Features page 1 | Features page 2 | Opinion | Reviews | Brick By Brick | Speak To Me

Featured Images | Gilmour, Guitars & Gear | KAOS Theories | Trivia | Puzzles| Humor

The Light was Brighter

Pink Floyd's lasers light up the sky

Of the many memories from the Momentary Lapse of Reason, Delicate Sound of Thunder, and Division Bell tours, few have etched a memory more vivid than the pristine, crackling laser lights emanating from the throne of our heroes. While Mr. Screen, films, various high-tech Vari-Lites, beautifully choreographed stage lighting and DMX mastered effects were wonderful, they seldom evoke the same emotional and fanatical memories and discussion as the lasers.

Marc Brickman, set designer for both the 1987-89 and '94 tours, chose to incorporate lasers in his designs to round out the range of technologies at his disposal. In this process, the designs were left to subcontractors to work into Brickman's vision. This decision being made, the process having run it's course, the fans witnessed the fruits of much labor, not to mention expense.

When interviewed by Lighting Dimensions Magazine for their January 1988 issue, Marc Brickman had this to say regarding his vision to use lasers for the Momentary Lapse of Reason tour:

A Division Bell tour stop. |

"Because there's no overhead truss, and there's a wide open area over the stage. Every time I see lasers used, they seem to be doing some kind of scanning graphics. For this show, I wanted very big, architectural-type monolithic structures over the stage. What we've come up with are these really pretty beam sculptures, static looks that become part of lighting and the look of certain songs. I feel they're more powerful that way than when you flash them and do moving beam tricks."

Mark Grega, laser operator for the Momentary Lapse/Delicate Sound of Thunder tour was part of the team tasked with carrying out Brickman's ideas. (The entire interview with Mark Grega is included below.)

"The main focus of Brickman's design was lots of colors. He also pushed LaserMedia to come up with a cross-fading controller for the systems that could also handle cross-fading color. The LaserMedia IMAGEN Computer couldn't do a cross fade and Marc Brickman really wanted [it]. If you watch the Momentary Lapse video and the song "On the Turning Away" you can see what he was looking for." Grega continues, "As far as beam sculptures, Scott, Peter and I designed where the beams were going and bounces. MB wanted to do lasers bigger than anyone had done before so there were two Full Color Systems."

For the Division Bell tour, Brickman wanted to retain what had worked in the past, thus propagating the Floyd concert legacy of musical and visual extravagance, while enhancing the show by making use of the very latest and greatest technologies at his disposal. But for Brickman, that doesn't always mean technologies "currently" available to the entertainment industry, and sometimes he has to look outside the box to fulfill his visions. When interviewed for Lighting Dimensions' September 1994 issue, Brickman comments on his laser upgrade for the new tour after a trip to Hughes Aircraft:

"Being an American, I listen to all the propaganda that our news media puts out, so as they said something about how they were reducing the defense budget and trying to turn the defense into commercial applications, I figured maybe I could go out and buy some "Star Wars" lasers," Brickman says. "And at the time that I was doing that I got a call from Mark Loman at Rocklite describing this laser. So, I went out to Toronto and saw it, and thought it was great. And I have 2 complete, 50W, copper-vapor laser systems."

(In fact what the Floyd bought for the 1994 tour were two Oxford Laser ACL 45 Copper vapor lasers. The ACL 45 is a big laser. The laser heads are 2.526 meters (99.4") long by 28.2 cm (11.1") by 37.0 cm (14.6") and weigh 145 Kg (651 lbs.); the power supply units are 67.5 cm (26.6") by 65.2 cm (25.7") by 75.9 cm (29.8") high (including the wheels) and weighs 230 Kg (506 lbs.) These units give 45 watts of laser output each from only about 7Kw of electrical power.)

Laser operator Warren Toll comments on Brickman's choice of laser for the Division Bell tour:

"We have 2 complete systems, but if Brickman had it his way, we'd have 6 or more. They're really expensive lasers, about $120,000 apiece, and that's just for the laser and the power supply, not including all the other electronics and hardware that we require to run a creative-looking show."

But what exactly is a laser show? How do they get all those beams at once? How many "lasers" did Floyd use in their shows? What kind of lasers did Pink Floyd use? And how much does all this cost?

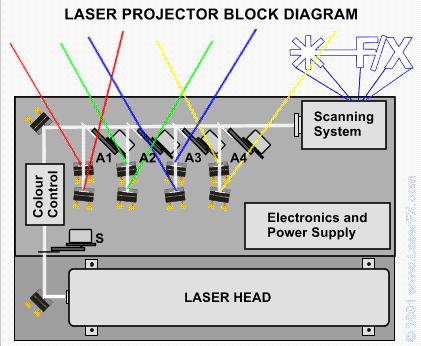

A laser show consists of three basic components: the laser, the projector, and the controller. There are also remotely mounted mirrors and theatrical fog to contend with. But first let's go over the basics.

