Floyd, and many others, the article goes on and on about the light show. "In all more than a hundred projectors are being used throughout the building to make up a spectacular display of various lighting effects.... Two 30-feet high light towers with three projections levels incorporating a dozen radio-controlled follow spots are the center feature of the spectacular light show.")

The Floyd worked hard to make their lighting as impressive and inventive as possible. "With us," Waters said, "lights were not, and are not, a gimmick. We believe that a good light show enhances the music." Barrett remarked, "We think that the music and the lights are part of the same scene; one enhances and adds to the other." And Mason said, "We were very disorganised then until our managers materialised and we started looking for a guy to do the lights full time. The lighting man literally has to be one of the group."

It is this kind of statement that has led many Floyd contemporaries (and some Floyd historians) to the conclusion that the Floyd's various lighting technicians were, in fact, full-fledged members of the group. A November 23, 1966 article in the Kent Herald states that the group consisted of five people, with the light man, 17-year-old Joe Gannon, being the fifth member. (Rumors have circulated that Gannon was even included in the original six-way Blackhill Enterprises partnership, though this has been refuted by the Floyds themselves. The very nature of the Blackhill organization belies this story as well: Andrew King plus Peter Jenner plus Barrett, Mason, Waters, and Wright leaves no room for anyone else in a 'six-way' partnership.)

As a succession of others took charge of the Floyd's light shows over the ensuing months, they too were variously elevated to the status of 'fifth Floyd' in many a fan's mind. So who were these legendary men (and women) who created the Floyd's famous light shows?

("Legendary" is perhaps the most fitting word to describe this earliest period of the Pink Floyd's history, because the facts are so heavily shrouded in tall tales and hazy, drug-stained memories. Most of the 'authoritative' sources and books on the subject are incomplete, giving histories that are convoluted and often contradictory. Piecing together the precise sequence of events some 40 years later is virtually impossible--and largely frustrating. I'll try to straighten things out as best I can, in a chronological fashion, without introducing too many new half-truths and outright errors.)

Perhaps the earliest candidate for the title of Fifth Floyd was Mike Leonard, a lecturer at the Hornsey College of Arts and Crafts (a.k.a. Hornsey Art College). He was older than the future Floyds by some fifteen years, but was interested in pop music. Mason, Waters, and Wright were living in Leonard's house in London's Highgate neighborhood in 1964, and Leonard allowed their band, The Abdabs, to rehearse there.

Mike Leonard, with one of his experimental projectors, as seen in documentary footage from the 1960s. |

In 1964, Syd Barrett had moved to London to attend Camberwell Art College and had formed a band called The Spectrum Five, which included Mason, Waters, Wright, and Bob Klose. At some point that year Mason and Wright moved out of Leonard's house, and Barrett and Klose moved in. (This was, perhaps, around the time that Wright was expelled from Regent Street Polytechnic School of Architecture, and spent some time at the London College of Music, as well as on an extended holiday in Greece.)

With Wright gone, The Spectrum Five were forced to change their name (although I suppose 'The Spectrum Four' could have worked just as well). In honor of their landlord, they called themselves Leonard's Lodgers, and continued to rehearse in Leonard's living room. Eventually, they persuaded a few pub owners to let them perform, and Leonard even played keyboards with them at a few early shows.

"Leonard thought he was one of us, but in fact he wasn't at all," explained Mason. "He was too old, that's all. We even ended up going to our gigs in secret, without telling him." Despite being removed from onstage duties, Leonard continued to take interest in the band, even serving as a roadie for their few paying gigs.

But the most important contribution Leonard made to the fledgling Floyds was in the area of lighting. Like many of the Hornsey Art College faculty, Leonard was experimenting with combining light projection with music. (By one account, Hornsey students had been known to protest because the lecturers spent too much time fiddling around with lighting installations and not enough time actually teaching them.)

Through their connection with Leonard, the band was able to rehearse at Hornsey. There they became interested in some of the projections Leonard was doing. He would cut shapes out of pieces of colored cellophane, attach it to a rotating drum, and project light through it to create moving blobs of color. "He had projectors and things," said Waters, "and he would wrap up tubes of shiny Smelinex and shine light through it, and crinkle it, and see what it did when it hit the wall. And we would play music to it."

Documentary footage shows a cameraman filming Leonard's projection experiments at left, while the Floyd improvises a musical accompaniment. |

At some point in early 1965 Rick Wright returned to the group, and that summer Bob Klose left. And after a few more abortive name changes, the band finally settled on The Pink Floyd Sound. Barrett moved out of Leonard's house and moved in with Peter Wynne Wilson (a lighting technician at the New Theater) and Wilson's girlfriend Susie Gawler-Wright.

The band was moving toward proper performances as a pop band with appearances at the Marquee Club's "Giant Mystery Happening" and "Spontaneous Underground" in early 1966, but continued to play with Mike Leonard's projection experiments on the side. In March, they had an experience that foreshadowed a lot of what they would do visually in years to come.

"In 1966 we did a gig at Essex University," said Waters, in 1972. "We'd already become interested in mixed media, as it were, and some bright spark down there had done a film with a paraplegic in London, given this paraplegic a film camera and wheeled him round London filming his view. Now they showed it up on screen as we played."

March 1966 also saw the founding of the London Free School, a kind of underground Citizen's Advice Bureau and loose-knit quasi-university started by London School of Economics lecturer Peter Jenner and freelance photographer John "Hoppy" Hopkins. An eclectic group of students, activists, poets, musicians, and would-be hippies, they met informally in the basement of 26 Powis Terrace, in Notting Hill.

Peter Jenner turned up at one of the Marquee's "Spontaneous Underground" events in early 1966, and there first witnessed The Pink Floyd Sound. Some sources--such as Watkinson and Anderson's Crazy Diamond--claim he was at the Floyd's first Spontaneous Underground appearance on February 27, while others--such as Vernon Fitch's Pink Floyd Encyclopedia--place the meeting on the March 27 show. Floyd biographer Nicholas Schaffner claims it was May, though no such performance seems to have taken place. I suspect that Jenner, a leading figure on the blossoming underground scene, would have seen the Floyd early on at the Marquee, and then 'met' the band later--perhaps in May as Schaffner suggests.

At any rate, Jenner was interested in signing a pop group to his DNA record label, and approached the band at Mike Leonard's Highgate house. Unfortunately for him, the band was about to leave for summer vacation (as Mason and Waters were still enrolled at Regent Street Polytechnic). And, to make things worse, they were thinking of breaking up and quitting the music 'business' altogether, having become discouraged by their difficulty in booking gigs, their student commitments, and Barrett's continued interest in painting.