When you look at a show and see dozens of beams bouncing all which ways, sometimes in different colors, there are typically only one or two actual lasers in use. The laser is the device that produces a single beam of cohesive light. Webster defines laser as: "a device that utilizes the natural oscillations of atoms or molecules between energy levels for generating coherent electromagnetic radiation usually in the ultraviolet, visible, or infrared regions of the spectrum." As defined by the name, actually an acronym, a laser is Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation.

The laser 'beam' is directed through optics which focus or 'collimate' the beam through a shutter, directly into the 'Laser Projector'.

|

Projectors vary widely in design, but generally consist of optics, mirrors, actuators and shutters which select colors and or effects, and direct the beam according to the needs of the show. One of the main components of the laser projector is 'scanners'. 'Scanners or 'Galvanometers' (galvos) are mechanical devices which have a small mirror mounted on a shaft which rotates in an electronically controlled arc. Two scanners are typically employed perpendicular to each other to control the X- and Y-axis of beam direction. By using scanners and their associated control electronics interfacing with a computer or other controller, the beam is directed faster than the eye can detect between the different components on the projector which directs the beam we see in the show.

The result of this rapidly moving beam is the appearance of several apparently "simultaneous" beams of light for the designer to direct at remote mirrors or other optics, effects, or out into the sky or venue, above the audience.

The controller is typically a computer or similar lighting control board, from which the operator can control the show, and the direction, color, intensity and switching of the beams.

Remotely mounted mirrors such as those on the stage and lighting trusses are used to reflect and direct the beam per the show design. Fog machines are used to enhance the appearance of the beam by introducing particles in the air which the laser light illuminates and scatters, making the beam more visible in open air.

With the mechanics of the "Laser System" described, the rest is in the hands of the designers and operators to integrate into their show. For the Floyd tours, Brickman chose to integrate "Beam Shows" into his design. "I guess I have to take responsibility for the design and look of the show because what you see--the choice of equipment--was based on what I saw in my head all along," Brickman says. "But you can't do it without a team. They protect me. I take all the credit and they do all the work."

In the past, lasers used for concert lighting have used some standards based on the technology typically employed. For example on the Momentary Lapse tours they used 2 Spectra Physics 171 Argon Lasers and 2 Spectra Physics 171 Krypton Lasers through two Laser Media projectors. The Argon and Krypton SP 171 lasers are pretty standard fare for laser shows, the argon producing the higher-powered blue/green beams, and the Krypton lasers for red. The beams could be combined through Polarizing Cubes to produce other colors.

A barrage of laserbeams wows fans in 1994. |

While the architectural 'beamscape' designs were essentially the same for both tour designs, for the Division Bell tour the scale had to change. Brickman's pursuit actually forced an advance in the standard employed through technology.

The use of the word 'standard' in this context refers to the diameter of the beams. According to Brian of Cambridge Laser Labs, the SP 171 Argon and Krypton lasers used for the Momentary Lapse employed a beam diameter of 1.6mm. The optics used in most projectors were sufficient for this tour. For the Division Bell tour, there were some limitations to consider around the choice of laser. The Oxford Laser ACL 45 Copper vapor lasers beam diameter was 42mm! (about 1-5/8"). This is a very large beam for entertainment systems, and in fact would 'overfill' (the beam diameter was larger than the mirrors on the scanners) available projector system optics.

Division Bell laser operator Warren "Wiggy" Toll, part of the team tasked with carrying out Brickman's laser vision, talked about the new lasers and some of their challenges in 'Lighting Dimensions':

"These lasers have never been used in this application before; they're used mainly for high-speed photography and nuclear research. Marc was most intrigued with the power output, which is substantially more than a standard argon laser system that is primarily used in this application."

What this meant was that for the Division Bell tour, they had to build new projectors. "Although we've had quite a lot of laser experience, we weren't used to using a laser that put out a beam of that thickness," Toll explains. "In and before rehearsals, we had to design a new style of projector and a new way of actuating the beam or switching it into different channels."

Rocklite of Toronto retrofitted their standard projector design to work with the new lasers. They added larger mirrors, Galvos, and optics to new projectors, and came up with new adjustments and effects to accommodate the larger and more powerful beams from the ACL 45 lasers.

"We had a brilliant light source, but we couldn't do anything with it unless we found out a new way to switch it," Toll elaborates. "Rocklite is the first laser company to use these lasers and Pink Floyd is the first tour to ever incorporate these types of lasers into a show. They've really just been used for lab research in the past--they've certainly never been used in rock and roll, but I guess Pink Floyd is a good place to start."

Millions of fans would tend to agree.

Another benefit of the new lasers was the colors produced at higher power levels. Toll continues, "Also, the colors that we could achieve from this Laser are a yellow-gold line and also a green. The raw power of it, the size of the beam, and the colors are different from those in an argon system."

Beam color is a product of the wavelengths of laser light produced. One limiting factor in the traditional Argon and mixed gas lasers is power. When a laser beam is filtered or 'selected' for a specific color by the projector optics, significant power is lost. The new ACL 45 lasers have enough power to compensate for this limitation to an extent, offering more vivid color choices to the designer.

The ACL 45 lasers produce two wavelengths simultaneously (multiline), emerald green at 511nm and yellow at 578nm, together producing a gold hue at 45 watts. In addition to having more colors available in the Copper Vapour beam, the ACL 45's 'pumped' dye lasers to produce the vivid red colors used in the Division Bell show. Dye lasers are used to change the wavelength, or color of their source light. In this setup, the source being the ACL 45s, the beam was directed through the dye laser, which was tuned to produce the very nice red 620nm beams. With the dye laser, 30% efficiency was realized to output approximately 15 Watts of red beam.

For any laser show in the US, the CDRH regulates the use of lasers. The CDRH, or Center or Devices and Radiological Health, a division of the Food and Drug Administration, requires laser show operators to have an approved 'Variance', which is basically a government permit for laser show operation. The CDRH must be notified of each performance and the operator's variance for each Laser System--including the laser, the projector and the intended use--must be listed. For outdoor venues this also includes intended beam paths for coordination with the Federal Aviation Administration. The idea is that Notices to Airmen (NOTAMs) be issued for each Terminal Control Area affected by the potential path of laser beams.

A brief mention of laser safety is in order. Laser beams can burn at close range, and cause blindness at longer ranges, including burning of the retina at these longer ranges. I have seen and felt this first hand. While setting up projectors, I have had clothing burn, as well as discovered my finger in the beampath in time to avoid a burn, but it doesn't take long. Some laser operators are fond of lighting cigarettes in the path of the light. The Momentary Lapse video shows Laser Crew Chief Scott Cunningham doing just that! Pilots looking directly into the beams could potentially be blinded, which would be 'not good' for the passengers in their airplanes, nor for the people under them. A spokesman for Oxford Lasers, Rick Slagle, comments on the American debut of the Division Bell tour:

"With a similar divergence to argon lasers, a Copper Vapour laser beam keeps its size for long distances. One consequence of this is that when the tour is playing at open-air venues and is projecting unterminated beams, it has to work with local Air Traffic Control to declare an exclusion zone around the stadium. This isn't always too effective--at the first show in Miami last spring, the local airport's control tower put out an "all points bulletin", warning pilots to keep away from the Dolphin's stadium. Within half an hour we had the Pink Floyd Blimp, two light aircraft and a helicopter circling overhead."

(Divergence refers to the tendency of a beam to spread in diameter as a factor of the distance it has traveled. The ACL 45 beam, being state of the art for entertainment systems, provides a powerful and potent beam. The "all points bulletin" refers to the NOTAMS issued by the FAA.)

Mark Grega comments on FAA dealings in Florida, USA during the 1987 tour:

"FAA was for the most part not a problem. Orlando was I think the only city that made us terminate all beams, even scanning. It was also my hometown at the time and quite a bummer for the home team. We also lost an Argon laser that day on the truck ride so it was a red show to add injury to insult."

('Beam termination' refers to having a 'backstop' or a solid surface like a wall or mirror that the beam does not pass through. In other words, they weren't allowed to shoot the beams out into the sky.)

Well, all this tech talk is fine and good but what about the show? As a laser enthusiast, I thoroughly enjoyed both tours. I do recall the indoor venue for Momentary Lapse at Oakland, California, I attended two nights. The colors and beam effects were vivid and bright. I wouldn't exactly call it 'disappointed' but I did wonder why there were no graphics. I knew what could be done with laser graphics, and was perplexed why the Floyd didn't use them. Mark Grega's explanation along with the Brickman interviews explain that decision to me.

Most impressive to me was the fading in and out of the colors and beams. I talked to Mark Grega about this and he said they did quite a bit of work on the controller to get this to work. The effect was done with a combination of varying the laser voltage and the fader on the controller. They would cross fade from one color to the next as well as fade the beams in and out.

Watching this fading as a fan, I was impressed with the illusion it seemed to produce. This of course was enhanced by my choice of personal visual aids. The beams would start out with a barely perceptible line, and ever so slowly become one of Brickman's 'beamscapes'. This was all choreographed with the lighting on Mr. Screen, sometimes with the Floyd Droids, and sometimes alone.

From the Division Bell tour, I was very impressed with the power and size of the beams. The scanned effects were also the brightest I'd ever seen. The bounces and patterns were a worthy enhancement to my favorite live music. Again I wondered at the lack of graphics, but there were so many other things going on, I see Mr. Brickman's point.