But for one reason or another, the group decided to muddle on, and continued to experiment with lighting as an integral part of their performances. Underground: The London Alternative Press 1966-1974 describes underground luminary Barry Miles' seeing a band called the Abdabs at a place called the Goings On Club that summer. The Abdabs, so the story goes, "specialised in serious experimentation in sound and light, wore white coats, and would discuss their work, post-performance, with the equally serious audience."

(And yet this seems to be yet another wildly inaccurate story, lying somewhere between complete fabrication and foggy memory. The 'Abdabs' name had been abandoned at least two years earlier, and the group--which pre-dated Barrett's involvement--had never performed anywhere, except as extras in an unidentified film. I wonder if Miles' description is of a performance by the highly experimental AMM, who were known for wearing white lab coats.)

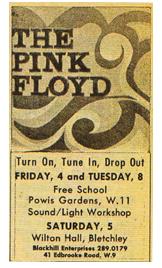

Eventually, Jenner's London Free School began publishing a community newsletter, and needed to raise funds to support it. The vicar of the nearby All Saints' Church (in Powis Square--not Powis Gardens, as advertised) allowed community groups to use the church's meeting hall for events, so it was here the London Free School hosted a concert 'happening' called the Sound and Light Workshop. The first such event was on September 30, 1966, and featured a performance by The Pink Floyd. The mimeographed handbills also advertised the light projection slides and 'liquid movies'.

Though Hopkins admitted that the Workshops were "a way to recoup some debts and have a good time," they were also purportedly educational activities for the artistically-inclined. Miles recalled that after one such Workshop, the Floyd "took questions from the audience, while earnest young avant-gardists like myself asked about multimedia experiments and all the rest of it. It was an 'educational event,' very serious." (And this sounds similar to the purported 'Abdabs' concert described by Miles above--perhaps he just got two similarly experimental shows confused.)

The first Sound and Light Workshop was a success, and it subsequently became a regular Friday-night event, even as the London Free School faded away. The Marquee Club's "Spontaneous Underground" shows in early 1966 may have been the Floyd's first exposure to something approaching steady work, but it was at the All Saints Hall that the band really began to develop a serious following. The group had played there nearly a dozen times by the end of the year.

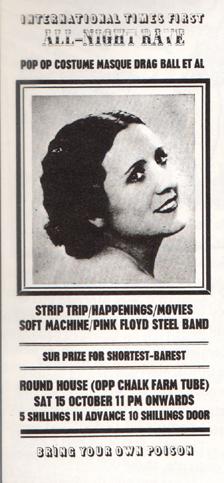

The IT All-Night Rave at the Roundhouse marked the first appearance of The Pink Floyd's custom lighting gear. |

And as usual, it was the band's light show that garnered the most praise. Melody Maker reviewed the second All Saints' Hall show (October 14) by saying "the slides were excellent--colourful, frightening, grotesque, beautiful", but the most they could say about the band's music was that it "promised very interesting things to come. Unfortunately all fell a bit flat in the cold reality of All Saints Hall...."

Another major development in the Floyd's light show took place at one of these early Sound and Light Workshops in either September or October, depending on the source. Joel and Toni Brown, Americans from Timothy Leary's Millbrook Institute, visited London and showed up at All Saints Hall one Friday evening with a projector and some non-moving 'psychedelic' slides, which they proceeded to project on the Floyd in time to the music. Some authors credit the Browns with being the first to project slides on the Floyd.

On October 15 the band played their first show at the Roundhouse at an All-Night Rave promoting the launch of an underground newspaper called International Times (or IT), launched by Barry Miles, John Hopkins, and others.

Peter Jenner, along with his partner/investor Andrew King, had started talking business with the band again, buying them a £1000 of equipment, and convincing them to drop the 'Sound' from their name. They also sought to augment the Floyd's usual oil slide projections, perhaps inspired by the effects created by the Browns. For the Roundhouse show, Jenner and King put together the Floyd's first custom lighting rig: common domestic light bulbs shining through pieces of colored plastic mounted on a crude wooden frame, all controlled by light switches purchased at a home-improvement store.

"On the original Pink Floyd lighting rig Andrew and myself had built," Jenner recalled, "because of the low-powered lights we set them up so they'd throw a huge shadow. It was all very unlike the stunning high-tech flash of the Fillmore. But, in a way, the Floyd's was more imaginative." Jenner admits that they were trying to reproduce what they imagined the Haight-Asbury psychedelic scene was like, without any of them having any actually experienced it.

The band had recruited Pip Carter, a friend from Cambridge, to man the light board. According to one source, at one point Carter went looking for a some wood to make repairs to the contraption, and he and Barrett tore off a piece of lumber that was supporting a giant gelatin ('jelly') mold that was supposed to be part of the evening's program.

This image from the Floyd's appearance on the BBC's Look of the Week (May 14, 1967) demonstrates both the liquid slide projection and the creative use of shadows that were part of the Floyd's lighting since 1966. |

(Again, we are faced with contradictory accounts. Crazy Diamond tells the story of Barrett and Carter accidentally demolishing the jelly--though the authors mistakenly list the date as October 11. The 'official' account published in IT said that the jelly was run over by a bicycle, while Miles later claimed that the Floyd knocked it over with their van while setting up. The jelly's size has been variously described as six feet and seventeen feet, and the Sunday Times reported that the event's attendees had actually eaten the jelly, suggesting that it wasn't ruined at all.)

At any rate, the first Roundhouse event was a logistical nightmare, but upwards of two thousand people were there, and it was the Floyd's first really big concert--for which they were paid a whopping £15.

Jenner and King were eager to formalize their investment in The Pink Floyd, and on October 31, 1966, they formed Blackhill Enterprises, a six-way partnership with the band. Jenner and King would take on managerial duties, which, along with their financial backing, would entitle them to equal shares of the band's earnings. Thus, they had every reason to encourage the Floyd's lighting experiments, as this was the most unique (and marketable) aspect of their act at the moment. Much of the band's meager profits were re-invested in more expensive lighting gear and more powerful amplifiers.

An newspaper clipping advertising the London Free School Sound and Light Workshops in November 1966. |

On November 5, the Floyd performed at the clubhouse of a park called Five Acres, which was managed by Jack Bracelin. Bracelin later operated a business called Five Acre Lights, which sometimes provided lighting effects for the Floyd at the All Saints' Hall workshops. The Floyd continued performing at All Saints Hall workshops through late November. Advertisements read "experimentalists welcome", thus attracting more and more like-minded lighting enthusiasts.