If the boys ever grace us with another tour (I'd love to be on board, Mr. Brickman; you know where to find me), I've got some ideas of my own around lighting up Mr. Screen in a wreath of laser light, and some ideas for graphics that would work in the big picture. I'd also like to see CDRH approve audience scanning with more ideas of my own for us fans in that area, but that technology takes money and work. Pushing the state of the art has never intimidated our band, if anybody can do it, Floyd can.

Someday, maybe we'll get another slice of heaven, under a Brickman beamscape. Until then Think Pink!

The author would like to acknowledge the following persons and organizations for their contributions to this article:

ILDA - International Laser Display Association, great people who were very helpful, without whom there would be no article.

LaserFX, a wonderful company dedicated to all things laser.

Lighting Dimensions Magazine

Mark Grega

Tim Walsh

Walt Meador

David Kennedy

L. Michael Roberts - yes, it helped :-)

Mark Reilly

Dan Lawrence

Brian at Cambridge Laser Lab

Pink Floyd

An interview with laser operator Mark Grega

Through some days of phone tag and an email volley, Mark Grega of LaserFX was kind enough to grant me an interview. Mark was the laser operator for the Momentary Lapse and Delicate Sound of Thunder tours. Here is the interview in its entirety, from February 23, 2003.

Mark Jacoby: Which tours were you with?

Mark Grega: "I toured with Pink Floyd for the Momentary Lapse of Reason and Delicate Sound of Thunder World Tours, 1987- 1989. Japan, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Russia, and the US were just some of the places we played.

Momentary Lapse had a crew of 4: Scott Cunningham (Laser Operator/Crew Chief), Peter Callagan (Laser Tech), Scott Ritt (ColorRay Tech ML), and myself (Color-Ray Operator & Laser Tech). Delicate Sound of Thunder had a crew of Cunningham, Callagan, Joe Androff (Color-Ray Tech DS), and myself. Craig Speaderman (Laser tech DS) was with us for a leg in Europe and we had another guy Vazaly for another leg."

MJ: Could you describe any interaction you had with the Design process?

MG: "As with most tours, it starts with the Lighting Director (Marc Brickman) and meetings with him and the touring LaserMedia's staff. The first tour was special because of the introduction of the COLOR-RAY's. These were Xenon light sources that fed fibers up to a special Vari-Lite head. There were four of these units that we called DROIDS. They had names given to them by Marc Brickman (Manny, Moe, Jack, and Floyd). The first three names were from an automotive stores in California and their mascots and the fourth is... obvious. The main focus of Brickman's design was lots of colors. He also pushed LaserMedia to come up with a cross-fading controller for the systems that could also handle cross-fading color. The LaserMedia IMAGEN Computer couldn't do a cross fade and Brickman really wanted [it]. If you watch the Momentary Lapse video and the song "On the Turning Away" you can see what Brickman was looking for. As far as beam sculptures, Scott, Peter and I designed where the beams were going and bounces. Brickman wanted to do lasers bigger than anyone had done before so there were two Full Color Systems.

The lasers, seen here in 1994, had to work within the context of all the other visual elements. |

We threw some laser graphics together and showed them to Brickman and Dave, stuff with the pig and other Floyd symbols. Dave and Marc would go off alone and talk about things like that. They decided the video looked better and said no to laser graphics.

MJ: What equipment was the laser crew responsible for?

MG: Laser World

2 Spectra Physics 171 Argon Lasers

2 Spectra Physics 171 Krypton Lasers

2 Spare Tubes

2 Spare 171 Power Supplies

4 480v Buck Boost Transformers

1 Main Power Distro

2 LM Projectors (I can't remember how many positions they had, I think 12?)

2 Sets of GM100 Scanners (12K)

2 Polarizing Cubes for combining the Argon and Krypton beams

2 FiberRays (LM fiber fed scanning projector) (We had to use 2 in case a fiber burned, which they did all the time.)

2 LM IMAGENS

1 IBM Cross Fading Computer

1 RhineStone Rotating Ball that was fiber fed (One of These Days)

4 Teel Water Pumps

lots of 8" Front Surface Mirrors

tons of Water Hoses

miles of 4/0 feeder cable

100mc fiber was used for all effects

Color Ray World

32 Color Ray Units

1 Signal Decoder (signal was sent via LED down a fiber)

1 Signal Transmitter

1 Apple SE Computer (Out Front of House)

1 ColorRay Computer Rack (This rack had 32 individual Computers for each output)

miles of 1000mc fiber for the light transmission to the head ("tree trunks", as we used to call it)

MJ: What projectors did you use?

MG: These projectors were the typical LaserMedia system. The lasers were contained underneath the main projection breadboard. This is where the color mixing was done. The beam then came up to the top of the projector and then down to a target at the end of the projector. (clear) There were GM10 actuators that came into the beam path and diverted the beam to splitters and then on to MM1's. These projectors were very crude but very reliable. They also had a ton of specular reflection due to the fact that the beam traveled down the top of the table, so we constantly had to create Foam Core covers to contain the splash. These were called "condos" by all of us on the crew. Depending on how many shows we were doing in a certain city would depend on how many "condos" we had to make. These were square boxes that covered the entire top of the table and then we would have to cut little holes for each beam position. By the time we were done, the cover would have a million little holes that looked like windows. These would last anywhere from one to two cities. Sometimes we would push that number to three or four or until we started a little fire on the projector and had to remove it during the show. That was always a lot of fun (panic).

MJ: What was a typical day in the life of the laser crew?

MG: The most wonderful thing about being on tour with PF was that there never was a typical day. We did some incredible shows. The Grand Canal in Venice. The stage was on a barge and was floating in the middle of the Grand Canal and we played to a million people on shore. (They trashed the city and the mayor and 12 city counsel members were fired because of it.) The Palace of Versailles. They setup shop in the middle of the Avenue De Paris and did three shows to 200,000 people each night. For that show we brought in three other complete laser systems from the USA and did the show with 360-degree laser effects. ("Great Gig in the Sky" on the Momentary Lapse video) That was one of the best nights to be a laser guy. Moscow was amazing. Modena, Italy was very cool because we did that show so that Dave, Nick, and Steve O'Rourke could buy F-40 Super Sports Cars. I had Enzo Ferrari sitting next to me front of house.

Back to a day in the life, mirrors had to be put on first thing with the lighting crew and the installation of the trussing so Scott Ritt had that duty. The rest of us would still be sleeping on the bus. Wake up, eat breakfast, and then unload the truck. I think we had altogether about 70 road cases for lasers and Color-Ray World. We took up about one-third of a regular semi-truck trailer. We would get about four stagehands to help us with the dirty work (hose and feeder). We would have them start on running those things while we started getting everything out of the road cases. The lasers lived in road cases to protect them from the bumps. (On a ride in Australia, we lost 4 tubes because of their roads. That was a bad day for LaserMedia. Spectra loved it! Four new tubes at $12,000 each.)

So each day we had to touch, tweak and clean each laser for maximum output power and then insert them into the projector. Then we would have to clean the projector and get ready for water. Water and high voltage has always been my favorite thing about 171's. Once water and power were happy we would align the projector and target the mirrors. Then I would climb up into the trusses and do the focus. We had the high beams for "On the Turning Away" and the main beams on the circle truss. Then we would focus the scanners and fibers and then get ready for the show. It took about six hours for us to be show-ready.

Outdoor stadiums presented their own unique problems. Mostly rain. For about three years, we couldn't say the R-word. If we said it, it would rain. All of us made up T-shirts that said "PINK FLOOD". Wherever we would go, it would rain. Outdoor focuses are tough because of that great big thing in the sky. We almost never had a pre-rig day so load-in was also show day. It was almost impossible to see a 12-watt beam in Miami around 2pm so we had to work with the lasers at full power to even see them.

Show time was, of course, what it was all about. We could have the worst load-in but the show always made up for it. To hear 50,000 people collectively go "ohhhhh" was worth it. There were some truly beautiful moments in those shows. "Wish You Were Here" with the SR beams first during the vocals and guitars and then the SL beams came in with the song. "Comfortably Numb" with the WAVE. "Run Like Hell" with the mayhem on Dave during the opening guitar part to "WARP 10" as Brickman used to say when the song really got going and everything was going at full tilt.

"Welcome to the Machine" was my personal favorite. The Color-Ray system was computer controlled as far as scanning and what images were used but it also had a manual console to 'play' certain elements live. Scan speed, gain X & Y, shutter, etc. Each night I got to play along with the band and that was always amazing.

Back to the question, the show was about two-and-a-half hours long, and then came the load-out. Load-out took about one-and-a-half hours for everything to make it back into the truck with the exception of the mirror cases that lived on the lighting truck. The laser boys would almost always be the first ones to the bus. If not us, then the back-line guys but that's not bad. We had a great crew. We worked hard and we partied HARD.

MJ: What types of technical difficulties did the laser crew encounter?

MG: Wow, that's a rough one. There is a line out of Blade Runner that we used to use all the time. "I seen things you can't even imagine" with lasers on Pink Floyd. I seen flames shoot out the front of a 171. I seen a 171 turn into a waterfall and have 80 p.s.i. worth of water pouring out of the front and it was still on. Huge buck boost transformers with direct shorts. The huge capacitors in the 171 blow up and the power supply will jump about a foot into the air. I've seen stretch limos, huge front loaders, and even tour buses park on our drain hoses and blow things up. I seen four dead 171s all lined up in a row and Peter and I doing tube transplants hours before a show. You name it, I've seen it. Most of what happens on the road with equipment relies on the company you work for having the brains to send you out with lots of spares. On Floyd, we had lots and lots of spares.