One such 'experimentalist' was 17-year-old Joe Gannon, who became the Floyd's de facto lighting technician and projectionist after Joel and Toni Brown returned to America. He worked extensively with the Floyd during this time, refining and redesigning their lightshow. "I design the slides, basing them on my idea of the music," Gannon told The Kent Herald in November 1966. "The lights work rhythmically. I just wave my have over the micro-switches and the different colors flash. We have only been using the lights for one month. But before that, we were concentrating on starting with the right equipment. The lighting is so much a part of the group that it had to be good before it could blend properly with the music."

In coming weeks, Gannon would also express interest in creating a direct link between the music and the visual effects, as well as in replacing the slides with moving film.

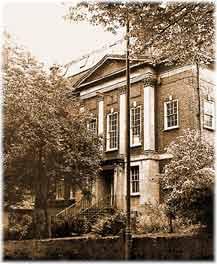

On November 18, the Floyd's fascination with creative lighting effects came full circle, as they played a show at Hornsey College of Art, where it all began (sort of). Like so many concerts at the time, this show was given a strange title: "Philadelic Music for Simian Hominids". But the real attraction was that the college's Advanced Studies Group (of which Gannon was a part) was presenting lighting effects with equipment they had designed and built as part of their course work, all set to the Floyd's music.

Hornsey Art College, as it was in the 1960s. In 1973 Hornsey merged with Enfield and Hendon Colleges to form Middlesex Polytechnic. The original building was demolished in the early 1980s. |

But for all their experimentation, the Floyd's light show didn't always impress. After the Floyd's final All Saints' Hall show, on November 29, International Times' Norman Evans wrote "Since I last saw the Pink Floyd they've got hold of bigger amplifiers, new light gear and a rave from Paul McCartney.... Visually the show was less adventurous. Three projectors bathed the group, the walls and sometimes the audience in vivid colour. But the colour was fairly static and there was no searching for the brain alpha rhythms by chopping the focus of the images. The equipment that the group is using now is infant electronics: let's see what they will do with the grownup electronics that a colour television industry will make available."

Gannon continued to experiment and refine his techniques, aided by a bookshop clerk named John Marsh, as well as Barrett's roommates Peter Wynne Wilson (who had also become the Floyd's infamous non-driving roadie) and Susie Gawler-Wright. Wilson built more custom lighting equipment, using gear discarded by West End theaters, as well as a lightboard that could be played like a keyboard to control the spotlights.

Wilson also helped create the liquid slides during performances. "Peter got into slapping Doctor Martin's inks on slides--very bright colors," Susie Gawler-Wright recalled. "We'd drop in different chemicals: it was very messy and very good fun. We'd get a blowtorch to heat it and a hair dryer to cool it. I used to watch the bubbles moving and thought it was really wonderful."

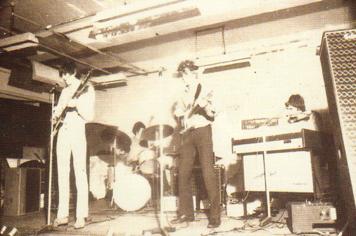

The Pink Floyd performs at Hornsey Art College, November 18, 1966. |

Joe Gannon would soon leave the Floyd and emigrate to America, though he continued to do a lot of lighting and other technical production work for a wide variety of musicians, from Alice Cooper and Frank Zappa to Neil Diamond and Barry Manilow. But his departure cleared the way for Peter Wynne Wilson to become the Floyd's lighting specialist. And subsequently, Wilson became one of the leading lightshow designers for London's premiere underground venue--UFO.

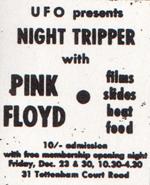

An ad for UFO's first two nights. |

If the Marquee Club was where the fledgling Floyd first got any serious exposure, and All Saints' Hall that they first developed a following, it was UFO that helped make them stars. From the very first "Night Tripper" event in December 1966, through September 1967, the Pink Floyd was such a fixture at the all-night underground 'club' known as UFO (which played host to artists such as Arthur Brown, The Soft Machine, The Move, and Eric Burdon and the Animals) that they were considered the 'house band'.

Just as the London Free School first started sponsoring the Sound and Light Workshops in order to fund its community newsletter, UFO was first started to help fund the International Times, which was losing money rapidly. It was the idea of Joe Boyd, a representative of Elektra Records and yet another prominent underground figure, to move the Light and Sound Workshop from All Saints' Hall to a larger downtown space to accommodate the crowds. Boyd and John Hopkins rented a dance hall on Tottenham Court Road called the Blarney for two successive Fridays. "If it works, it works; if it doesn't, its just two gigs," Hopkins told Nicholas Schaffner years later.

The first night, December 23, 1966, was billed as "UFO presents Night Tripper". (Boyd preferred the "UFO" name, while Hopkins preferred "Night Tripper", and ultimately Boyd won out.) In addition to bands, poets, and experimental performance artists, several different lighting designers were given space to create lighting displays. Peter Wynne Wilson and Russell Page did one area, while Five Acres' Jack Bracelin did another, and Mark Boyle did still another.

The Pink Floyd performs at the opening night of UFO, December 23, 1966. |

Wilson called UFO a "responsive situation", where the band could develop its music and he could develop the lighting, both working together. He developed "a group of four lights for each member of the band. I made a thing that went round the corner of Rick's organ to get his head and shoulders. There was one in front of the drums, one each in front of Syd and Roger. Apart from illuminating them they would cast shadows up on the screen behind. Where you've got a shadow of one spot, if you've got another playing on the screen, then you'd get a colored shadow. So you'd get these colored shadows of the band dancing on the screen--that was always great, especially because you had instant control of it, so you could react to the music very nicely."

Some sources credit Mark Boyle as being UFO's standard, in-house lighting guru, while others give this title to Wilson. Both may have been instrumental in creating the club's atmosphere, but it was Boyle who managed to market his lighting as Art, and then spin it into a career. Wilson may have been connected with UFO in people's minds due to his role as the Floyd's main lighting designer at the time. Since the Floyd became synonymous with UFO, perhaps so did Wilson. It certainly seems that the popular notion that the Floyd's lighting man was so integral to the Floyd's show that he was a member of the group came about during this period.

Whatever the case, the first two UFO events (December 23 and 30) were successful enough to warrant continuing into the next month. The Floyd appeared there on four consecutive Fridays in January--thus cementing their reputation as UFO's 'house band'--before settling into a routine of playing there once a month or so until the club folded in the autumn.

When German television program Die Jungen Nachwandler filmed the Floyd at UFO (presumably on January 20, 1967), they showed a few brief glimpses of this lighting technician (possibly Peter Wynne Wilson) at work. |

January 1967 also brought Chet Helms (who ran the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco) to London for a visit, hoping to try to start up a club in London. Miles and Hopkins showed him around, and though he quickly abandoned plans to start his own club, he was well received by London's underground. Helms, in turn, was impressed with the London scene. "UFO was pretty parallel to what was happening in the Haight, in the sense that your traditional rock 'n' roll was run by a pretty hoody kind of criminal element, while the young rebellious politicos such as Hoppy and myself were creating their own alternative venue.... At least from my outside perception, there seemed to be little distinction between UFO and Pink Floyd, and IT magazine for that matter. It was all the same circle of people who hung out together and smoked dope together."

While the Floyds saw the light shows as important to what they were doing, they were perhaps a little tired of so much attention being given to what was happening visually. In January, Mason told the Record Mirror, "The trouble with the projected slides is that everybody tends to ignore the music.... To us the sound is at least as important as the visual aspect."

But the music was really only beginning to come into its own. The fact is that many contemporary independent observers wrote that the music was loud and experimental, but it was the light shows that were most interesting, and which really set the Pink Floyd apart. As Helms put it, "The Pink Floyd were pretty much the house band, the way Big Brother and the Holding Company were for me. I remember feeling that our music was much more musical, probably because it had its roots in American R&B.... My experience of the Floyd was that it was amelodic and atonal.... What was unique about them was they worked invariably with the light show; they were the only act in England at that time where that was part of the act."

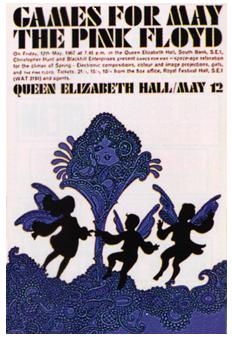

Games For May, May 12, 1967 |

Eventually, however, the band's music did take center stage, though visual experiments remained an important part of the group's act. At the famous "Games for May" event on May 12, 1967, Wilson projected an artificial sunrise on the screen and a liquid light show augmented by 35mm films. He also created thousands of cascading soap bubbles that filled the hall--and left soap rings on the leather seats. (The Floyd was subsequently banned from ever playing at the prestigious Queen Elizabeth Hall again).

The Financial Times (which, I'll admit, seems a strange publication to be reviewing a Pink Floyd concert) said this of the Games For May show: "Pink Floyd have successfully grafted vision onto sound in their performance by the skilful use of projected colours.... On a backcloth shapes like amoeba under a microscope ebbed and flowed with the glimpse of an occasional human form." But even after all this time, the lights still get better reviews. "Musically the Floyd are not outstanding.... In the more strident songs the words were completely lost, and the sound became just an accompaniment to the colours rather than a partnership."

But the Floyd's popularity and continued to grow with the release of singles and the Piper at the Gates of Dawn album. They toured Britain, Europe, and even (briefly) America. Upon returning to England, they embarked upon a 3-week British tour supporting The Jimi Hendrix Experience. Peter Wynne Wilson remembers a special lighting effect that he unveiled on the first night of the tour, November 14, 1967, at the Royal Albert Hall. "I would run the two units up to speed, then fade the lights in them, and you'd get a slightly shimmery white light. But as I then brought the speed down, any rapid movement would trail rainbows behind it. So the first thing you'd see was that Nick's hands would become a bit colored, given that he was moving faster than the others. And then as the speed came further down, the rainbows would broaden out--until the whole stage area was pulsing with color. But you couldn't actually figure out what color, because it was changing so fast. That was a wonderful effect. It could give all the entrancing qualities of strobe, but without that heavy jerking that sets people off into unpleasant situations. I very rarely used strobes on the Floyd because I always felt it was a bit violent for the music we were into."

Wilson apparently stopped working with Pink Floyd in December 1967, and his assistant John Marsh assumed the lighting duties. Although Wilson was at one time Barrett's roommate, and was very much one of his acid buddies and a fellow firm believer in the underground ideals, it is perhaps only coincidental that Wilson ended his association with the group at about the same time that Barrett did.

But Wilson takes a much more conspiratorial view. He had been earning a percentage of the band's nightly gross in addition of a weekly salary. With Blackhill always seeming to teeter on the brink of financial ruin, his five percent was highly coveted--especially since he often took home more than the musicians! Wilson claims that his removal from the lighting board was orchestrated by the band itself, with Marsh (who just happened to be King and Jenner's tenant) happy to step in.

Marsh had started out as a volunteer lighting assistant, and had lost his day job as a bookstore clerk for taking too many days off. He was put on the Blackhill payroll at a weekly salary lower than Wilson's had been, and without any percentage. Marsh stayed on as the Floyd's light man even after the band formally dissolved its association with Blackhill and moved on to the greener pastures of the Bryan Morrison Agency in April 1968.

Nearly 30 years later, the Floyd called upon Wilson to design the liquid slide effects used during performances of Barrett's "Astronomy Domine" during the 1994 tour.

So who deserves the title of being the 'fifth Floyd' lighting man? Mike Leonard, whose projection experiments was the group's first exposure to combining light and sound? Joel and Toni Brown, who first brought West Coast slide projection techniques to a Floyd performance? Peter Jenner and Andrew King, who funded and built the band's first lighting rig, or Pip Carter, who first operated it? Joe Gannon, who refined the rig, and apparently claimed the title for himself? Peter Wynne Wilson, who ran the lights and slides for most of 1967, including the band's reputation-making appearances at UFO?

In retrospect, it seems that most Floyd biographers tend to portray different people as being 'the main Floyd light man' based on who they are able to interview. Watkinson and Anderson seem to have interviewed Pip Carter, so his role is played up in Crazy Diamond. Nicholas Schaffner had extensive interviews with Wilson, so he plays up Wilson's role with the band. Others focus on Joe Gannon's early role. The truth seems to be that many people played instrumental roles in creating the Floyd's legendary light shows, and that each was, in his own way, indispensable.

Mason's remark that "The lighting man literally has to be one of the group" has been spun by many misguided authors to suggest that the band considered the lighting men to be full-fledged members of the group, but this does not seem to have been the case. The distinction Mason was probably making was that while many groups simply use the lighting at whatever venue they were playing, the Pink Floyd was unique in that they brought their own light show, operated by employees who knew the Floyd's music and how best to enhance it.