MJ: Were Midi or DMX interfaces used to interface with the lasers?

MG: The Color-Ray systems did use Midi for control of the units. The laser systems were still controlled by the IMAGEN and did not use DMX. An RS232 cable had to be run for each projector as well as a 9 Pin for scanning information.

MJ: How were power and cooling handled?

MG: Power in the States was easy: 3 phase 500 amps. In Europe and Asia, the tour had generators for everyone's power needs. All the stadium shows had generators as well. Pittsburgh was a bad generator day. During the setup, the stadium made the generator crew park all the generators underneath these walkways and during the show, so one after the other over-heated and shut down. First we lost the lights and then about two minutes later we lost the sound. It took a little while to get the show back up and running but the show did go on.

Water sucked. It always does. I think we had 4 road cases with just hose. Black for in and Red for drain. I think we carried about 2000 feet of hose, 500 feet for each system. Those hoses feed a TEEL brand pump that knocked whatever water pressure we had up to the 80 p.s.i. that we needed."

MJ: How was it working with CDRH and FAA in the USA?

MG: New York City is always fun because of the laser license. But over all, we mostly got inspected either in state capitals or if the inspector really wanted to see the show. We had to have our checklist filled out and a copy of our variance. They would want to see the beams and hang out on stage.

FAA was for the most part not a problem. Orlando, Florida was I think the only city that made us terminate all beams, even scanning. It was also my hometown at the time and quite a bummer for the home team. We also lost an Argon laser that day on the truck ride so it was a red show to add injury to insult.

MJ: What was the Band's attitude like towards the crew?

MG: The tour had a nice feel to it. Some of the crew from previous years commented that it was a lot less stressful touring without Waters. Everybody was in great spirits.

They all had a great sense of humor. Especially Dave. The stage under his area was a grating to allow lighting and fog and stuff from underneath, and he could see through. During one song in particular, I can't remember which one, the one where the bed comes down ["On the Run"] Dave didn't have a lot to do. Dave would always look to the right, then down just before he starts playing again. I don't know why, he just does. So, some laser crew were always under there and during this part one night when Dave would start playing after the bed came down, he looked down, like always, and one of the guys had a toy blow up guitar and was playing air guitar mimicking Dave. He cracked up and missed a couple notes with about a half second of silence. After the show he talked to us and said not to do that anymore because it was messing him up. So a couple days go by and after another show he asked how come we weren't messing with him anymore under the stage. We told him "because you asked us not to" and he laughed and said he really liked it and it was OK.

After that, we would do things to try and crack him, like having blow up dolls under there during the show, blow up palm trees doing goofy shit. We would sometimes bring strippers under there flashing Dave during the show. We did other things too, one night we filled the pig's dick up with water so when it went out over the audience he was pissing on the crowd. Dave really cracked up on that one."

MJ: What was your overall impression of your time with Floyd?

MG: The three years that I toured with Pink Floyd were without a doubt the best. The music, the band and most of all, the crew made it what it was.

The Shadow of Yesterday's Triumph

One fan's recollection of the 'good old days'

Elliot Tayman was, at one time, one of the most sought-after Pink Floyd experts in the US. He worked tirelessly as the official US representative for Floyd fanzines The Amazing Pudding and Brain Damage. He became one of Columbia Records' "go to" guys, and was a key source of Floydian facts and history for countless radio stations, journalists, and authors. His position once landed him an interview with Entertainment Tonight, as well as invitations to release parties for both Columbia and Capitol Records, and an invitation to witness the Floyd's induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996.

And although his 'official' work for the Floyd community only began in the late 1980s, like many fans he has been following the band since the mid-70s. In this first part of a multi-part interview, Elliot remembers how he fell in love with the Floyd.

Spare Bricks: When did you first hear of Pink Floyd?

Elliot Tayman: Sometime in mid-1974, when I was a mere 14 years old. I was hanging around with a group of people who were into dance music. What I would call pre-disco. So naturally I followed them in their taste of music. But I always felt I was missing out on something.

One afternoon I was browsing through a record shop with a friend. He suddenly pointed to an album up on the wall. An album with a simple yet interesting cover. An all black background with a colorful prism. He went on to say, "I heard that album at a party the other night. It was fantastic! Take my word for it, you'll love it."

"What group is that?", I asked.

He replied, "Pink Floyd".

"Pink who?" I asked.

"Pink Floyd," he stated again. I never heard of them. What the heck, for $4 I took a chance and bought it. I took it home, popped it on the old turntable, and was completely blown-away! 'Fantastic' was putting it mildly. Little was I to know it was about to change my life forever. Gone were the days of dance music; hello rock and roll!!! I soon discovered other great rock bands like ELP, Led Zeppelin, The Who, Genesis, Yes, etc... I found my taste to be in the area of psychedelic rock. All I can say is thank God for this discovery. Because a few months later that awful disco music hit the scene.

Pink Floyd at Madison Square Garden, July 1, 1977. original photos courtesy of Elliot Tayman |

SB: What was the first time you saw a Floyd performance?

ET: My first Pink Floyd concert was on June 17, 1975 at New York's Nassau Coliseum. I had already attended a handful of concerts earlier that year, bands such as Bad Company, Led Zeppelin, and BTO. When I began to hear the spot radio announcements for the Floyd gigs, I knew I had to go. I figured I'd certainly hear "some" of Dark Side of the Moon and for this reason alone, I had to be there. I knew I'd see a good show. But I really had no idea what to expect since I never read anything about their previous shows. I guessed I'd be seeing a similar-type show to my earlier experiences with other concerts. Only I'd be hearing better and more enjoyable music.

SB: What do you recall about the Floyd's show that day?

ET: At 43 years of age, and 28 years later, it's very hard to remember all the details of that concert. But I vividly remember hearing the entire Dark Side of the Moon album. In that era, Pink Floyd was still a relatively faceless group. I paid more attention to the music than the members of the band.

I was completely blown away by the sheer magnitude of the visual light show--especially that unique round screen used for all the background film footage. I'd never seen anything like it before. Having bought only one other Pink Floyd album (Meddle) prior to the concert, I therefore only recognized the music played from the two albums I then owned. I left the concert totally in awe.

SB: What were your impressions of the visual presentation?

ET: Two words can best describe what I thought of the visual presentation--fantastic and unique. It definitely added to the overall enjoyment of the concert, but never distracted me from the incredible music. It actually made it better! As I stated above, I didn't mind being distracted from the band members themselves. If it weren't for the inside of the Meddle album cover, I wouldn't even recognize them if they were walking down the street.

SB: Do you remember any specifics? Inflatables, films?

ET: I don't recall any inflatables being used at this concert. However, I do remember the airplane on a guide wire which traveled from the back of the arena and crashed into the stage during the end of "On The Run". Timed perfectly to the crash was a film sequence shown on the round screen where a pile of Dark Side of the Moon album covers exploded. If I remember correctly, which again is difficult, the only film footage shown was during the playing of Dark Side. Though many books written on Pink Floyd contradict me. I clearly remember the same well-known films used when they played Dark Side of the Moon in its entirety during the 1994 tour. However, the film shown during "On the Run" was entirely different on the 1994 tour. If any films were shown during the other songs I just don't remember.

As for the lighting, it was far different from the few previous concerts I attended earlier that year. The typical lighting towers on both sides of the stage were in place. But they also incorporated lights around the edges of the giant round screen. They also presented the audience with a giant, round, mirrored disco ball which, when lights shown on it, reflected small points of light all over the arena. I had never seen anything like that, and never did again (until two years later when I saw the Floyd on the Animals tour).

Leaving the concert arena I realized I had just seen something very special. Unfortunately, I was just too young and not yet turned on to Pink Floyd during their incredible 1972-1973 tour. I always dream of going back in time to witness their gigs at Carnegie Hall and Radio City Music Hall.

SB: Fast forward to 1977. The Floyds now had a couple more hit albums under their belts, and were shooting for new heights of concert excess. What were you expecting when they came back to town? Did the band meet those expectations, or fall short?

ET: The first show I attended on the Animals tour was on July 1 at Madison Square Garden. I had read numerous reviews of their concerts from other cities, so I had a fairly good idea of what to expect--lots of lights, films, dry ice smoke, and of course the music itself. The band did meet my expectations, exceed in some areas, and fall short in other parts of the concert.

SB: The 1977 shows were a lot busier in terms of visual presentation--inflatable family, pig, etc... Was it too much, or just right?

ET: This was definitely busier than previous tours. Not only did they have to meet the fans' expectations in terms of music, but they now had to be concerned about the new inflatables presented on this tour--timing their appearances to certain parts of the songs and so on. There was also an ever-present worry about what to do should one of these inflatables suddenly spring a leak. I'm sure that every fan in the arena had his or her own opinion as to whether or not it was too much or just right. For me, it was just right. It seemed to fit nicely to the theme of the Animals album. But I was happy not to see the re-appearance of any inflatables during the performance of the Wish You Were Here portion of the concert.

The Floyds contend with smoke, lights, and fireworks at Madison Square Garden. |

SB: The band had also turned away from a free-form, improvisation-oriented band and was now performing the same show night after night after night. Did this seem to take the spark out of things? Did the band seem uninterested at all?