As Waters put it, "We take all the lighting equipment and get it set up before the show starts. Then our lighting manager takes over while we're playing and it's up to him to choose light sequences which strike him as being harmonious with the sounds being produced by us." He never claims that the light man was a member of the group--he doesn't even give him a name! Regardless of which nameless 'lighting manager' filled this role, the Floyds seem to have considered each of their lighting designers to be an important creative associate.

Pink Fraud How Roger Waters created a fair forgery of the Floyd sound "If one of us was going to be called Pink Floyd, it's me." -- Roger Waters Before I get started, remember this. Everything Roger Waters said about Pink Floyd (1987) Inc. could also be applied to Roger Waters. For every comment about frauds and forgeries, every last aside about talent and deception, Roger is just as guilty. The only difference is that Roger never called himself Pink Floyd. But if he could have, well, he would have. When Roger left Pink Floyd and began his solo career with The Pros And Cons Of Hitch Hiking in 1983, he did what he later lambasted his former bandmates for: he took the Floyd legacy, armed himself with all of his former accomplices that he could muster, and set off to be more Floyd than Floyd. Pink Fraud, if you like. As great rock divorces go, Roger Waters' exit from Pink Floyd is probably the messiest. It's also one of the most controversial amongst fans; there is an unspoken rule that you don't discuss whether you prefer Roger Waters and his surrogate band or the David Gilmour-fronted Pink Floyd. It's the unwinnable war. It never quite got to the point where there were two bands touring simultaneously under the same name--leave that to the faded stars of '80s disco--but it very nearly could have been. Instead, 1987 saw two bands, one called 'Pink Floyd', the other called 'Roger Waters', criss-crossing the US, both containing former members of Pink Floyd, both performing huge swaths of Pink Floyd songs. For all intents and purposes, both Roger Waters and David Gilmour tried their hardest to completely recreate Pink Floyd, its former former glory and bankability, by creating--as Roger Waters once put it--"a reasonably fair and accurate forgery" of their past using session men and hired hands. Poaching players, producers, alumni from each other's bands, mutual college friends, and visual artists to fake--or re-create--the Pink Floyd brand. Lost For Words There was plenty of mudslinging in the press, most notably the 1987 Rolling Stone and 1988 Penthouse interviews, which to this day probably stand as the apex of any public war of words. Make no mistakes: if Pink Floyd and Roger Waters were neighbouring countries, at least one of them would have built a wall or sent in Panzers by now. It's only rock 'n' roll, eh? Instead of taking sides, let's look at how Roger Waters' post-Floyd bands sought to recreate Pink Floyd as much as possible, without the messy business of dealing with David Gilmour, Nick Mason, or Rick Wright. Let's look at how Pink Floyd (1987) Limited and Roger Waters are, whether they like or not, merely two sides of the same coin--playing the same songs, often with some of the same people defecting between bitter warring factions. Towards the end of the 1970s, Pink Floyd had effectively become Roger's backing band. It is debatable whether this was due to the creative well's running dry in the rest of the group or Roger's being a demagogue. Each side has its own opinions. What can be certain is that when Roger started writing all the songs on the Pink Floyd albums, the other members starting making solo records. And "Signs of Life", the first song on the Floyd's first post-Waters album, was originally written in 1978, around the time Roger ceased writing with his bandmates. This surely is not be a coincidence. David: "He forced his way to become the central figure... that's what he really wanted, to be that central figure. I felt, and I'm sure Nick did too, that it was not the best thing to happen. As productive as we were, we could have been making better records if Roger had been willing to back off a little, to be more open to other people's input. It wasn't like we were all there leaning on him to look after us. It was a question of him having forced his way to that position, of him being very tough and having more energy for that sort of fighting." (Rolling Stone, 1987). They sent us along as a surrogate band Bringing in supplemental musicians was nothing new to the Floyd. Beginning in 1973, Pink Floyd (in whatever form they took) always augmented their lineup with a vast array of outside musicians. First they started with a trio of backing vocalists, including Clare Torry, who contributed the vocal solo to "The Great Gig in the Sky". We will hear a lot more from her later, flitting between Roger's solo band and the Floyd. In 1976, the first major player--and one who still tours with Roger Waters' Surrogate Band to this day--joined the Floyd. Taking on the mantle of guitar, and substituting for Roger on bass and guitar throughout the band's live shows for the next decade, came Snowy White. Over the years Snowy would be seen by many as the fifth Floyd. He contributed to the Animals sessions (though you can only hear him on the obscure 8-track version of "Pigs on the Wing"), played guitar and bass on the 1977 "In The Flesh" tour, and was an integral part of the Surrogate Band that performed at the Wall concerts of 1980. By the time of the Wall shows, even the concept of Pink Floyd was flexible: there was a full four-piece band that performed the first number without anyone from the band onstage. And longtime keyboardist Rick Wright had been ejected from the group, before returning on wages to bolster up the impression that this was a group--no different from his role during the 1987-1989 tour, then. "He wasn't performing in any way for us; he certainly wasn't doing the job he was paid to do. On The Wall... Rick didn't play many keyboards." - David Gilmour, 1984 When Roger Waters described them during "In The Flesh" as a surrogate band, he was only half wrong. Of the 11 people on stage, only three were actually in Pink Floyd. Of the 11 people on stage on the Momentary Lapse of Reason tour of 1987-89, only three of them were actually in Pink Floyd. So who is wrong, and who is right? The Final Cut "You could say that The Final Cut was essentially the first Roger Waters solo album". - Roger Waters, Uncut, 2004. Fast-forward through The Wall debacle to late 1982. Immediately after completing new recordings for the soundtrack of Wall film, what was nominally called 'Pink Floyd' were recording their death throes under the title of The Final Cut. Aided and abetted by a supporting cast of dozens, the three-piece Floyd stumbled on. By the end of the record though, it was all over. Nobody really knew what was in the future for the Floyd. What is certain is that, as time went on, the contributions of David Gilmour, Nick Mason, and Rick Wright diminished, to such an extent that by the closing notes of "Two Suns In The Sunset", Nick was no longer playing drums, Rick had been unceremoniously fired three years previous and replaced by Michael Kamen, and Gilmour--who sang half a song on the LP--had his producer's credit removed from the album sleeve. David: "Basically, he felt and says that I was being willfully obstructive...(visibly bristles)...which is absolutely not true. My criticisms and objections were constructive in the best possible way. They are the sort of constructive criticisms that made other albums, like The Wall." Roger: "There wasn't any room for anyone else to be writing. If there were chord sequences there, I would always use them. There was no point in Gilmour, Mason or Wright trying to write lyrics. Because they'll never be as good as mine. Gilmour's lyrics are very third-rate. They always will be. And in comparison with what I do, I'm sure he'd agree. He's just not as good. I didn't play the guitar solos; he didn't write any lyrics." Nick: "Dave found himself particularly picked on during The Final Cut. I found myself feeling that this was not fair." (Rolling Stone 1987) The Floyd were no strangers to having someone else in the drum stool though. "Mother", from The Wall, featured Jeff Porcaro on drums, as Nick wasn't able to play it precisely. And there is more than one additional drummer on A Momentary Lapse of Reason--one reason being that Mason's confidence in his drumming was at an all-time low after months of harsh words during the Final Cut sessions. The Final Cut was also the only Floyd album not to be accompanied by a tour. There was no band to take on tour. Rumours had it that Waters had openly stated he would never work with the remaining members of The Floyd again... and the feeling was mutual. Waters said so himself in a band meeting near the end when he announced to the rest of the band, "I'll never work with you guys again". In Waters' mind, the Floyd were defunct, so much so that he attempted to sue Gilmour and Mason in 1986, claiming that the Floyd were "creatively a spent force". So Roger began rebuilding his vision of what Pink Floyd was, but without having to deal with Gilmour, Mason, or Wright. And, three years later, the remaining Floyds were to do much the same thing in reverse. A Moment of Clarity A month after The Final Cut was finished, Roger Waters went back into the exact same studio--complete with everyone who had worked on The Final Cut except David Gilmour and Nick Mason--and recorded The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking. Roger kept Michael Kamen and took him on tour. He also recruited Eric Clapton, a guitarist who has often been heard to say that he saw Dave Gilmour (the man he was replacing) as a major influence. And David Gilmour said exactly the same in 1984. If you compare the credits of the two records, two people have left, and two have joined. David Gilmour and Nick Mason were not to be on this record. Eric Clapton had replaced David, and Gerald Scarfe--the visual artist who had characterised Pink Floyd's visual sensibilities on record covers, film, and tour since the 1975 shows--had rejoined the fold. Tim Renwick, a former Cambridge alumnus and pre-Floyd bandmate of Gilmour's, was also brought on-board, this time to mimic Gilmour. The Pros and Cons Of Hitch Hiking band then was the first of Waters' surrogate bands, made up of everybody from Pink Floyd but Pink Floyd themselves, both onstage and off. With a set made exclusively of Pink Floyd songs (if you count Pros and Cons as a Pink Floyd album, which it was originally planned to be). The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking The problem with The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking is simple: it's not very good. Which is exactly what Pink Floyd said to Roger in 1978 when he presented them with it as an idea for their next album. After listening to the demos, the rest of the Floyd diplomatically suggested that The Wall, Roger's other idea at the time, was more interesting. Exactly when a Waters-led Floyd was due to record Pros and Cons in an act of contract-filling desperation is unknown. But recording an album of songs originally rejected by the band, and releasing it under the Floyd name was nothing new: The Final Cut contained several songs originally dropped from The Wall. In the end, Waters decided that he didn't need the Pink Floyd anymore. The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking is merely the Pink Floyd album that Pink Floyd never made. So Waters cast the Floyd in his own image, and carried on anyway. For all practical purposes, Roger was assembling a new version of Pink Floyd. He took in longstanding Floyd collaborators such as Michael Kamen, Snowy White, Tim Renwick (a Cambridge friend of Gilmour's, who later joined the Floyd for their 1987-94 tour), and Andy Fairweather-Low, another Cambridge musician, for the Pros and Cons tour--a trio of musicians to replace Gilmour. Roger then set about touring the world in exactly the same fashion as Pink Floyd, barring the troublesome Gilmour and Mason. But as Roger was to learn, Pink Floyd was more than the sum of the parts. A Momentary Lapse of Reason In Roger's mind there was no more Pink Floyd. And when pressured by Steve O'Rourke, the Floyd manager, to consider recording with Gilmour and Mason again to fulfill the contractual obligations of the band, Roger fired O'Rourke. Unless he left, Waters may very well have had his royalties withheld because of breach of contract to provide new material. Roger: "They forced me to resign from the band, because if I didn't the resulting financial repercussions would have wiped me out completely". (Uncut, 2004) Waters then offered Gilmour a series of compromise deals in which he essentially would let them have the Pink Floyd name if they ratified his dismissal of O'Rourke. In doing so, Waters was taking a calculated risk that Gilmour and Mason would not continue as the Floyd. Roger: "Don't ask me why they never took that deal." (Rolling Stone 1987) During his final meetings with the band in 1985 and 1986, Waters made it clear that he was leaving, and that the Floyd name should be put to rest. In the end it came: a legal letter to the Floyd's record company in December 1985 declaring that Waters had left the group. In Roger's mind this would effectively be the dissolution Pink Floyd, and with a relatively successful solo tour and album, there was no reason not to think that Waters could become Pink Floyd in all but name, the name itself being in absentia. Roger: "I had decided that the band had run its course and as a creative unit. It was my belief, rightly or wrongly, I had thought we were finished." David: "We'd been having these meetings in which Roger said, 'I'm not working with you guys again.' He'd say to me, 'Are you going to carry on?' And I'd say, quite honestly, 'I don't know. But when we're good and ready, I'll tell everyone what the plan is. And we'll get on with it.' I think partly his letter was to gear us up into doing something. Nick: "Because he believed very strongly that we wouldn't do it." David: "Or couldn't do it. I remember meetings in which he said, 'You'll never fucking do it.' That's precisely what was said. Exactly that term...