ET: Yes, the band was now in a very rigid form of performing. Certainly the task of having to time the music to the appearances of the inflatables prevented the band from straying from the established setlist. They also had to time everything to the films and light sequences.

SB: For the first time ever the Floyds were touring a show made up entirely of music they had already recorded and released. Even much of the 'new' music had been performed in 1975, although this was the first tour for some of the Wish You Were Here material as well. Did this bother you at all? Did you notice?

ET: Although I always enjoy hearing the Animals and Wish You Were Here albums played in their entirety, it did bother me knowing I would definitely not see them play anything prior to Dark Side of the Moon. Up to this point I still had not seen them play any material from albums released prior to Meddle. Considering this fact, of course I noticed. By now I owned all their albums up to Animals.

I saw three of the four Animals concerts at Madison Square Garden that week. After the second concert I yearned for the chance to see the band play something different on my final night there. The spark of the first two concerts was not present for me on the third night. I fully knew what to expect. Though still a fantastic show, it would have been wonderful to see something out of the ordinary. As for the band themselves, by this point on this long and grueling tour, the look on their faces said it all--especially Roger Waters' face. 'Let's just finish out this tour and get back to England.'

1977 performances of "Welcome to the Machine" were accompanied by films animated by Gerald Scarfe. |

SB: Wish You Were Here is an amazing musical suite, and yet relatively little has been written over the years about the accompanying concert visuals. Gerald Scarfe's "Welcome To The Machine" animations are horrifying yet beautiful. I've seen the 1994-era film for "Shine On", which made heavy use of Barrett-influenced imagery. What did they do for "Shine On You Crazy Diamond" in '77?

ET: Bear in mind the 1977 concerts are only two years more recent in my memory than the 1975 concerts. So still it's a bit difficult for me to remember every aspect of these concerts. But I do remember that during the playing of the second half of "Shine On You Crazy Diamond", a brand new film sequence by Gerald Scarfe was shown on the huge circular screen. It was of a vertical, free-standing, naked and faceless man. He began to somersault through the air eventually transforming into a leaf and then back again to a man. The screen slowly blacked out by a huge, mirrored disco ball which re-appeared after its initial use on the previous tour.

SB: How about "Have A Cigar" and "Wish You Were Here"?

ET: There weren't any films or visuals of any kind. Only the typical concert stage lighting and spotlights.

SB: As you mentioned, these shows were literally at the tail end of a long, grueling, unpleasant tour. The audience was rowdy, and Roger Waters was famously surly towards them. His outbursts, as much as the performances themselves, make the shows memorable 25 years later. What were your reactions to these outbursts back then?

ET: I was now 16 years of age and had a better understanding for self-control. So I could understand just how Roger Waters felt while he was playing in an arena where every now and then we'd hear a firework going off. This was during Independence Day week, and fireworks displays are a normal part of the celebration.

But not only is the use of indoor fireworks dangerous, it's quite annoying to hear just a loud boom as opposed to the band's use of brilliant pyrotechnics. I don't blame Waters at all for suddenly halting the show and subsequently announcing that he'd stop the show for good if the use of fireworks continue. Every time I heard a boom I could only shake my head in both anger and fear. Anger because I knew Waters might leave the stage and not return; fear because I didn't want to get injured by an M-80 explosive.

SB: How did the rest of the crowd react to the fireworks, and to Roger's outbursts?

ET: Looking around at nearby fans, I could clearly see that most would agree with the way I felt. Sure there must have been a few in the arena who enjoyed both the occasional firework and Waters' outbursts. I'd have to say they were younger then me or just stoned out of their minds.

SB: Was there any sense that you were witnessing something out of the ordinary? Or was this par for the course at Madison Square Garden?

ET: I don't feel that I witnessed anything so out of the ordinary. Nothing at Madison Square Garden was par for the course. Every concert or sporting event I had attended over the years at MSG was different from the previous one.

SB: Did Roger's outbursts distract you from the show? Is it possible that the band's reliance on so much visual spectacle took your attention away from the bandmembers themselves enough that you didn't notice their exhaustion, and their disgust at the audience's behavior?

ET: Any outburst from a member of the band you're there to see will distract you from the overall show, especially when the artist or band abruptly stops playing. But as always, the scale and magnitude of Pink Floyd's visuals will always draw one's attention away from the band members themselves. Even in 1977 I felt they were still a faceless band. After the release of Meddle their faces didn't appear on an album cover again until 1987. Since most fans don't sit very close to the stage, at least in an arena of this size, they were not privy to the disgust or exhaustion shown on the band's faces. And none of that was really known or made public until the infamous Montreal concert on July 6 when Waters lost all of his self-control and took out his frustrations on one particular fan.