(laughs)...except slightly harder." (Rolling Stone, 1987) It became increasingly clear to Waters that Pink Floyd were attempting to continue. But this was not the end. There was a well-publicised court case to come, battling for control of the Pink Floyd name. As Roger himself was soon to find out, the name of the brand was bigger than the names of the bandmembers. Despite having offered Gilmour and Mason the Floyd name--in the belief they would never use it--when they did use the Floyd name, things got very ugly indeed. This band is my band Roger: "The Pink Floyd sham (is) a grand display that's also being excused in public because it makes for great arena rock: someday the world will know the depth of this entire hoax!" (1987) Whilst Roger was working on his soundtrack to When The Wind Blows, David Gilmour had also begun a new album, which, at some early stage became the new Pink Floyd. And what of the new Pink Floyd? Bob Ezrin, who had worked extensively on The Wall, had been invited by both Roger Waters and David Gilmour to produce the two separate albums. After some very brief work on Radio KAOS, Ezrin defected to the new Floyd project, then called Delusions Of Maturity. Michael Kamen, who had been Rick Wright's replacement throughout the recording of The Wall, The Final Cut, and The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking, had also been contracted by the Gilmour-led Floyd to again continue the role of Pink Floyd substitute keyboardist. Until his death in 2003, Michael Kamen remained in this role, performing all of Rick's parts as late as David Gilmour's 2002 solo shows (barring the Pink Floyd tours where Rick himself was present). The recording of A Momentary Lapse of Reason, though, was fraught with difficulties. Gilmour was trying to re-capture the sound that Pink Floyd lost in 1977, when Waters began to write the band's material almost exclusively. But without Rick Wright, and with Nick Mason's confidence at an all-time low, Momentary Lapse is a Floyd album in name only. (It is debatable whether Mason actually plays on the album, and the initial live video shot in Atlanta at the beginning of the Delicate Sound of Thunder tour was scrapped, as it was obvious that Nick wasn't doing much drumming, if any.) "After four to five months of constant work with Gilmour and company," said Roger, "Bob spoke to Michael Kamen, who did orchestral arrangements on The Wall and also co-produced my first solo album, The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking. Bob told him the tracks were 'an absolute disaster, with no words, no heart, no continuity.'" Michael Kamen, who had declined involvement at the start of the project, confirms Water's account of the conversation with Ezrin. (Rolling Stone, 1987). "On August 4 of '86," Waters adds, "I had a meeting with Dave on the Astoria, because we were still trying to settle our differences. Dave told me himself that he still had no respect for either Wright or Mason, but that they were useful to him." The Floyd carried on regardless. Gilmour and Mason brought in a supporting cast of supplemental musicians to mimic the Floyd sound. Roger continued too, this time bravely (or perhaps foolishly) competing almost directly against the Floyd. Roger was aided by 17 different session musicians, including former Floyd associate Clare Torry. Radio KAOS was released in June 1987. The Floyd--aided by 22 session musicians--released A Momentary Lapse of Reason some nine weeks later, and both parties embarked on simultaneous US tours. The Floyd played stadiums and multiple nights at arenas, and Waters followed suit, playing to often half-full US arenas a few weeks later. By the time the Waters tour ground to a halt at Wembley Arena in London, Pink Floyd were due to play two nights at the Stadium, 500 yards away and eight times bigger. Andy Fairweather-Low was joined on guitar by Jay Stapley, replacing Cambridge alumnus Tim Renwick, who had left Roger's band to play guitar with... Pink Floyd. The plot thickens. The Delicate Sound of Lawyers Roger: "I don't think they should be called Pink Floyd. I think it's a very facile but quite clever forgery. If you don't listen to it too closely, it does sound like Pink Floyd. It's got Dave Gilmour playing guitar. And with the considered intention of setting out to make something that sounds like everyone's conception of a Pink Floyd record, it's inevitable that you will achieve that limited goal. I think the songs are poor in general. The lyrics I can't believe. (chuckles ironically) I'm sure it will do very well." (Penthouse, 1988) There was never an uglier time than the Penthouse interview of 1988. Roger, having culminated his tour of sometimes-half-empty US arenas (with one venue having sold just 1,800 tickets of the 12,000 available) was at home, while his former bandmates were taking his songs and selling out every stadium, football pitch, and sports arena they could get to. And this is how the Penthouse interview started: "Is there anything more sad and unjust than a fake? Can you imagine the disappointment in learning you'd spent your savings on a false Magritte or a fraudulent John Lennon manuscript? Not to mention the spiritual trust and emotion people invest in the symbolic power of any name." To be fair to Roger, he wasn't using the Floyd name. But then again, his set was made up of just as many old Floyd songs, abetted by long standing Floyd associates. He was trading on his past as much as anyone else. The pot was calling the kettle black. Derailed from the stadium glories of his former bandmates (but still, according to rumour, receiving a 25% share of their total profits as severance, and those lucrative songwriting royalties), Waters set about writing his next album, Amused to Death. But he was still fighting a war of words, one that ultimately did him more harm than good: "From there, the story takes a sordid turn," claims Waters, "and after long thought on this mess and the mountain of falsehood that this scheming bunch has created, I'm now going to divulge the cold, hard, indisputable facts. Please do feel free to go back to any of the parties mentioned about their side of the story. I think you'll stop them dead in their sneaky tracks." The Bravery of Being Out of Range Now, pay attention; this is where it gets complicated. Following the Radio KAOS tour, Pink Floyd continued without Roger. By 1990, they had poached Clare Torry from Roger's band to sing with them at Knebworth. Meanwhile, Waters himself hosted a fair forgery of Pink Floyd by recreating The Wall in Berlin on its tenth anniversary, before beginning sessions for his new album. So Clare Torry leaves Roger and sings with Floyd. Tim Renwick also defected from Roger's band and becomes second guitarist for Pink Floyd. Meanwhil, former Floyd guitarist Snowy White replaces David Gilmour for an exact recreation of Pink Floyd's Wall show in Berlin. Michael Kamen, having defected to the Floyd in 1987 to replace an absent Rick Wright after spending five years working with Roger in his various bands, jumped ship once again, scoring The Wall Live In Berlin as well as Amused To Death. Amused To Death also saw the return of Pat Leonard to the producer's chair, fresh from his work on A Momentary Lapse of Reason. Snowy White also recorded with Roger for Amused To Death, appearing on all the demo recordings, only to be usurped by Jeff Beck on the finished product. Jeff Porcaro, who had played drums on Gilmour's About Face album, also played drums on one of Roger's songs. To complete the Amused to Death album, alongside the five former Floyd musicians and producers involved in the record, Gerald Scarfe submitted artwork for the record. The artwork was not used for the finished product: depicting three well-known musicians drowning in a champagne glass (one can only suspect that they called themselves Dave, Nick, and Rick), the artwork was a step too far even for Roger. Amused to Death For those of you who think (and, for the most part, rightfully so) that solo albums are generally at best only a quarter as good as records that feature the whole band, prepare to listen to the best record Pink Floyd never made. Amused To Death is a grand, brilliant statement. Based on the conceit of a future visitor to Earth seeing mankind as skeletons in front of long-defunct televisions, shadows burnt into the wall, and our species extinct through war-as-television, Amused To Death it hardly sounds like a boatload of fun. Then again, since when has being in the Floyd been fun? First, you won't ever hear an album that sounds so much like Pink Floyd in your life. Every Floydian trademark from their career is employed here: a slow heartbeat here, a well-chosen tape loop of someone talking there, the octave basslines, a soaring guitar solo or two, list lyrics, bird and locust sounds, backwards messages, duelling male/female vocals, and the use of the same speech at the open/close of the record. Sonically, the album was more Floyd than Floyd. One executive at Roger's record company is quoted as saying "If it had the words 'Pink Floyd' on the cover it would sell as many as Dark Side of the Moon". It starts like every Pink Floyd album has started for years. A slow, atmospheric, instrumental coda that echoes the central theme of the album. A heartbeat. An elegant guitar line. The sound of something distant. And a voice. A voice saying something, something unclear that slowly comes into focus. And then, Alf Razzell recounts a horrific experience carrying a dying man across No Man Land's in the First World War. Sounds like "Signs of Life", or "Breathe", or "Shine On You Crazy Diamond". Sounds like Pink Floyd. The plan was clear. If Amused to Death sold more than a million copies, Waters would take his backing band, again consisting of former Floyd associates and alumni, on tour to beat the Floyd once and for all. The album 'stiffed' at 500,000 copies on initial release. It is a figure that most bands would be overjoyed about, but when his failures (The Final Cut, for example, 'stiffed' at 4.5 million copies) are judged against The Best Selling Album of All Time (TM) in the shape of The Dark Side of the Moon, everything is a failure. The Division Bell After a three-year break from the limelight, Pink Floyd returned. The Division Bell featured many familiar faces. Bob Ezrin was back to produce. Tim Renwick, Roger's former guitarist who joined Pink Floyd in 1987, played on the album. Dick Parry, who played saxophone with the band from 1973-1975, returned for the album and the subsequent tour. Michael Kamen again returned to the group. I told you, it gets complicated. We haven't even got as far as Rick's solo album, Broken China, yet. The one Tim Renwick and David Gilmour played guitars on--though Dave's contribution (to "Breakthrough") was not ultimately used. Again, in a fair forgery of the Floyd, Pink Floyd had surrounded themselves with longstanding, familiar faces: people who had played with the band and with Roger for years. Roger, it seemed had fallen into a state of creative bankruptcy, tinkering with an opera and selling off old film cels from The Wall. Later on, Wall action figures would appear on the market, something which frankly stretched Water's credibility to breaking point. Regardless of what you think about the Gilmour-led Pink Floyd, they never did anything as crass as selling action figures. Sorrow Pink Floyd had always shied from being personality-driven, and had enjoyed the relative anonymity of a brand name rather than individual egos. For Roger Waters, going solo was a brave move, and one that ultimately backfired. People knew the name of the band, not his name. And despite his best efforts, the very thing that Roger wanted during his time in the band--shelter behind the name of his band--was the one thing that was his undoing when he left. Most people simply didn't know who he was. Roger: "It is frustrating to find out how many people don't know who I am or what I actually did in Pink Floyd. We get on a plane, and people ask what band we're in. I tell 'em I'm Roger Waters, and it doesn't mean a thing to them. Then I mention Pink Floyd, and they go, 'Yeah, 'Money'. I love The Wall.' "Oh, I wanted anonymity. I treasured it. And somehow we made it big and stayed private and anonymous. It was the best of both worlds. But now it's as if the past twenty years have meant nothing" (Rolling Stone, 1987). Roger took a risk, and it cost him. In the meantime, the war of words continued. In the public's eye, this mattered not. The Floyd were touring, and you could go see them. That must be worth a ticket, I reckon... At the time, Gilmour said this: "I don't see any reason why I should stop. It took decades of care and feeding for Pink Floyd to find its loyal audience, and I won't throw in the towel, especially after Lapse of Reason has been such a huge success. Roger doesn't have the right at present to tell me what to do with my life, although he believes that he does. And he'll not ruin my career, although lately he's been trying to." But who or what was Pink Floyd was still up for debate. Was Pink Floyd the band called Pink Floyd with three original members? Was Pink Floyd whatever Roger wanted them to be? Was Pink Floyd something else? Something intangible? A feeling? Goosebumps down your neck when the music plays? Nobody really knows. But Roger still took the moral high ground, claiming a moral victory even if he could claim no other: "The main difference between me and Dave Gilmour is that, when it comes time for him to finally confess his dishonest... venture to the world, I'll at least have the justice of a solid, credible head start on him." Waters shows a fatigued grin. "That's the advantage of putting your own good name on your work. If people do decide they enjoy it, they always know who to thank and where to find you." In the Flesh 1999 saw the return of Roger Waters to the concert stage, performing his first tour in twelve years. Posters proclaimed him to be "The Genius behind Pink Floyd", and utilised pictures of hammers, walls, pigs, prisms, and anything else Floydian you can think of. The tour lineup was oddly familiar. Jon Carin, co-writer of "Learning to Fly" from A Momentary Lapse of Reason, and a member of Pink Floyd's touring line up from 1987 to 1994, was brought in to again be Rick Wright's live doppelganger. Snowy White, in his twenty-third year of imitating David Gilmour, again became the band's guitarist. Roger reassembled his band of known and familiar faces, such as Andy Fairweather-Low, who'd first played with him 15 years previous. He also included some not-so-well-known faces behind the console: James Guthrie, who had mixed and/or produced The Wall live shows, as well as The Wall, Is There Anybody Out There?, The Final Cut, Amused To Death, The Division Bell, PULSE, Echoes: The Best of Pink Floyd, and Flickering Flame, was also on board, mixing the live shows and the subsequent live album, also titled In the Flesh. The simple facts are that you can take the man out of Pink Floyd, but you can't take Pink Floyd out of the man. No matter what Pink Floyd and Roger Waters did, both surrounded themselves with a close network of partners in crime, often borrowing members, players, and producers to re-create a fair forgery of Pink Floyd. Neither is better or worse, or more or less entitled to trade on the Pink Floyd name, but now, some 20 years after the event, there is no truth. We had what we had. The truth is in what we hear, what we feel. Neither party was a discredit to the Floyd legacy: just a different direction, a different presentation of the same idea. Roger: "There are no simple facts. We will all invent history that suits us and is comfortable for us, and we may absolutely believe our version to be the truth... the brain will invent stuff, move stuff around, and so, from 30 years ago, from 25 years ago, there's no way any of us can get to the truth.". It's only rock 'n' roll. But I like it.

You can take the man out of Pink Floyd, but you can't take Pink Floyd out of the man.